ver six years ago, we surveyed providers in University of Utah’s Community Physicians Group (CPG) to understand how well we were meeting patients’ behavioral health needs. It became apparent that behavioral health needs were not being met. Since Utah has unusually high rates of depression and suicide, those unmet needs loomed large.

A too-common scenario looked something like this: A patient with depression and anxiety comes in for a visit. During that visit, he reveals suicidal thoughts. It isn’t safe to send the patient home, but there were few options available to a provider. First, the provider could tell the patient to go to the ER. If he said no, or didn't have someone to drive him, the provider could call the police to come and get him. Second, the provider could call Utah’s Huntsman Mental Health Institute (HMHI; formerly University Neuropsychiatric Institute, or UNI) for a crisis team to come talk to the patient. Lastly, the provider could call someone on the phone to try to get more advice.

All of these options are stressful and take time away from other patients. And those are the options for a patient who has insurance. Patients without acute issues, but with significant mental health needs and no insurance, money or time, can wait months for a referral.

We decided to partner with the School of Social Work and the Huntsman Mental Health Institute to pilot a program to meet our patients’ and providers’ needs. We started with four social workers in our largest clinics. Today, we have at least one social worker in every one of our community clinics. Providers are less stressed, and our patients are more likely to receive treatment for their behavioral health needs. Here’s how we did it.

Learn More

Learn more about how this group of primary care leaders fully integrated behavioral health into their practice.

"Integrated behavioral health in a clinical primary care setting"

by Daryl Huggard

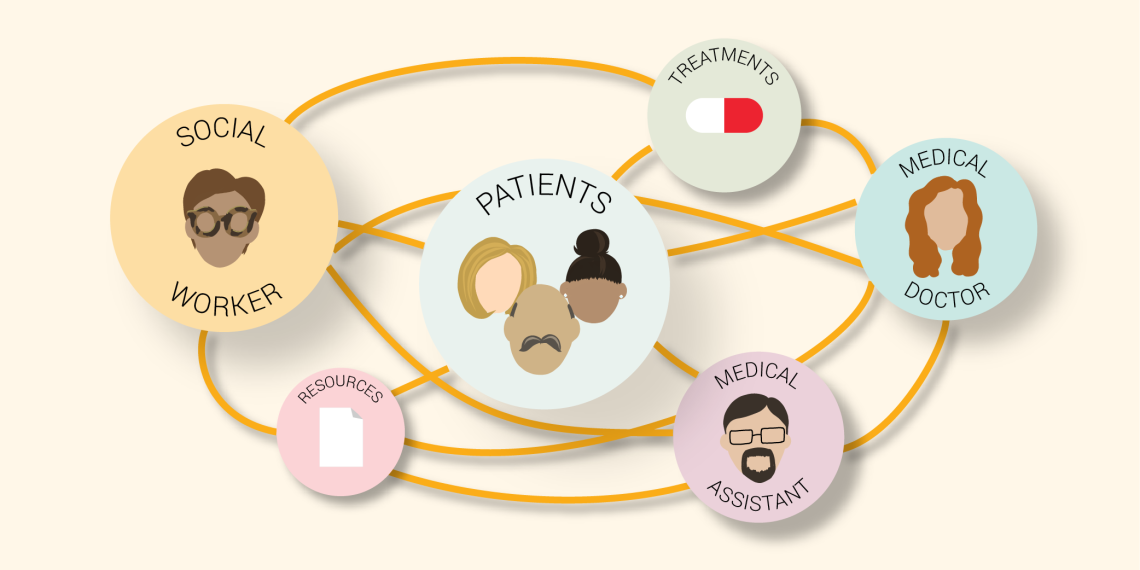

How mental health integration works

Each system, even each clinic in a system, is different. We knew from the beginning that we would not be able to import a program from elsewhere. We would need to design something responsive and unique to Utah’s needs.

Our initial analysis revealed a mix of needs. For example, clinics needed people available for crisis situations as well as continuous therapy. Medicines alone won’t solve every problem, and a lot of people prefer to make lifestyle changes rather than take medication.

Outside of traditional behavioral health needs, providers needed help managing the symptoms of mental health that impacted physical health. For example, we often will see a patient who is not managing her diabetes well because she is depressed. We introduced a model called the warm handoff for these precise situations. The medical provider can request that a social worker meet with the patient. The social worker first gets a briefing before meeting the patient to either schedule a future session or deliver immediate help in the event of a crisis. Social workers help resolve the condition or bridge them to another treatment that's more appropriate.

In addition to immediate care needs, we explored different modalities for helping patients and providers. For example, we follow up on admissions to the hospital because of alcohol use, and then connect those patients with a treatment program, resources, and group classes. We piloted a depression group class for teens at South Jordan Health Center. Even though their depression scores didn't all drop, the anxiety scores declined. Teens reported feeling more able to speak with their parents.

We’ve also acted as support for staff, especially during COVID-19. We've had scary situations in the clinic. After those moments, the social worker can say, "I'm here, if anyone needs to talk." The social worker at Westridge regularly meets with all of the medical assistants to address stress.

Training the next generation of social workers

The skills needed to practice as a social worker integrated within a medical team are not taught in most social work programs. When we hire social workers, we help them understand that our approach is a different way to practice. Not only do we practice every piece of social work—crisis, psychotherapy—we also work within the medical system. Since we practice differently, we’re continuously building our program by including the entire team as we strive to improve.

One way we are working to improve is by instituting work groups that have helped the program thrive, both for peer support and to help the program develop. We have a variety of work groups led by four different social workers. Leaders are elected by the team to contribute a quarter of their time to specific program development projects, giving them professional experience in health care leadership. We also have a strategy meeting once a week where we make decisions as a group. This approach is grounded in feminist multicultural leadership, where we deliberately model and share in decision-making and transparency.

How to hire for flexibility

It may seem awkward at first, but stepping out of the box in an interview is one of the few ways to know if a candidate is also willing to step out of the box. Try some of these unconventional interview methods and questions to hire for flexibility.

-

Have everyone sit down and then say, "Well, wait a second, this wasn't the seating arrangement, you need to..." Watch for facial expressions to see how accommodating a candidate is.

-

"If you were to walk into a room and a song was going to play, what song would that be?" How does a candidate react?

-

Good humor is essential to health care right now and can help you understand how rigid someone is. Is the candidate open to laughing, even in an interview?

Sharing a vision across departments, areas, and roles

While CPG is a primary care group and Huntsman Mental Health Institute (HMHI) is a separate location, we don't really think of each other as different teams. We are united in what we want and how we can support behavioral health integration. Each of our social workers are HMHI employees, so we have the backing of HMHI. And the program is supported with resources through the Community Physicians Group.

We couldn't do it alone. We have relied on experts and have been able to draw on their experience. Those relationships have been crucial to pushing this program forward. It has moved more quickly because of HMHI’s expertise.

More Resources

Click here to download:

ECHO COVID-19

Emotional Health during Coronavirus and Community Unrest: Tools for Providers, Families, and Patients

Click here to download: Behavioral Health Integration Services flyer

Not just for patients, but for providers too

Having social workers embedded in our practice has become a recruitment tool for providers. Primary care physicians report more burnout than other specialties, often because they feel their system’s values don’t match their own. Having mental health embedded in a practice helps a provider feel supported.

During an interview with a new provider at Westridge, a physician said, "Before our social work program, I dreaded having someone come in a crisis because it took so much time and emotional energy,” the provider said. “It was so stressful for my day that I just hoped I wouldn't have one of those patients. Now, I don't worry about it. I know who to call. I know how to get help."

That sort of resounding testimonial is possible because our social workers have helped us form closer alliances and partnerships with the psychiatry community at the U. We have more help so that we get a deeper assessment of what our patients are saying and how we can help them.

We’ve now treated over 100,000 patients. While we don't know the direct impact we've had on those individuals, whether it be stopping a suicide or helping somebody deal with chronic mental issues, we know we are making a difference. We are helping people live their healthiest life. And that's what this is all about.

Crystal Armstrong

Daryl Huggard

Teresa Lopez

When a medical error occurs, every provider needs to know how to share this information with patients and families. Timely and clear disclosure builds trust and reduces the risk of litigation. Follow this practical strategy to guide your conversation, provided by an interdisciplinary team of providers and risk managers.

Being new is hard. Often for new faculty, it means adjusting to a new state, new team, new patients, and a new organizational culture. We asked hospitalists Ryan Murphy and Valerie Vaughn and surgeon Ellen Morrow for tips that only come from a little time under the belt.

Learners, patients, and teachers are more confident and inspired when we take time to create positive learning environments. Pediatric endocrinologist Kathleen Timme gives practical advice for integrating key aspects of a positive learning environment into your daily interactions.