Learning Objectives:

After reading this article, you will be able to:

(1) identify harm and the potential for harm in a health care setting.

(2) recognize events that should be reported.

Download Slides: PPT

Case Study

Mr. Adams looked up when he heard his name called in the waiting room. His lower back pain was so bad that he’d missed two days of work. As he was ushered to the exam room by the medical assistant, he commented, "You might want to do something about those chairs in the waiting room. They're a little unsteady." The medical assistant replied, "Yes, we've heard that," and then ushered Mr. Adams to the exam room without a second thought. What happened here?

What should I report?

At University of Utah Health, we tell our employees to “report anything that harms or has the potential to harm.” This may include incidents, adverse events, near misses, or unsafe conditions. But what do these terms mean?

By the numbers

4.65 injuries per 100 hospitalizations

10-12% of patients experience harm

Approx. half of events are preventable

Harm in medical care

Harm and the potential for harm from medical care is pervasive and well-documented. Much of the safety literature has historically focused on physical harm, but the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) currently defines harm as: Physical or psychological injury, inconvenience, monetary loss, and/or social impact suffered by a person.

Some harm may be the result of medical error (and therefore preventable), while some will be an inevitable consequence of medical care (nonpreventable). Recognizing harm once it occurs is usually straightforward. To create a safer environment, individuals must also focus on instances where potential for harm exists, regardless of reason or outcome.

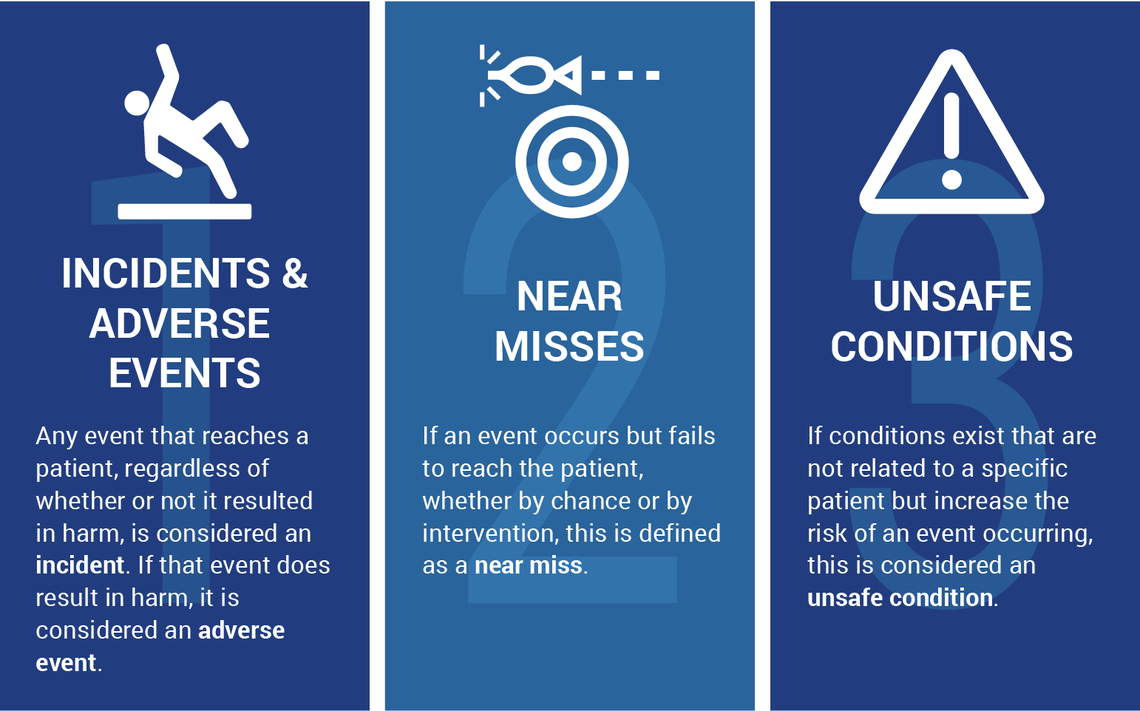

AHRQ identifies three scenarios of concern, all of which should be reported:

1. Incidents & adverse events:

Any event that reaches a patient, regardless of whether or not it resulted in harm, is considered an incident. If that event does result in harm, it is considered an adverse event.

Imagine a hospital provider accidentally prescribes a medication meant for patient A to patient B. Once the drug reaches patient B, it is considered an incident. If patient B takes the drug and suffers some form of harm, this is considered an adverse event.

2. Near misses:

If an event occurs but fails to reach the patient, whether by chance or by intervention, this is defined as a near miss.

Imagine a provider calls in a prescription to a pharmacy for an antibiotic to which a patient is allergic. If the pharmacist identifies the allergy and notifies the ordering provider to change the prescription to an alternative, this would be an example of a near miss.

3. Unsafe conditions:

If conditions exist that are not related to a specific patient but increase the risk of an event occurring, this is considered an unsafe condition.

The unsteady chairs in our introductory case study represent an example of an unsafe condition—faulty equipment is something you may find in nearly every care setting. Another example, medications with similar sounding names and labels stored next to each other, also present an increased risk of harm occurring.

What happens when I submit a report?

Every organization has a method to report safety events. As the only academic medical center in the intermountain west, U of U Health trainees often become familiar with multiple reporting systems:

For U of U Health event reporting:

Patient safety event reports filed in RL are sent to a file manager, who is responsible for review of events for a specific unit or service. This file manager investigates and takes appropriate actions, documenting the results of the investigation and following up with the frontline reporter at the discretion of the file manager. Further details on each step of the Event Response Algorithm and other policy guidelines can be found here.

For VAMC event reporting:

All event reports submitted at the VA are reviewed by the Patient Safety office, which works with the specific clinical area to help address system-based errors. Additionally, the Patient Safety office aggregates errors to detect any major trends, reporting directly to the facility leadership any recommendations for improvement.

Conclusion

The unsteady chairs in our introductory case study represent an example of an unsafe condition. The medical assistant didn’t just walk away after Mr. Adams' comment—she reported it. This simple act helped to prevent future harm. Whether you identify an incident or unsafe condition, experience a near miss, or witness an adverse event, each represents harm or the potential for harm. Each should be reported using your organization’s event reporting system.

References and Resources

- Patient Safety Primer: Adverse events, Near Misses, and Errors (AHRQ | 3 minutes) A nice history lesson and study overview with concise definitions.

- U of U Health, on Pulse: More on what to report from the patient safety department.

- U of U Health: Click here to report a patient safety event in RL (Utah’s event reporting system)

This article was originally published June 2018.

Ryan Murphy

The practice of medicine is recognized as a high-risk, error-prone environment. Anesthesiologist Candice Morrissey and internist and hospitalist Peter Yarbrough help us understand the importance of building a supportive, no-blame culture of safety.

Is zero possible? In the case of central line infections, the answer was once no. A CLABSI (central line associated blood stream infection) was once considered a car crash, or an expected inevitability of care. When University of Utah’s Burn Trauma Intensive Care Unit started treating CLABSIs like a plane crash, or a tragedy demanding in-depth investigation and cultural change, zero became possible.

The Zero Suicide initiative has been shown to significantly reduce suicides—and working toward zero suicides is our mission. Rachael Jasperson, Zero Suicide program manager, shares the framework for how we strive for this aspirational goal.