The Challenge

ess than a decade ago, CLABSIs were considered the most pervasive of all hospital-associated illnesses (HAIs). Across the United States, 500,000 patients contracted a CLABSI between 1990-2010—an average of 25,000 per year.

A single CLABSI incident can exact a long-term toll on patients, setting off a cycle of weakened immune system, infection, and possibly septic shock.

CLABSIs’ endemic nature made the path to prevention seem impossibly complex. In 2011, the Center for Disease Control issued an 80-page document listing various techniques to prevent central line infections. Without standardization and simplification, such recommendations were difficult to implement.

To eliminiate infections, a strong team focused on psychological safety and standardized processes was needed. Could the Burn Trauma Intensive Care Unit (BTICU) change their culture to prevent CLABSIs? Could nurses and physicians change the way they worked together inserting, maintaining, and removing lines?

Background

I. A plane crash or a car crash?

The BTICU is the only burn center in a 400-mile radius and admits 300-350 children and adults each year. In 2011, a Vizient (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium) study identified the unit within U of U Health with the highest CLABSI rate: the BTICU. Infection Prevention Clinical Operations Manager Cathy Gray teamed up with BTICU Nurse Manager Brad Wiggins, Clinical Nurse Coordinators Lois Remington and Colby Carper, Nurse Educator Kristy Gauthier, and surgeon Amalia Cochran to find out why.

Central line catheters are placed intravenously in the neck, groin, or arm to deliver medication and allow needle-less blood draws. The longer a central line remains, the higher the risk of infection. BTICU patients carry even higher risk due to extended hospital stays, open wounds, frequent dressing changes, and significant fluid management needs.

It’s called a critical care unit for good reason: “A patient might die if they don’t get their medication in the next 30 seconds,” Brad Wiggins says. “The environment lends itself to frequent or excessive lines, and before this quality improvement project, those lines were often placed or removed by physicians in a hurry, without following all the procedures.”

Wiggins describes the car crash mentality: “Nurses weren’t empowered to speak up if they saw something unusual. And if a patient got an infection, we often said, ‘It happens. It’s pretty normal.’”

The team set out to study this like a plane crash: considering CLABSIs a preventable error, not a normal side effect. “We saw our numbers and said, ‘We’re not okay with this,’” Cochran says. “‘Our patients deserve better than this.’” The team believed zero was possible. A goal that once felt audacious—impossible even—could be achieved.

The Plan

II. Let's get better together

The team (Wiggins, Remington, Carper, Gauthier, Cochran, and Gray) set out to:

- Identify the protocol for central line insertion, maintenance, and removal

- Document each step of the sterile process and any point of potentially increased risk

- Develop a standardized checklist for insertion (Download Word document)

- Decide who was responsible for following the checklist and holding team members accountable

- Determine how to better monitor infections in accordance with hospital and industry regulations

The BTICU’s team had a built-in advantage. Wiggins described their controlled environment: a small, stable group of physicians (Drs. Steve Morris, Amalia Cochran, and Giavonni Lewis) with a consistent nurse management team caring for a specialized and similarly diagnosed patient population under centralized observation.

An attitude of “Let’s get better together” permeated the BTICU. “That’s a learned skill in the ICU environment,” Wiggins says. “Physicians at a level one academic research institution like Utah should allow nurses to voice their opinion — and nurses should be encouraged to speak up and advocate for their patients. That culture is something we’ve created as a team.”

Colby Carper adds, “The biggest factor was sitting as a collaborative group, looking at the problem, and identifying markers that needed improvement.”

III. The multi-pronged "CLABSI bundle"

The team identified numerous small opportunities to avoid infections.

First, nurses and doctors opened their practices to observation. Specific insertion, maintenance, and removal steps were identified to create a central-line insertion checklist.

Working with Cochran, the nurse leaders finalized the new checklist for central line insertion, presenting it to the Burn Unit’s three physicians, who elected to participate in further auditing, evaluating, and teaching. The point was to make everyone aware of how they could contribute to the CLABSI rate reduction project. “Every time you touch that patient, there’s an opportunity to prevent an infection,” Gray says. “If you take that opportunity and give it the same attention and dedication every time, you can get to zero.”

“Every time you touch that patient, there’s an opportunity to prevent an infection,” Gray says. “If you take that opportunity and give it the same attention and dedication every time, you can get to zero.”

The team wanted the right products to help them prevent infection. After investigation of multiple options, the team decided on an anti-microbial catheter line and Curos alcohol-impregnated caps.

Extensive bedside audits led by Carper and Remington ensued, earning them the nicknames “CLABSI Police” and “Curos Cops.” They asked nurses to document central line dressing changes and provide detailed wound evaluations.

They asked physicians and nurses to change the way they charted. If, after daily review, nurses or physicians elected to leave a line in, an indication for it had to be documented.

“That was so important for nursing culture,” Carper says. “Nurses were reminded daily that their role was important. We chased those intricate things for months until we finally got to where we didn’t have to point them out as much.”

The team created what they called the “CLASBI bundle”:

- Anti-microbial catheter lines and alcohol-impregnated caps

- Central line insertion checklist

- Rounding checklist to review the necessity of all invasive lines

- RN assessment of line positioning

- Time-out before line is inserted or removed

IV. A culture of psychological safety

Beyond these specific steps, a cultural shift toward psychological safety began to take place on the BTICU, with Cochran, Morris, and Lewis comfortable being challenged. “We preach a message of, ‘If you think you know better, you don’t,’” Wiggins affirms. “It’s not hierarchical here. Our physicians bought in to the process from the beginning to make sure that each patient was kept as safe as possible.”

Cochran says that open communication is not assumed in critical care units—particularly in the surgery world. “There were nurses for whom this was a paradigm shift,” she says. “It was important that they learned to use their voices, and equally important that we, as physicians let them know that we really value their role as patient advocates. The surgeons are captains of the ship, but creating a space for everyone’s voice to be heard allows our patients to receive the very best care they can.”

Prior to this project, Carper says nurses uniformly relied on the physician to decide when a central line was needed. Now, they are empowered to claim ownership of that decision.

The central line checklist became the primary reference point. It resides in a file at the nurses’ station and also at the bedside in every room, and nurses are empowered to retrieve it, follow it, and alert physicians to any mistakes or shortcomings. “If a nurse saw something inappropriate while a central line was being inserted, they could hold the physician accountable and stop the process,” Carper says. Or, as Cochran says, “It’s the little things that are actually the big things.”

Ongoing mentorship and training continues for nurses and clinical staff, with tools and resources available to reinforce the Burn Unit’s collaborative culture. Critical thinking is welcomed and rewarded; opportunities for further quality improvement are encouraged; and results are examined carefully. “Dialogue happens here; egos are set aside,” Wiggins says. “That’s our culture.”

All of this work allowed the Burn Unit to embed these ideas into unit culture, hardwiring the improvement into their everyday process. “It’s okay to talk about what you did wrong here,” Wiggins says. “It’s okay to come up with a game plan to resolve those issues. You have to work together as a team and not be afraid to change your practice.”

Metrics

V. Measuring Success

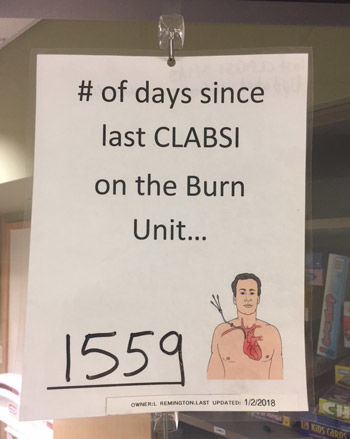

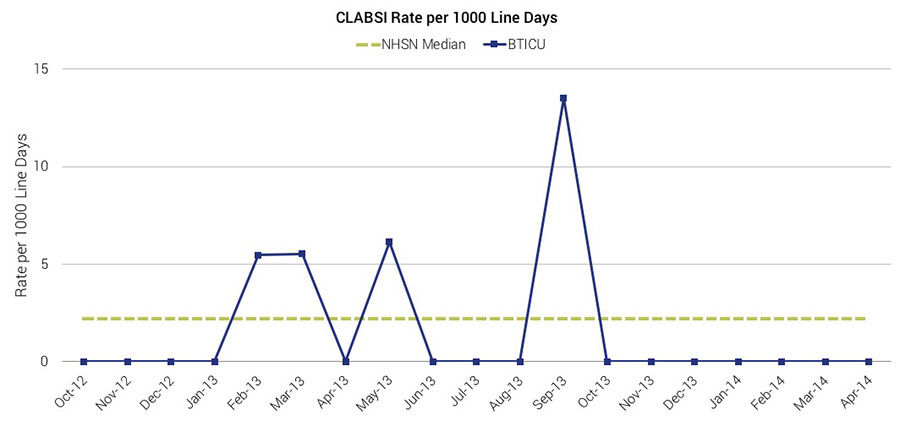

After several spikes and dips between October 2012 and September 2013, when 14 CLASBIs per 1,000 line days were recorded, the Burn Unit’s infection rate fell to zero in October 2013—and has remained there ever since.

Once the team got to zero, the hard work truly began: sustaining the improvement to meet both Utah’s value equation and stringent American Burn Association requirements that require units to focus on, measure, record, and improve quality.

The team emphasizes the fact that they’ve had several close calls over the last four years, and they know that the possibility of a central line infection always looms. Wound documentation according to NHSN guidelines is key, Remington says. “I educate our nurses about the importance of being clear and concise in the documentation of a wound. That way, if we do suspect that we meet the criteria for a central line infection but it turns out to stem from a prior wound issue, we can prove what came first.”

Reflection

VI. "Zero is possible"

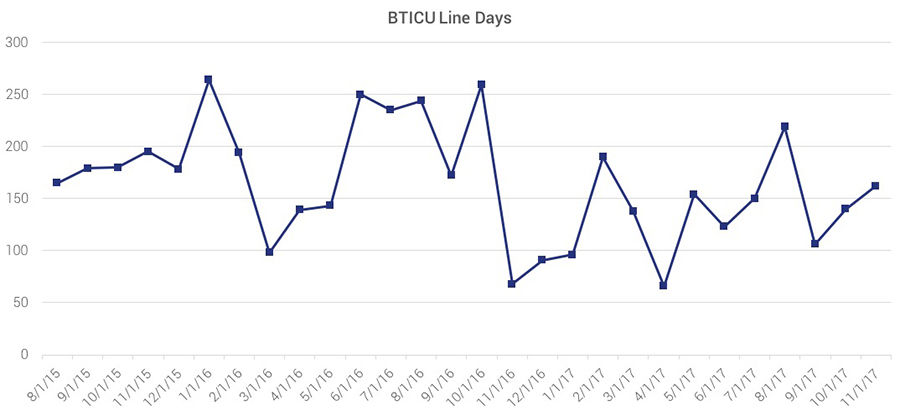

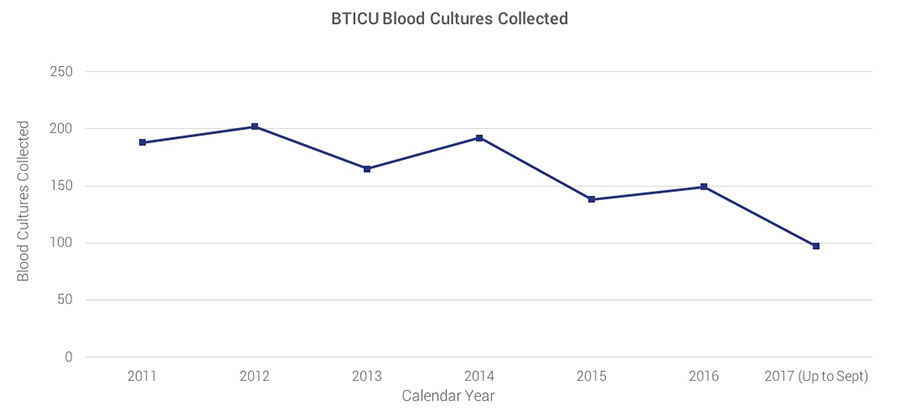

Everyone on the team emphasizes the fact that the change is real: BTICU line days are still high, indicating that the acuity level of its patients has not decreased, while staff is still culturing patients at a steady rate. “We’re not hiding the data or gaming the system,” Cochran says. “If you had told me four years ago we’d be having this conversation, I would have laughed and said you’re crazy. I thought there was no way zero could happen on the Burn Unit.”

As Gray says, infection rates are not just numbers we report to the CDC. “We use infection stories in our educational program for nurses. It’s about drilling down to the individual patient level instead of just looking at the system so it’s clear how one single infection can have a significant impact on a patient.”

Cochran reinforces that message. “Working as a team isn’t just something that makes us feel good. This project enacted a cultural change. We’re helping our patients avoid complications that are completely preventable. That changes the way our patients and their families experience care.”

Everyone involved emphasizes the fact that the success of this project stems directly from the BTICU’s culture. “They’re the only unit that uses a checklist for every line insertion—and they don’t have any central line infections,” Gray says. “Everyone in the hospital knows that. It’s not a suggestion or a nice to-do. It’s not a top-down mandate. It came from the staff. It’s an expectation.”

“Working as a team isn’t just something that makes us feel good. This project enacted a cultural change. We’re helping our patients avoid complications that are completely preventable. That changes the way our patients and their families experience care.”

The Value Equation of preventing a central line infection

Central line infections result in thousands of deaths and billions of dollars of added cost. The lack of central line infections improves patient and family experience by reducing the length of stay.

Value = Quality + Service/Cost.

After two years without CLASBIs, Gray and her Infection Prevention team began teaching other University of Utah Hospital critical care units about the BTICU’s process. But the success is not perfect; the BTICU is currently struggling with a spike in catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), leading the staff to use the same value improvement methodology to combat a new infection problem.

The BTICU illustrated how to treat central line infections as plane crashes instead of car crashes, compiling a team to investigate its mistakes and make meaningful change that ultimately leads to success. “On the Burn Unit, we get better from our mistakes every day,” Wiggins says. “As Nurse Manager, that’s my focus. Maybe I push too hard on it, but if you expect to make a mistake, you’ll figure out how to fix it.”

“People used to say, ‘Well, it’s health care — infections happen,’” Cathy Gray finishes. “But they don’t have to. With consistency and culture, you can do anything. Change is possible. Zero is possible.”

Think this might work for you? If so, Brad Wiggins' SlideShare will be helpful.

Header image of Burn Trauma ICU Team (Front row, from left): Dr. Gia Lewis, Dr. Stephen Morris, Dr. Amalia Cochran; (Second row, from left): Xavier Lucio, Jill Clark, Lisa McMurtry, Keri Simonson, Annette Matherly, Halle Kogan, [not identified], Caran Graves, Chelsea Gamero, Bret King, Emily Ferrero, Colby Carper, Cindy Lundy; (Row three, from left:) Monica West Ann Cook, [not identified], Bri Hendricks, Crystal Webb, Ronda Hopkins, Lee Moss, Kristen Quinn, Carlyn Meeks, [not identified], [not identified], Natalie Murphy; (Row four, from left): Sean Hepner, [not identified], Lacy Arnold, Kristy Gauthier, Kassie Olsen, Jill Leo, Scott Price, Sue Jardine, Whitney Mason, Daniel Knitz, Maureen, Brad Wiggins.

Nick McGregor

Mari Ransco

Steve Johnson

Amalia Cochran

Cathy Gray

Brad Wiggins

Internal medicine residents Brian Sanders and Matt Christensen team up with senior value engineer Luca Boi to explain why investing your time honing a well-defined problem statement can pay dividends later in the ultimate success of a QI project.

A step-by-step discussion of the 7 elements of suicide care.

Many people ask, “What am I supposed to report?” or “Does this count?” Hospitalist Ryan Murphy explains the basic vocabulary of patient safety event reporting, informing the way we recognize harm and identify and report threats to safety.