or 30 years, the thrill of working high-risk jobs like labor and delivery has appealed to my inner adrenaline junkie. Like me, many health care workers thrive in these fast-paced, rewarding careers. Stress and trauma become almost second nature to us, and we learn to push past our fear and spring into action. But since the outbreak of COVID-19 and increased social upheaval, we’ve seen employees’ stress and trauma levels skyrocket.

In our current state of unrest, employees have grown distracted and we’ve seen a spike in medical mistakes, even for simple procedures. As stress levels rise, our workers’ confidence plummets.

Even though we aren’t experiencing our patient’s own health issues, we’re still experiencing secondary trauma. It’s not ours; we don’t own it. I’m not ill or losing a loved one, but I’m witnessing it every day. While we fight to help our patients survive and recover, our work culture doesn’t give us time to treat our own trauma.

Primitive brain vs. executive brain

So what is triggering these elevated levels of secondary trauma in employees? High-pressure situations, like COVID-19, force us to rely on our primitive brain for guidance. While our emotions are complex and unpredictable, decreasing stress can actually be quite simple. First, we must differentiate between our primitive and executive brains.

The primitive brain is comprised of our survival instincts. It triggers our fight-or-flight responses, our gut reactions, and we often rely on these primitive instincts in emergency situations. While rapid responses can be crucial in health care, split-second decisions can overpower our critical thinking, or our executive brain.

Our executive brain regulates our decision-making and reasoning skills. We use our executive brain to help us make safer, more compassionate choices.

The unpredictable nature of COVID-19 has caused health care workers to fall back on primitive reactions and has piled even more pressure onto a job that’s already at full capacity. Unchecked stress can lead to brain burn, or compassion fatigue. We need to combat burnout by creating a space for employees to learn how to process their anger, fear, and frustration.

The technique: MindShield

If we want to stay relevant as a hospital, our employees must learn how to respond to stressful situations better. MindShield, developed by U of U faculty Rich Lanward (Social Work), Caren Frost and Lisa Gren (Family and Preventive Medicine), was initially introduced as a tool for firefighters to reduce trauma and anxiety. It has been highly effective in health care as well. This simple training exercise combines basic breathing techniques and critical-thinking in order to help us access our executive brain.

How to map your stress

-

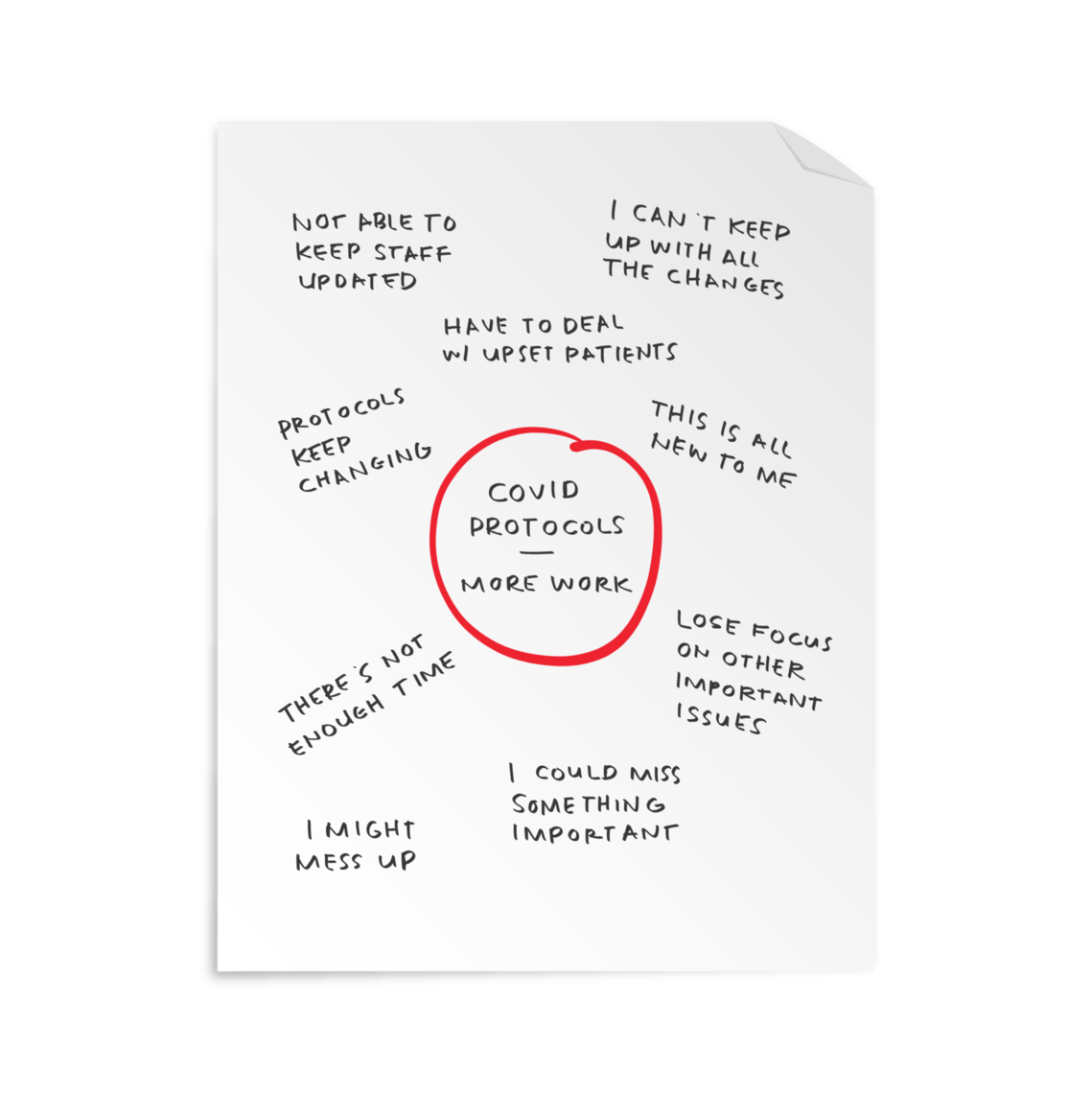

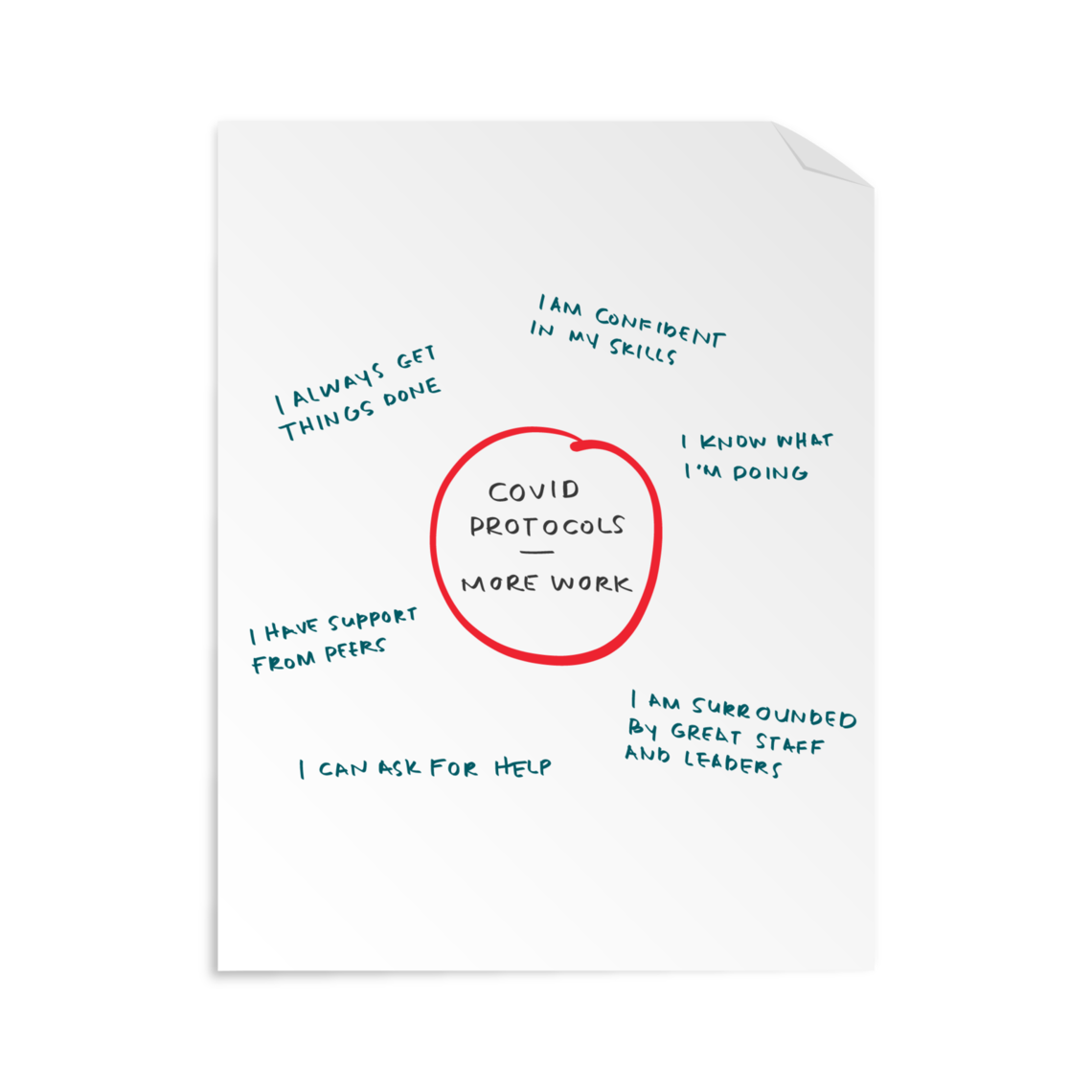

Step 1: Take a piece of paper and draw a circle in the center. In that circle, write down an incident that is causing you stress.

-

Step 2: Write your thoughts and concerns in the space around the circle.

-

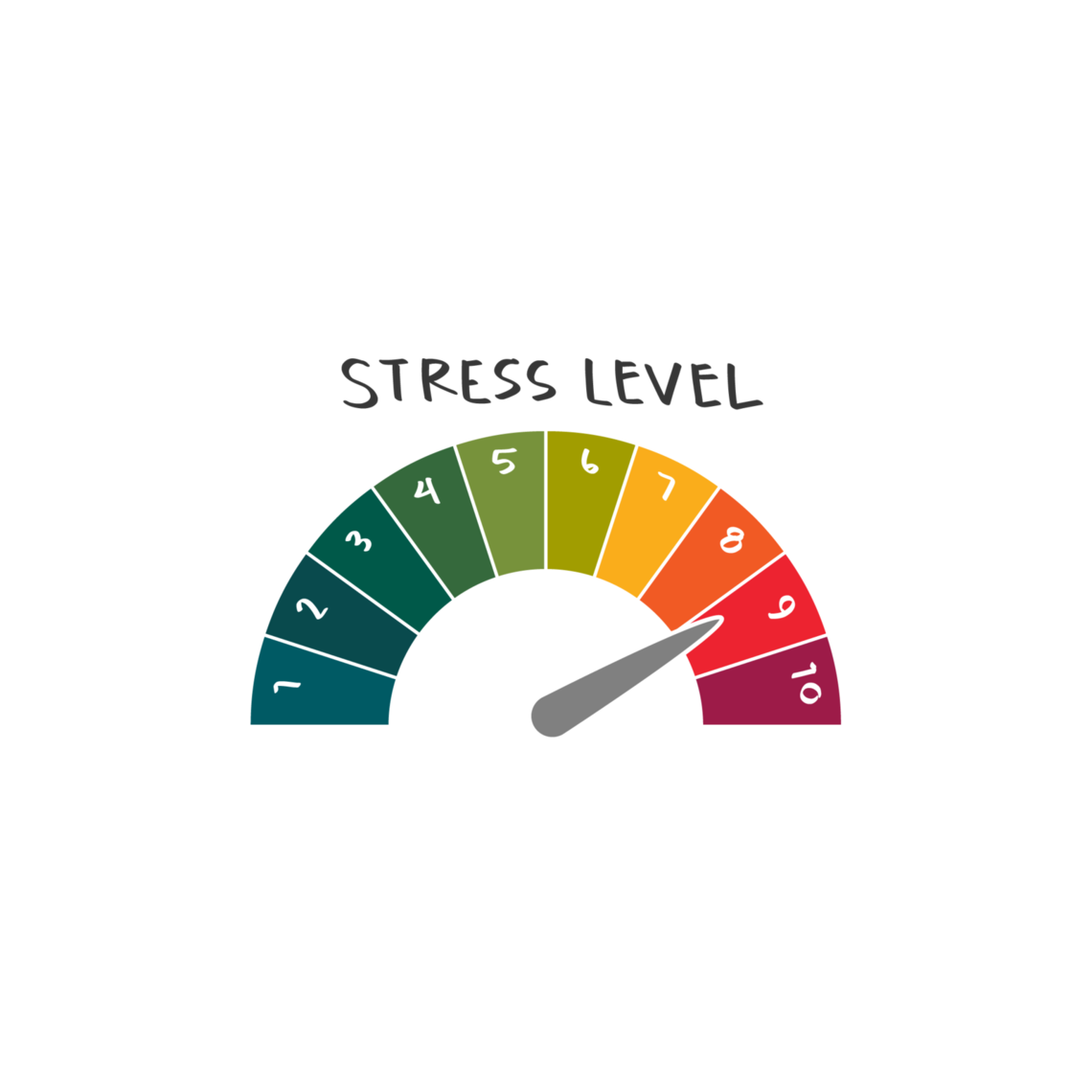

Step 3: Mentally connect with your body and ask yourself the following questions: How high is my stress, on a scale of 1-10? Where am I feeling the stress in my body?

-

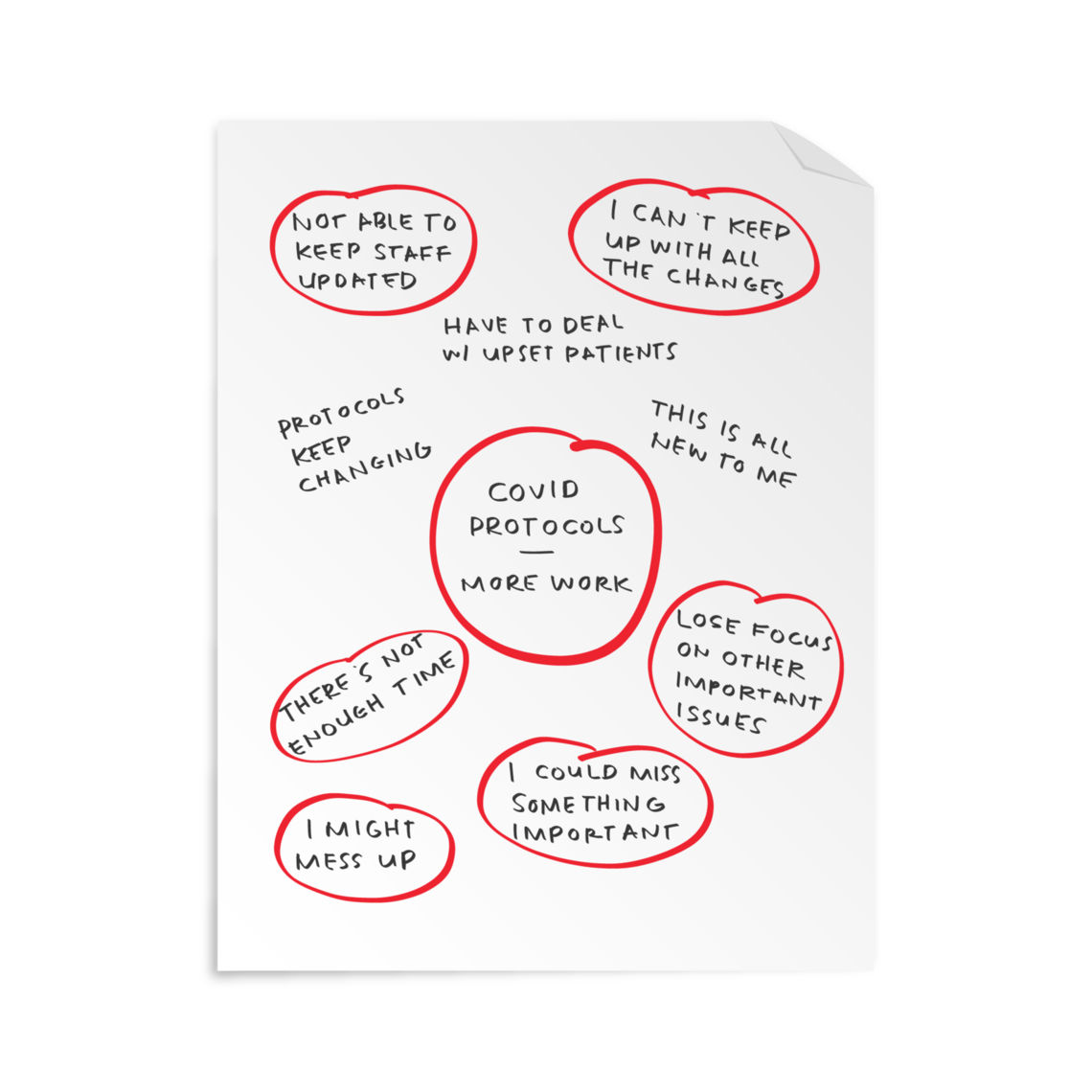

Step 4: Look at your map and circle any unmet expectations (something that didn’t happen that you expected to happen) or storylines (something you’re telling yourself that may or may not be true). Acknowledge and validate these worries.

-

Step 5: Pick a source (a person, place or thing that brings you peace). Focus on your source and take 3 deep breaths.

-

Step 6: Flip your page over, draw another circle, and write the same incident in the center.

-

Step 7: Again, scatter your thoughts around the circle. This time, you’ll find that your executive brain has taken command. Your thoughts will focus on elements you can control, rather than the things you cannot.

-

Step 8: Reconnect with your source and reevaluate the level and location of your stress. It should live in a different place.

View an example of the technique below:

Conclusion

Incorporating this process into your daily work isn’t about eliminating your primitive brain. It’s about finding a balance between your primitive and executive instincts when stress inevitably does kick in. We’re all feeling the multiple sustained traumas of COVID-19 and social unrest. This simple practice can help us all react in more positive ways.

Bernice Tenort

We’re all managing unprecedented stress and fear. What is “normal” right now? How do I cope? Social worker Jean Whitlock describes how our body protects us and offers some strategies to help.

There may be light at the end of the pandemic tunnel, but that doesn’t mean the stressful days are behind us. Jean Whitlock, of the Resiliency Center, shares how you and your teams can assess your stress levels and identify ways to manage them.

Nurses are notorious for not taking breaks—the culture of their work environment doesn’t make it easy. Katrina Emery, a MICU charge nurse working on her doctor of nursing practice (DNP), sheds light on how to change culture to prioritize breaks to improve health and wellbeing.