very day in the medical intensive care unit (MICU) we see very sick and complex patients that we can’t easily fix or heal. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the 80 nurses on the MICU deal with the very sickest of those patients. There are typically 12 to 16 nurses working during each 12-hour shift. These are long days, caring for our patients and fellow nurses between donning and doffing powered air purifying respirators and other essential PPE.

When my shift ends and I walk to my car, I try to decompress. I think back on my day and often worry if I have helped enough. Sometimes, it's hard to comprehend all that happened during my shift. Other days, I feel I was a good nurse and that I helped everyone, including my patients and coworkers.

Helping nurses help each other

I began the “Restorative Break Initiative” to help nurses get the breaks they deserve. Helping each other is part of our nursing culture. That’s why as part of a requirement to receive my doctor of nursing practice, I wanted to complete a project that would help nurses build resiliency and avoid burnout.

My typical day as a RN in MICU:

6:45 am: Arrive at work and change into scrubs. Put on my surgical mask and find my powered air purifying respirator (PAPR) hood.

7:00 am: Begin my shift with my morning meeting and receive my patient assignments, typically 2 patients.

7:15 am: Get a report on my patients from an off-going nurse, including their name, age, code status and current condition, as well as any important events that happened the night before.

7:45 am – 5 pm: Caring for my patients, including giving medication, coordinating care with nursing assistants, therapy, and other services. Depending on the complexity of their care, I may be at the patients bedside for 10 minutes to an hour (or longer) at a time. Throughout the day, I also chart about their care, report information to the providers and get my patients to any testing they need.

Throughout the day nurses also help each other out whenever possible. If my patients are stable, I may help a nurse who has a more complex patient. It’s part of our culture to support each other.

5:00 pm: Begin planning for the night shift, reporting to the charge nurse about our patients.

7:00 pm: Evening meeting to discuss patients.

7:15-7:45 pm: Give report to the oncoming nurse.

7:45 pm: Clean and sanitize PAPR hood, glasses, pens, stethoscope, ID badge, etc. Change into my street clothes, wash my hands and leave.

When I started exploring project ideas, a colleague mentioned to me that nurses don’t take their breaks. It was like a lightbulb went off. She was right; many nurses weren’t taking their breaks, including me. We all felt the pressure of getting all of our tasks done. We felt the weight of responsibility in caring for our patients.

As I told more people about my project, more colleagues agreed that nurses don’t take breaks. The data supports this trend—35 percent of nurses report rarely or never taking a break.1 A similar number, 25 to 33 percent, of ICU nurses experience burnout syndrome each year, causing them to leave the nursing profession.2,3,4

I wanted the nurses themselves to change nursing culture and make breaks a habit.

Here’s what I did:

Shifting culture slowly but surely

Start with the literature. I researched resiliency and nursing. There wasn’t a lot of information in the literature about breaks specifically. Nurses are known for caring for other people; they aren’t known for caring for themselves.

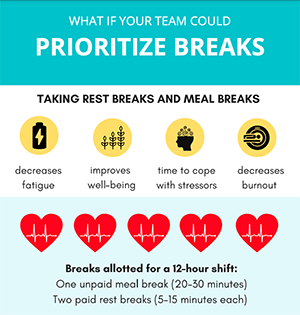

Collect data. Next, I sent out a survey to all of the nurses on the MICU, about 80 people at the time. Fifty-eight people completed the survey. The survey revealed that almost half of the nurses didn’t know the number of breaks allotted in their shift.

Build awareness. The survey made it obvious that we needed to raise awareness about breaks. During a Zoom staff meeting, we spoke about my break initiative and explained how many breaks nurses were allowed to take. Many people told me after the meeting that they had no idea they were allowed to take additional breaks. They felt guilty taking time away from their work.

We began spreading information about why breaks are important and why people should take breaks, even just 10 minutes to sit down to eat a snack. Since I was also inconsistent with taking breaks, I tried to lead by example. I took my breaks and asked my colleagues if they had taken their breaks.

We formalized our approach by breaking our unit into three pods and appointing daily pod break leaders to encourage breaks.

Influence leadership. The more people talked about it and the more people heard about the break initiative, the more likely they were to take breaks. Management also provided support by encouraging breaks and creating a 4-hour lunch shift. This shift ensures that as nurses take lunches, there are still enough people on the floor to offer care.

Create a formal campaign. While leading by example and word of mouth helped, we needed a formalized campaign to really make an impact. Colleagues from the Resiliency Center helped me realize how to make our efforts into a bigger, hospital-wide project to help nurses on every unit. Our campaign featured flyers, placed throughout nursing work areas, that provided all the information people needed to take breaks, including:

-

How many breaks nurses should take

-

How long breaks should be

-

Where nurses could take breaks

-

The benefits of taking a break

-

The steps needed to take a restful break

Prepare for resistance. Not everyone was fully on-board with the break initiative. Some shifts are understaffed or very busy. Some people are also resistant to the change. Hopefully, as the culture continues to shift, we can take steps to ensure all nurses get the breaks they need.

A ripple effect

With each new person that finds this initiative important, each nurse that begins to take breaks, each person that offers to cover a colleague’s patients while they take a break, we see a ripple effect. More and more people become involved. With time, we will ensure that all nurses receive the breaks they need and deserve.

References

1. Nejati, A., Shepley, M., & Rodiek, S. (2016). A Review of Design and Policy Interventions to Promote Nurses’ Restorative Breaks in Health Care Workplaces. Workplace Health & Safety, 64(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079915612097

2. Moss, M., Good, V. S., Gozal, D., Kleinpell, R., & Sessler, C. N. (2016). A Critical Care Societies Collaborative Statement: Burnout Syndrome in Critical Care Health-care Professionals. A Call for Action. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 194(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201604-0708ST

3. Nursing Solutions, Inc. (2020). 2020 NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report. www.nsinursingsolutions.com; Teixeira, C., Ribeiro, O., Fonseca, A. M., & Carvalho, A. S. (2013).

4. Burnout in intensive care units—a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: A descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiology, 13(1), 38–68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-13-38

Originally published February 2021

Katrina Emery

When life gets busy, it’s easy to forget what keeps us grounded and therefore more satisfied with life. Sydney Ryan reflects on the importance of making time for yourself and prioritizing what is important for you. She explains simple, deliberate actions that have made a difference in her work and her life.

There may be light at the end of the pandemic tunnel, but that doesn’t mean the stressful days are behind us. Jean Whitlock, of the Resiliency Center, shares how you and your teams can assess your stress levels and identify ways to manage them.

Family Medicine physician and co-director of the Resiliency Center Amy Locke outlines five ways U of U Health’s strategic commitment to well-being is paying off during COVID-19.