ill the US health care financing system change via a thoughtful, tactical shift in the way patients pay for care or will the system eventually break?

That question fuels much of the conversation around Medicare for All. Recent polls show that up to 70% of Americans think the us health care system is broken and needs to be fixed.

First, let’s place the obvious out in the open: the concept of Medicare for All is fraught with political tensions. This fact has been highlighted by nearly every major news outlet across the country, from the New York Times to Fox News. It comes up repeatedly in Democratic political debates, which further politicizes it.

The concept of Medicare for All (or a similar, single-payer insurance system in the United States—more on this later) should be explored in terms of the potential opportunities and challenges, outside of its political realities, good or bad.

Quick Point of Clarification

The concepts Medicare for All, single-payer, universal coverage, or socialized medicine are often conflated and used interchangeably. They can be related, but are not the same. The following definitions, paraphrased from a discussion with physician Peter Weir, executive medical director of population health, are important for context.

-

Single Payer: This could be a single government payer, or a single commercial payer. Not necessarily via Medicare. In Canada, for example, the government is the dominant payer, but they depend on private infrastructure to deliver care.

-

Universal Coverage: Single payer, either via a private company or the government, is one option. But so is expanding “safety-net” insurance (Medicare/Medicaid) and private options (the exchange) within our current system. Germany is an example of universal coverage, which also utilizes private insurance.

-

Socialized Medicine: The government is often the largest payer and can own the delivery systems (hospitals and clinics), but not necessarily. For example, in the United Kingdom the government is in charge of the payment and delivery system.

20 U of U Health leaders weigh-in

Special thanks to

- Kelsey Barrell

- Dayle Benson

- Gordon Crabtree

- Candice Crawford

- Kathy Delis

- Talmage Egan

- Samuel Finlayson

- Sandi Gulbransen

- Michael Hales

- Brita Manzo

- Robin Marcus

- Amy Mitchell

- Richard Orlandi

- Charlton Park

- Robert Pendleton

- Brian Shiozawa

- Barb Viskotchil

- Peter Weir

- Karen Wilson

- Mark Zenger

To explore the Medicare for All concept I interviewed 20 University of Utah Health leaders ranging from frontline clinic managers to the c-suite. Over the next several months I’ll be sharing their thoughts. This initial article will highlight some of the overarching concepts shared by respondents. Subsequent articles will focus on opportunities and challenges of a Medicare for All system, possible steps for implementation, and how roles across health care might shift if a this system were implemented.

Where we all agree

Something needs to change

Every interview shared a common thread: something needs to change within the financing of health care.

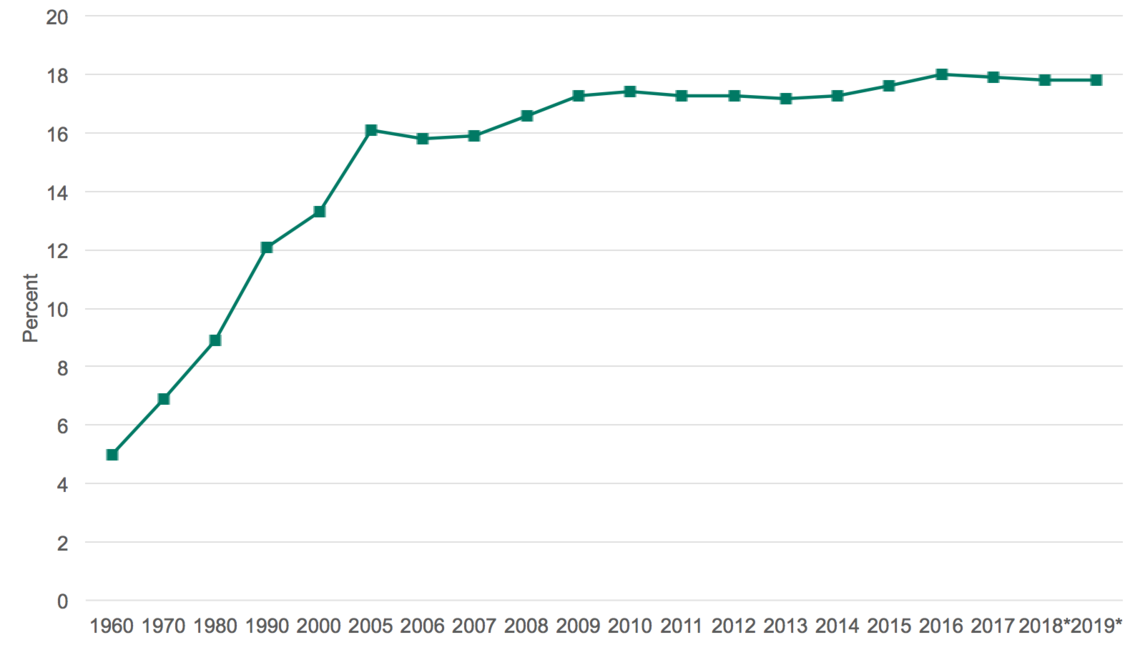

It is unsustainable when you look at the percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)GDP represents the total value of goods and services provided in a country during a given year. In 2017 that equaled nearly $20 trillion for the United States. that health care represents–specifically how that percent has increased over time.

Looking at the most drastic change, health care expenditures as a percent of the nation’s total GDP has increased 260% in the past 60 years (18% in 2017, only 5% in 1960).

While those numbers are often cited for persuasion purposes, they are misleading for one main reason—1965 was when Medicare (care for the old) and Medicaid (care for the poor and disabled) went into effect. Lyndon Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965 as part of the Great Society programs of the time, and with that Medicare and Medicaid were created to help provide medical coverage for many who previously did not have access.

Naturally, this policy change caused the overall costs of health care to expand, which was already noticeable in 1970 when health care as a percent of the GDP jumped to 6.9% (a 38% increase from the prior decade). For a more recent comparison of the costs of health care increases (as a percent of GDP) look at 2000 vs 2010. The increase from 13.3% (2000) to 17.4% (2010) indicates a 30% increase in the overall cost of health care—and it has stabilized since 2010 at around 17%Let’s think about that: Is 17% a healthy, stable number to hold onto, or is this too much for society to maintain?.

Health care for all is a noble aim—the devil is in the details

Everyone I spoke with agreed that providing health care for all is a noble aim, the issue is exactly how you go about doing that.

Some practical questions include:

-

Would a single, federal payer be the best way to achieve the goal of health care for all?

-

Aside from financing this new system, which is fraught with additional questions, how would the change from our current system take place?

-

Would this stymie or promote innovation?

-

What would happen to several large industries/groups, including the commercial payers (think United or Anthem), hospitals, clinics, physicians and their care teams, and the current health care administration teams?

A big hairy audacious challenge—are we ready?

The US health care system is a $3.5 trillion industry. Trillion.

Let that number settle in.

On average each person in the US, babies and children included, spend over $11,000 each on health care in 2018.

The five largest health care insurance companies in the United States (United, Anthem, CVS Health, Cigna, and Humana), cover 145.4 million US citizens, or roughly 44% of the population. They generated nearly $600 billion in revenue and employ about 775,000 people. And that’s only the top five, currently there are close to 900 insurance companies that offer some form of health care in the US.

The sheer scale of the current system, with interconnected companies and processes, and the powerful forces that bind the US health care system together are staggering. Though that doesn’t mean change is impossible.

The view of my respondents, as well as most industry experts, is not, “Will it change?” Rather, “What will cause the change?” And, more importantly for U of U Health leaders, what part of the change will we be?

Answering these questions will be a marathon, not a sprint.

Stay tuned.

Zac Watne

Patients will ask three things of us over the next decade of health care improvement: help me live my best life, make being a patient easier, and make care affordable. To meet those needs health care must shift—from organizing around a patient’s biology to understanding the patient’s biography.

Sometimes the most impactful change comes from simply asking, “Why are we doing things this way?” Pediatric infectious disease professor Adam Hersh explains the impact of practice inertia on antibiotic treatment in pediatric patients, and how questioning the status quo improved outcomes and reduced cost.

Utah’s Chief Medical Quality Officer Bob Pendleton describes a strategic challenge faced by many industries, including health care. We are at risk for prioritizing achievement of metrics over our purpose. He challenges us to think beyond metrics to what patients actually need from us: patient-centered, outcome-focused, affordable care.