Big Idea:

Rather than succumbing to practice inertia, we need to test new hypotheses, ensure that our practice aligns with evidence-based guidelines, learn from practices at peer organizations, and consider cost, quality, and experience outcomes to determine the best care for each individual patient.

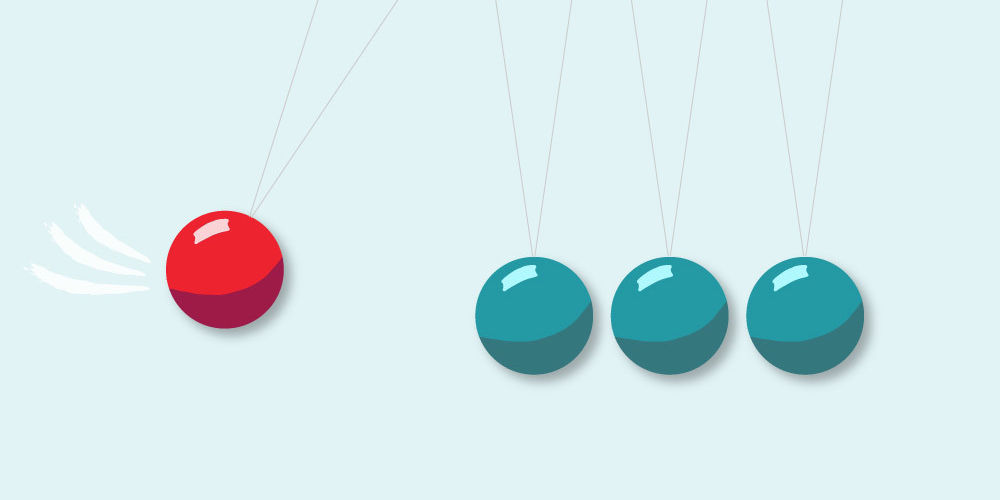

ewton’s first law of motion states that an object will remain in motion at a constant speed unless acted on by an unbalanced force. In medicine, there’s a tendency toward what is called practice inertia—where care teams continue to do something a certain way simply because they always have. As we find better ways to care for patients that are more cost-effective and provide better outcomes, it’s critical that we get in the habit of disrupting our practice inertia.

It’s always been done this way

For many serious childhood infections that initially require hospitalization, treatment is started in the hospital but is often completed at home once the child is on the mend. In many cases, the treatment period at home is equal to or even longer than the time in the hospital. Some of the common infections we treat after hospitalization include bone and joint infections, pneumonia, bloodstream infections and meningitis.

We have had practice inertia around how to most safely and effectively treat a variety of these infections. There has been a prevailing belief that the best way to complete therapy after hospitalization was to use intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy at home.

This is for a couple of reasons. First, most of the time IV therapy works really well and our patients get better. Second, we have long believed that for serious infections, more antibiotic was better. We felt that we always needed to deliver the maximum amount of antibiotic possible to the site of infection (e.g. an infected bone). The IV route does this better than the oral route because the medication is delivered directly into the bloodstream rather than having to be absorbed through the stomach.

But, even if IV therapy was usually superior (turns out it’s not) it comes with extra consequences compared to oral therapy. It requires placement of and use of a central catheter to administer the medication which is expensive, comes with risks including infection of the catheter itself, dislodgement which may require replacement and the development of potentially dangerous clots.

Administering IV antibiotics at home involves a substantial burden on caregivers who themselves must learn some basic nursing skills in order to administer IV medications for their child. Because the view was so strong that IV was better, the impact of these added risks and burden may have been somewhat underappreciated by doctors in our field.

"It was becoming evident that we might have become victims of our own experience. Compared to many other pediatric centers, we were using home IV therapy more often to treat the same types of infections and evidence was accumulating that oral therapy was just as good and safer."

When I first arrived at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Medical Center, I quickly noticed how often we used home IV therapies. In some cases this practice was innovative because our team (including physicians, a nurse practitioner and colleagues in pharmacy and home care services) were so experienced with this type of care that we were actually able to send some patients home sooner. For example, we could send a weeks-old infant home to finish treatment sooner than our peer centers.

However, at the same time, it was becoming evident that we might have become victims of our own experience. Compared to many other pediatric centers, we were using home IV therapy when they were using oral therapy to treat the same types of infections. Evidence had accumulated that oral therapy was just as good and safer. Importantly, my colleagues and I began to appreciate more just how challenging it was for parents to administer IV antibiotics for their children–in many cases we were asking them to do 3 or more infusions a day which could take a substantial toll on a family.

Asking questions as a way to combat inertia

We slowly began to change our practice. First, we reviewed our experience using home IV therapy with a critical lens to really see if we were choosing IV therapy for patients who could have been treated just as effectively with oral therapy. We learned that this was a resounding yes–we found that when we looked back, nearly half of the time that we chose IV antibiotics we could have used oral therapy. Even when we chose IV therapy, in many cases we were treating patients for longer than necessary or using a medication that required lots of infusions when a different regimen would have been more convenient for families.

We got to work and really began to change our workflow. We critically appraised our own practice inertia. We collaborated with colleagues across the hospital including other physicians, pharmacists and our discharge planning team, to develop a process via our antibiotic stewardship program where we more intensively scrutinized every decision to use home IV therapy.

We also conducted a study of our patients to learn more about the indirect medical costs (things like missed school and work) that were associated with IV therapy as well as its impact on quality-of-life.

As a result of this work, we were able to reduce our use of home IV therapy by nearly 25% within 18 months. Not only did this ease the burden of home-based therapy for patients and families, these changes led to reduced costs, fewer adverse events with no change in our cure rates.

Change requires every member of the care team as well as listening to patients and caregivers

We learned a lot from this work. First, we learned that sometimes the biggest barrier to making changes is ourselves and our own practice inertia. Second, we found that practice inertia had not just affected us, it had influenced the way our teams anticipated our decisions. Our colleagues had grown to expect that we would routinely recommend IV therapy so in some cases they would arrange to place central catheters before we had even seen a patient to make a treatment plan.

We also learned that every member of the care team is critical to making changes efficiently. And lastly and just as importantly, we were reminded about the importance of listening to our patients and families. Hearing anecdotes about waking up at 2:00 in the morning to administer an antibiotic infusion for the 3rd or 4th time in the day and the toll that it was taking on parents really forced us to question our practice. Although we’ve improved, it is still a work in progress.

Adam Hersh

Utah’s Chief Medical Quality Officer Bob Pendleton describes a strategic challenge faced by many industries, including health care. We are at risk for prioritizing achievement of metrics over our purpose. He challenges us to think beyond metrics to what patients actually need from us: patient-centered, outcome-focused, affordable care.

Patients will ask three things of us over the next decade of health care improvement: help me live my best life, make being a patient easier, and make care affordable. To meet those needs health care must shift—from organizing around a patient’s biology to understanding the patient’s biography.

Improvement work isn’t easy, especially when it attempts to address rising health care costs. Solid organ transplant coordinator Sharon Ugolini and her team led award-winning work implementing new protocols for common tests. That led to more than just reduced patient charges, though — ordering appropriate tests increases value and quality, as well.