year ago, I dove into patient experience by reading the comments. It was a team effort—my nurse coordinator, one of my schedulers, and one of the medical assistants all sitting in a room once a week reading comments. They didn’t always jive with what our scores looked like, so Patient Experience manager Brandon Swensen helped me better understand the data.

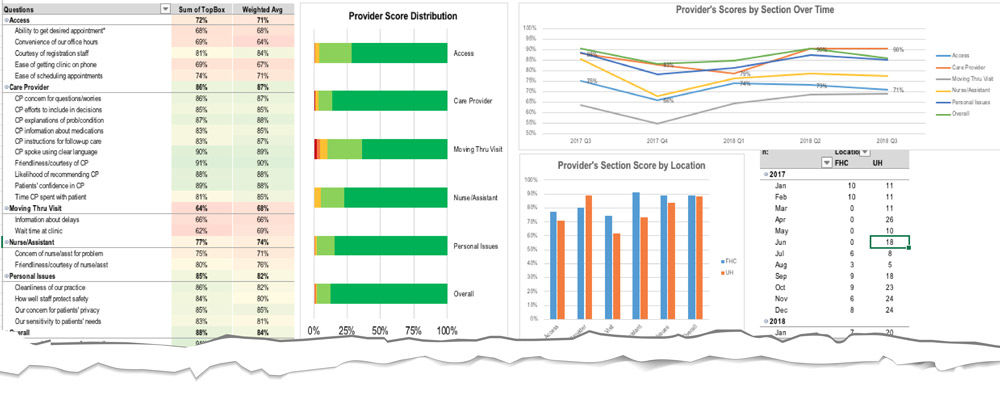

I’m a data person, so I started tweaking the report that Brandon helped me generate, formatting it into a file that I could display to the team. They wanted to see how we were doing, so I created graphs to connect our numeric results with our comments.

#1 Understand the context of comments

Since I’m not rooming patients or making phone calls every day, I include the perspective of people who actually do those jobs. They should help decipher what the comments mean. I came to understand how one patient's negative experience can throw off the roll-up score. Or how, even if a provider has a wonderful interaction with a patient, that might not outweigh the fact that the patient waited an hour. We also look at comments for our providers at other locations to see if there's anything we can learn from the community clinic processes. Understanding that context allows us to see how many different things affect the patient experience.

Then, the data makes it visual, which has a really big impact on employee engagement. The core group that works on the comments and the numbers with me every week, they really like the data. We sit together and slice it by provider and specialty. If one provider in a clinic is doing well but another isn’t, what is that provider doing differently? I can go to our clinic director and talk about how we can help that specific provider, as opposed to just saying, “We are doing terribly.”

Frequency Analysis:

Kirk Hughs gives practical advice on looking beyond the percentile in your patient experience data.

#2 Recognize the differences in your data

Another important component to understanding your data comes from recognizing the difference between percentile and percent. When we look at our actual scores, 80-90% of our patients fall in the very good category. Those patients are very satisfied. We need to use our data to recognize how well we’re doing—not just use it to say, “Our percentile is terrible.” That’s why frequency analysis remains front and center.

We talk about that a lot as a team in our staff meetings. Our 1s are not going to become 5s. People having a really bad experience or a really bad day, that’s not something we have a ton of control over. But changing a 4 to a 5 is completely realistic. Changing a 3 to a 5 is also achievable.

#3 The hard work of standardization is worth it

There’s still so much work to do in terms of standardization. A single source of information containing patient comments, EPE scores, and other metrics is important—and everyone needs to be able to access it. I shouldn’t be the gatekeeper for information that’s not secret. That’s why I created an interactive dashboard on Pulse that my team can access.

The dashboard helps to define our standards. There are normally anywhere between 5 and 10 metrics, and we rate each practice on those while comparing the data side by side. That sets up accountability metrics, which each specialty can report up to the C-suite on a quarterly basis.

If we have a comment, positive or negative, about a specific MA or a specific front desk person, I want to talk about that. Accountability can serve as the means to celebrate the victory of achievement. If a patient references someone who did a really great job, we recognize that person along with the whole group. If those metrics feed into an employee’s merit goals, he or she should be able to easily see where they stand. I really value that kind of transparency.

Leslie Bardsley

What is the strongest predictor of an effective solution? It’s not the size of the committee or the length of the brainstorming session. The best predictor of successful solutions is how well the problem is understood. Investing time in defining, investigating and analyzing the problem can lead to transformative solutions.

Improving value in healthcare means redesigning care to meet patients’ needs. We must push ourselves beyond patient satisfaction surveys to reduce uncertainty, complexity, and confusion in the delivery of care. Matthew Stein, MD, and the Breast Imaging team unflinchingly faced a source of uncertainty for patients: waiting for mammogram results.

The following case study examines a new core competency in delivering value at a system level. At the University of Utah, leaders created integrated oncology teams organized for the patient. Collapsing historical silos and empowering front-line leaders grew adaptive teams that offered better value to cancer patients.