The Challenge

sk anyone in healthcare if they are part of a team, and they will likely say yes. But those are usually discipline-specific teams of nurses, pharmacists, and physicians. Each team delivers care to the patient in a hub-and-spoke model, where each group touches the patient independently. But do we design our care through integrated teams and deliver it through coordinated process? Barriers to integration include our historical hierarchies, a time-starved environment, differences in measurements and goals, and even differences in language. Changing culture requires deliberate planning executed by persistent leadership.

Background

In 2001, the University of Utah Board of Trustees finalized their decision: the university would build a hospital dedicated to the treatment and healing of cancer patients. The pieces seemed in place: Jon Huntsman Sr. had already given $100 million for the completion of the Huntsman Cancer Institute, dedicated to cancer research and treatment, and now he was promising another $125 million.

Some hospital leaders were ready to experiment with a new way to deliver patient care: multidisciplinary teams. But team-based care and a dedicated cancer hospital challenged several institutional norms. To achieve their goal, cancer care would have to be organized for the patient, both in clinical delivery and data organization.

Barrier #1: Physician-centric delivery system

The care-delivery system had long been organized around the physician. Patients experienced physician-centric systems—most clearly evident in the long wait required to see a renowned doctor after diagnosis. It was a traditional department structure—patients would move from department to department on progressive days. One day they might see an oncologist, and then the next week they would return to see a surgeon.

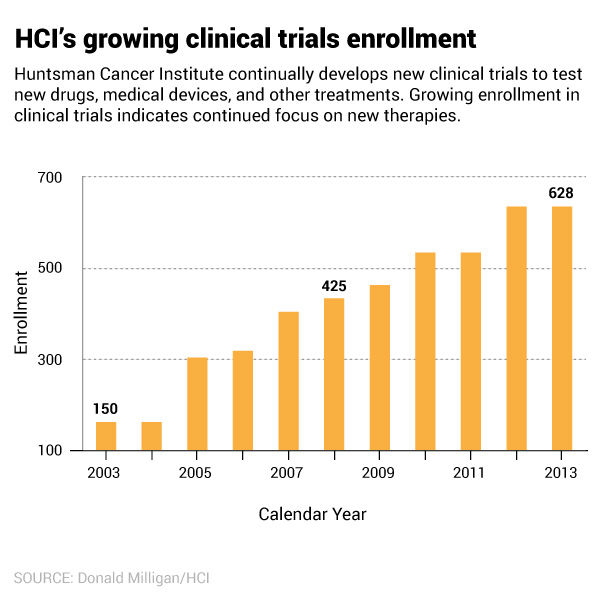

Becoming patient-centered also meant changing the nature of faculty research. Administrators and physicians believed that patients wanted to participate in clinical trials and translational research. But each multidisciplinary team would require more physician-researchers, to be acquired either through internal growth or external recruiting.

Barrier #2: Incomplete data

Another barrier to developing a new cancer program was centralizing medical records. A dearth of data around cancer patients was a problem both at the University of Utah and at a national level, which hindered strategic planning around oncology patients.

The dyad: Physician and administrative leadership

Dr. Sean Mulvihill joined the faculty in 2002 as the chair of surgery. In his surgical practice, Mulvihill specialized in cancers of the liver, pancreas, and bile ducts. He would play a critical role in organizing physicians into effective teams.

Hospital administrator Ben Tanner felt a personal drive to make cancer care easier to navigate and more supportive of patients and their families. Tanner had personally experienced the complicated and stressful nature of cancer care at the University of Utah, and had eventually sought care at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. After treatment, he returned to Utah, determined to bring this model back with him.

The Solution

Step 1: Alignment

In 1999 hospital leaders decided to reorganize cancer care into multidisciplinary teams. Initially, leaders believed that once everyone understood the vision, the doctors would be eager to implement the needed changes. Ben Tanner knew everyone involved had deep personal compassion for patients, so organizing around the patient should be easy.

However, managing how that vision translated into action was difficult. Twelve clinical oncology teams were established: melanoma, breast, thoracic, neuro-brain, urological, gastrointestinal, sarcoma, gynecological, head/neck, hematologic, palliative, neuro-spine. (It has since grown to 13 areas.) Physicians joined the teams with promises of dedicated clinic and office space. Each team consisted of a medical oncologist, surgeon, radiation oncologist, pathologist, radiologist, pharmacist, and social worker.

Yet at first, the teams existed only in name. Organizing a system for the patient proved exceedingly difficult. While the teams of physicians existed, the support structure did not, and patients continued to move through the system in a variety of uncoordinated ways.

Step 2: Team structure

A new physician leader, Sean Mulvihill, helped build the physician engagement that was sorely needed. He created the structure necessary for the multidisciplinary teams to deliver on their promise.

First, Mulvihill looked for new leaders of the multidisciplinary cancer teams. He recruited faculty who had the respect of their peers and believed the multidisciplinary approach. Mulvihill reduced complexity for the teams by setting goals and targets. Each team leader developed goals with Mulvihill and Ben Tanner centered on three areas needed for success: patient volume, research engagement, and financial return.

Mulvihill, Tanner, and the physician team leaders created criteria for autonomy, accountability, and used peer-to-peer transparency to accelerate improvement. Mulvihill also invested time to discuss the big picture so that team leaders could understand the drivers of organizational success. The structure established by Mulvihill empowered leaders for action and experimentation at the local level.

Step 3: Expandnig the team

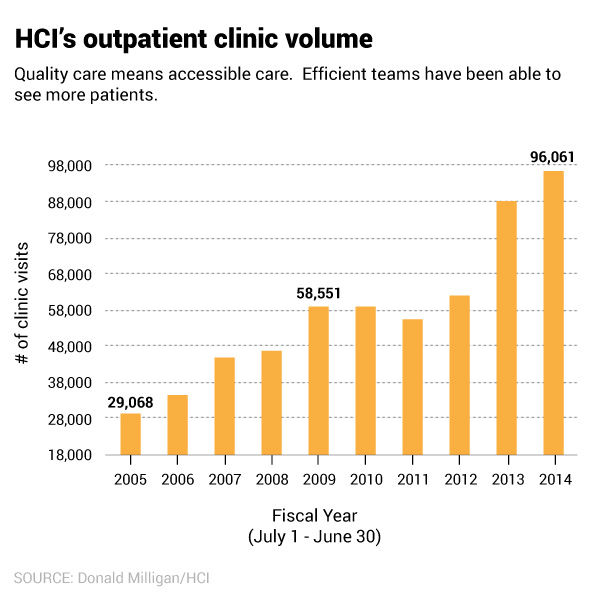

The rest of the team needed to grow to support the physician team. Tanner invested in new positions, such as patient coordinators, to help patients navigate the system and organize appointments.

Small wins fueled support and engagement. The new Huntsman Cancer Hospital shattered expectations by earning money in its first year, instead of losing millions of dollars as everyone expected.

As the team structure gained influence, more people became part of important local decision making. All members of the care team, including nurses and coordinators, were welcome. The message was that more context in the hands of all the people that touched the patient provided better value for the patient.Mulvihill and Tanner's work illustrates principles from Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer's work.: The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2011.

Metrics

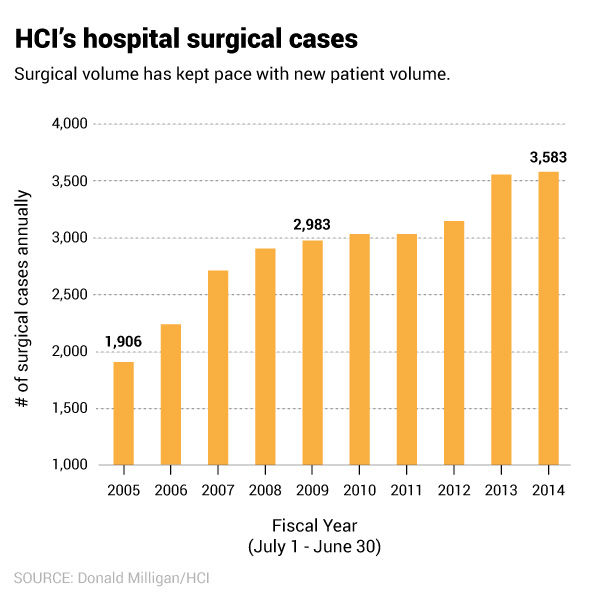

Mulvihil, Tanner and the physician team leaders picked a few metrics to measure success of the teams.

Reflection

Huntsman Cancer Hospital was recently ranked Top 50 by US News. Outpatient and inpatient volume continues to grow, with some of the best patient satisfaction in the county. Researchers at Huntsman have received international attention for their work. Over $35 million is spent each year on direct cancer research.

The key to the Huntsman Cancer Hospital’s success has been three guiding principles: Patients come first, Unified effort—we’re all in this for the same reason: to serve, Excellence in all we do

Teams are constantly auditing their work based on performance metrics (patient satisfaction, clinic volume, and financial returns) and designing team-based solutions. The core of sucess has been the agility of the multidisciplinary teams to respond nimbly to changeMulvihill and Tanner's thinking was also informed by General Stanley McChrystal's book about dynamic teams in the American military. In Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, McChrystal writes about the importance of context. Mulvihill and Tanner fostered a culture that valued context and transparency. They helped each team understand the big picture of organizational success and then supported them as they designed local solutions. McChrystal defines context as a pattern of consistent transparency that empowers a team to continuously and accurately correct actions and decisions. Context increases the effectiveness and agility of teams (Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Portfolio, 2015.).

Mari Ransco

Chrissy Daniels

Steve Johnson

Ben Tanner

Sean Mulvihill

What is the strongest predictor of an effective solution? It’s not the size of the committee or the length of the brainstorming session. The best predictor of successful solutions is how well the problem is understood. Investing time in defining, investigating and analyzing the problem can lead to transformative solutions.

Improving value in healthcare means redesigning care to meet patients’ needs. We must push ourselves beyond patient satisfaction surveys to reduce uncertainty, complexity, and confusion in the delivery of care. Matthew Stein, MD, and the Breast Imaging team unflinchingly faced a source of uncertainty for patients: waiting for mammogram results.

Why do some organizations thrive during a crisis while others flounder? Iona Thraen, director of patient safety, joined forces with her ARUP Laboratory colleagues to learn how the world-renowned national reference lab adapted to the pandemic. Leaders created a culture of safety by putting innovation, learning, and patient-centered care at the heart of all their efforts.