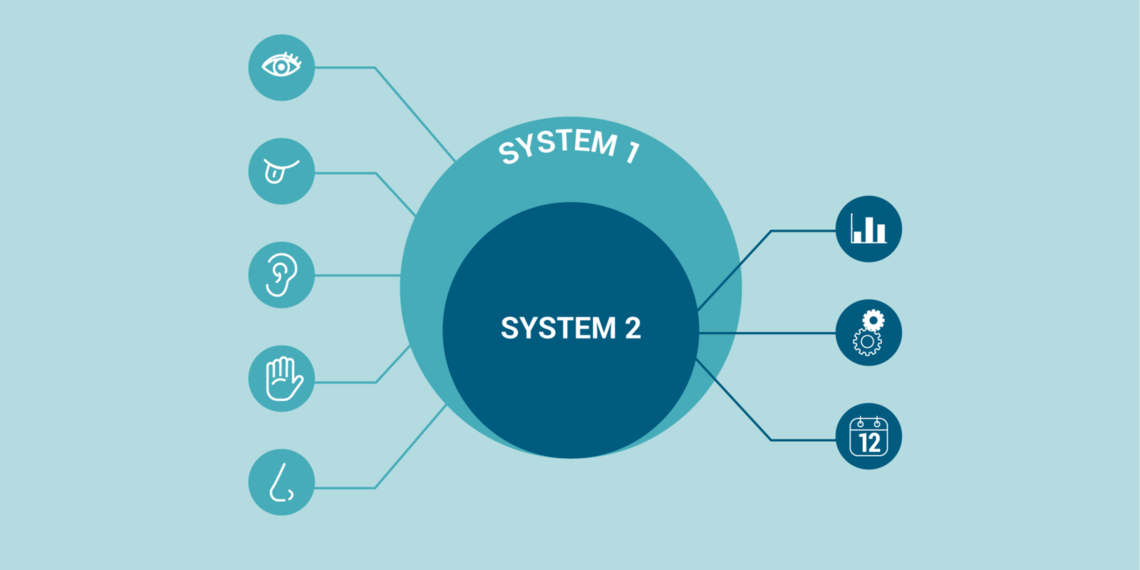

irst introduced by psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his 2011 book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” two types of thinking govern our decision-making. Kahneman labels these different processes System 1 and System 2. We use both to survive every day.

It is important to recognize these systems in our own thinking and that of others. It reveals some of the inherent biases we tend to rely on to make decisions.

System 1: Fast Thinking

Description: Gut reaction, instinctive, emotional first reactions.

Examples: Reacting to hostility; stepping off a curb.

System 1 explains why it’s hard to adopt new evidence into practice

We spend more time in System 1 than we think we do. This concept also has a name in psychology—representativeness. In the 1970s, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky coined the term to illustrate our tendency to quickly jump to conclusions. Their research demonstrates that when making a judgement, we tend to rely too much on the representativeness of a situation (System 1) instead of being patient and gathering more information (System 2).

This type of thinking influences our hesitancy to adopt new evidence into our practice. Consider the last new medical evidence you or your colleagues came across. If System 1 thinking tells us that it doesn’t fit what we think the data “should” show, it often doesn’t matter how deep we go with System 2 thinking—our minds won’t be changed. For all the recent talk of increasing our reliance on evidence-based medicine to make more informed medical decisions, we frequently discount the evidence available to us.

Our preconceived notions and reliance on System 1 suggests why it takes so long for new medical evidence to be broadly accepted. Sometimes there are significant confounders in a study, and it is important to know how to recognize those. Just as often, the data simply goes against our preconceived notions and we justify not accepting the new information. According to established research published in JAMA and IHI, it takes anywhere from 10 to 17 years for new medical evidence to be broadly accepted in the medical community. In general terms, we tend to neglect System 2 in favor of System 1.

System 2: Slow Thinking

Description: Deliberative, logical, systematic analysis.

Examples: Figuring out something; non-urgent clinical presentation.

Why we need to spend more time in System 2, reflecting and analyzing

Studies have shown that increased activation of System 2 thinking can lead to improvements in predictive accuracy. Evaluating and absorbing scientific data, along with routine use of decision-making support, can improve diagnostic prowess and efficacious treatment. Evidence shows that our intuitive impressions are often exaggerated.

Once a month, Utah’s Physician Assistant and Family Medicine divisions participate in the time-honored medical tradition of evaluating a journal article. The goal: practice analytical thinking and empirically assess the evidence. What we’re really doing is deliberately spending time exercising System 2 thinking. It forces us to focus on System 2 instead of purely relying on System 1—a distinction that we all need to make.

Kyle Bradford Jones

Practicing are recorded conversations with a colleague that are shared with the organization. They are conversations between real team members about why the work matters.

Finding evidence to change the status quo isn’t easy; thinking about evidence in terms of how it persuades—whether subjective or objective—can make it easier. Plastic surgery resident Dino Maglić and his colleagues followed their guts and saved money by improving the laceration trays used to treat patients in the emergency department.

Fail fast and often has been Silicon Valley’s motto for years. For medicine, where failure can result in patient harm, failure has negative connotations. Peter Weir, Utah’s executive medical director of population health and a family medicine physician, discusses different types of failures, and how we become better people and better clinicians by talking about our mistakes.