PX Leader Guide

Download the Key Behaviors Leader Guide for a team activity that helps teams learn and apply patient-centric behaviors.

hese two things are often true about health care workers:

- We are experts in the clinical, operational, or technical aspects of our jobs.

- We likely entered health care with deep compassion and desire to help people.

In practice, these characteristics can feel difficult to integrate, or even at odds. There's an explanation for that difficulty—most of us weren’t trained in how to be both clinically expert and compassionate in serious and emotionally charged situations. Even if we have a solid foundation of communication skills, it can be easy to be overwhelmed by the number of tasks and documentation required by our work.

Fortunately, there are a number of simple and meaningful key behaviors that can accelerate our ability to connect compassionately with our patients.

Whether a patient relations specialist or a clinician, focusing our energy on three parts of our interactions—beginning, middle, and end—helps to simplify communication and ensures that patients are treated with respect and understand the next steps in their care.

Set the Stage: Warm Beginnings

First impressions matter everywhere, but patients are particularly attuned to them in health care. In many cases, a patient will have waited a month or more to see a new provider, possibly while worrying about changes to their health. That's a long time to anticipate meeting the team they hope can help. How we craft first interactions sets a positive tone for all that follows.

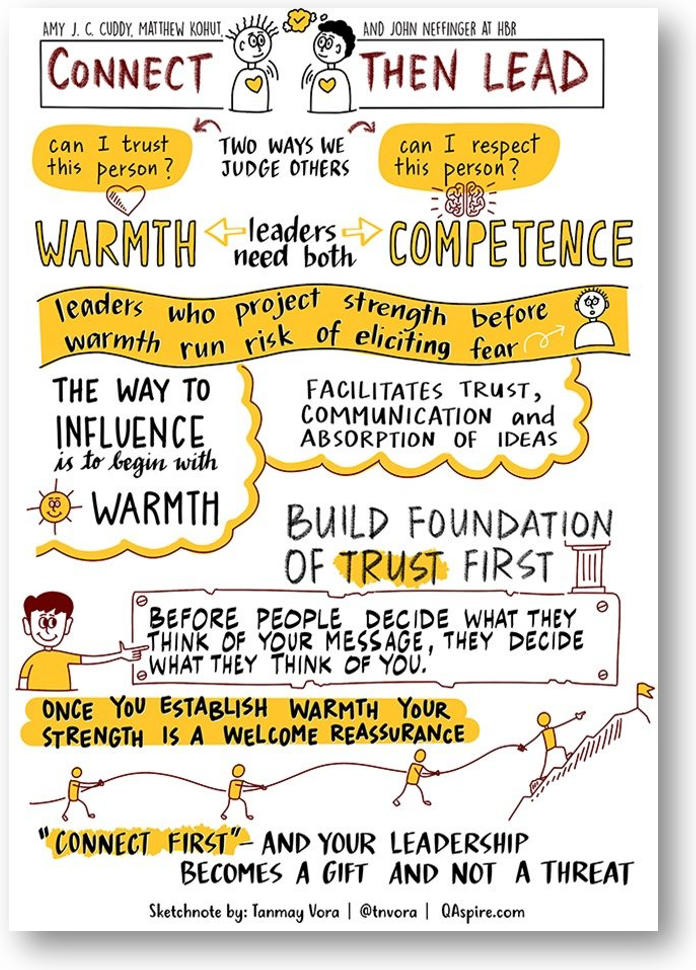

Connect Then Lead

According to Cuddy’s research, “A warm, trustworthy person who is also strong elicits admiration, but only after you've achieved trust does your strength become a gift rather than a threat.”

Amy Cuddy, psychologist at Harvard Business School, identified two traits that account for 80-90 percent of a first impression: trust and competence. Perhaps especially in health care, we often assume that competence is the most important trait. After all, patients go to great lengths to access expert, specialized, and highly trained care. Of course, patients want competent providers, but communication is how a patient perceives competence. According to Cuddy’s research, “A warm, trustworthy person who is also strong elicits admiration, but only after you've achieved trust does your strength become a gift rather than a threat.”

The following behaviors assure patients we want to care for them, just as much as we’re prepared to care for them:

- Review the patient’s chart in advance

- Knock and ask to enter a patient area

- Smile and make eye contact

- Greet patient and support people

- Address by chosen name and pronouns

- Speak in patient’s preferred language via a qualified interpreter

- Introduce yourself

- Introduce colleagues when appropriate

- Inquire about the patient (e.g., “How are you feeling today?”)

- Allow the patient to answer without interrupting

Substantive Middles: Align on What Matters Most

After we’ve established trust, we can get into the content of the interaction. This may look like completing an intake, registering a patient, discussing a patient’s concerns, explaining a new diagnosis, performing a procedure, taking vital signs, discharge teaching, or setting up a tray of food.

In every case, skillful listening is perhaps the best tool we can employ to maximize meaning in our interactions. When we actively listen to every patient, we demonstrate respect for their journey. Listening gives us a valuable window into what matters to the individual in this moment, which means we can tailor our expertise more precisely. Through this collection of shared knowledge, providers and patients can be true partners in creating an authentic, viable care plan.

Dr. Rita Charon, a pioneer of narrative medicine, said:

"I used to ask new patients a million questions about their health, their symptoms, their diet and exercise, their previous illnesses or surgeries. I don’t do that anymore. I find it more useful to offer my presence to patients and invite them to tell me what they think I should know about their situation.…I sit there in front of the patient, sitting on my hands so as not to write during the patient’s account, the better to grant attention to the story, probably with my mouth open in amazement at the unerring privilege of hearing another put into words—seamlessly, freely, in whatever form is chosen—what I need to know about him or her."

You may read the above quote and think, “I don’t have time to listen the way my patients want, or the way I’d like.” You’re not alone. A Harvard Medical School study found that 56% of health care clinicians feel they don’t have enough time to treat patients with compassion. However, several studies found that listening and responding with compassion takes 30-40 seconds, and on average, patients have two concerns per encounter. It may not take as long as you think to be present and respond to patients.

Additional behaviors like the ones below can help patients and their caregivers align on what matters most during the encounter:

| How to Align | Tips for Application |

|---|---|

| Sit down and face the patient. | Adjust this as needed according to the encounter type—the important thing is that your nonverbal communication conveys your presence. |

| Explain what you’re doing, and keep the patient informed throughout the process. | “I'm waiting for your insurance to verify with our system—give me one more moment and we’ll have you checked in.” |

| Align on an agenda. | “What would be most meaningful to you to address today?” |

|

Anticipate and batch complimentary tasks. |

For example, for an acute care hospitalized patient—weigh the patient as you help them transfer to the chair and change the linens while they are up. This requires some planning, but it’s mutually beneficial. |

| Adjust your delivery according to verbal and nonverbal cues. | Use the patient’s responses to guide the direction of the conversation. For example: “That was the technical explanation – I know it can sound complex. Let’s talk about what that means for your day-to-day life.” |

| Check for understanding. | This can be done in a variety of ways—fine tune your approach to feel respectful and not patronizing. For example: “Your husband will be changing your dressing at home, right? Would he be willing to do this change with me in case that sparks any questions I can answer while you’re still here in the hospital?” |

Graceful Ends: Close the Encounter

Taking the time to build trust and listen can make endings more natural, allowing patients to feel heard and providers to stay on time. If we have taken the time needed to connect in the earlier stages, the research reveals something counterintuitive: giving time actually gives you time.

The following behaviors can help close an encounter in a gentle way that feels comfortable to both parties:

- Ask in an open-ended wayAn open-ended question (not one phrased in a way to elicit a “no”) is important in understanding final concerns. Patients sometimes wait to bring up important topics until the end of a visit.—“What questions do you have?” or “What concerns do you have?”

- Explain the next steps.

- Thank the patient sincerely.

- Walk patient out (if applicable).

Apply It: The Benefits Are Clear

Working Together Toolkit

View the Patient Experience Toolkit for a host of resources that build teamwork centered on the needs of patients, caregivers, and families.

The research is clear that demonstrating compassion through simple behaviors like the ones above makes an extraordinary difference for patients. And the benefit does not stop with patients—these behaviors can also be an antidote for burnout among healthcare professionals.

If these actions feel daunting to apply at once, consider adopting one at a time. Test it—did it make a difference? How did you feel afterward? How much time did it actually take? How did the patient respond? If it didn’t feel natural, how can you adapt next time?

With time, we can all develop personal practices that feel deeply compassionate to our patients and authentic to us as individuals.

Kathryn Young

The patient experience team shares resources to build coordination and teamwork centered on the needs of patients, caregivers, and families.

Our words can build, or erode, trust with others. Manager of Patient Experience Operations Ember Hunsaker offers insight into how our words may be helping, or harming, those around us and how to balance the scales.

What do patients want? University of Utah Health’s patient experience team reveals what fifteen years of evolving qualitative analysis of hundreds of thousands of patient voices have taught us.