IMPACT CASE STUDY

Businesses all over the world have experienced unparalleled disruption due to the pandemic. So why did ARUP Laboratories thrive while so many struggled?

This Impact Case Study explores a key cultural driver—psychological safety—that propelled ARUP through COVID complexity. We unpack the three basic tenets of a psychologically safe workplace that you can use right now.

dam Barker was watching television at home with his wife, a physician at U of U Health, in early March last year when the story broke: the northwestern Lombardy region of Italy was shutting down. By this time, the coronavirus had been rapidly infecting people throughout the world. It was hitting Lombardy particularly hard.

“That’s where we get all of our media and our swabs,” Barker said, turning to his wife. “If we lose that, the whole world loses its supply.”

As the R&D director at ARUP Laboratory, Barker’s concerns were hardly theoretical. COPAN Diagnostics, located in the Lombardy region of Italy, is one of the primary manufacturing facilities for nasopharyngeal swabs. These pieces of laboratory testing equipment may look like common drugstore Q-tips, but they are very specialized. They were sorely needed to test for a new and rapidly spreading virus. Instead, the entire world lost access to this critical test supply.

The next morning Barker joined with colleagues at ARUP to assess their new situation. He learned that ARUP had about 10 days of swabs left. That wasn’t the only challenge. COPAN also produced all the media ARUP needed for molecular assays, serology tests, and other tests. The lab was in danger of grinding to a halt at a most crucial and emergent time.

Learning what made ARUP thrive

I (Iona) work as the patient safety director for U of U Health Hospitals and Clinics, so I was captivated when I heard Barker recount his experiences at a virtual clinical update several months after the pandemic began. The complexity ARUP faced was not unique; thousands of labs all over the world were experiencing similar shortages and challenges. So were financial institutions, small businesses, hospitals and governments. Why did ARUP thrive while so many organizations struggled? What could we learn from them to improve our own practices?

In my interviews with colleagues from across ARUP’s operations, including leaders and employees from up and down the ranks, I learned that ARUP’s culture was at the heart of its success. Leaders facilitated rapid innovation and urgent response protocols that kept everyone working toward the same goal. Frontline workers were encouraged to put forward their own ideas. Even as their supply chains were falling apart around them, ARUP’s collaboration and focus helped them respond with aplomb to the COVID-19 crisis.

A crucial concept for complex systems

In workplaces all over the world people often decide to remain silent when it would benefit them to speak up. Amy Edmondson, a professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School, attributes a natural human trait that contributes to this silence: nobody wants to look “ignorant, incompetent, intrusive, or negative.” The best ways to do that are to not ask questions, to hide weaknesses and mistakes, and to avoid speaking up when views are contrary to those of peers or superiors.

In some organizations, people keep quiet because they worry about looking bad. They spend their time managing others’ perceptions. In other organizations, employees freely share their thoughts and ideas. They spend their time engaging in meaningful interactions where people can learn and get better. What’s the difference between the two? Psychological safety. According to Edmondson, psychological safety refers to the expectation that anyone can speak up with questions, concerns, and ideas. It is a concept that is crucial for complex systems like ARUP.

There are three basic tenets in a psychologically safe workplace:

-

Frame the work as a “learning problem” and not an execution problem. Readily acknowledging situational complexity and team interdependence opens the door to solicit everyone’s insights.

-

Acknowledge your own fallibility. Nobody has all the answers, and leaders should acknowledge as much to peers, subordinates, and colleagues so others feel comfortable speaking out or raising concerns.

- Be a role model for curiosity. When everyone in an organization is asking questions, it opens the door for others to ask questions.

Articulating the problem

“A learning problem, not an execution problem.”

The challenges of COVID-19 were compounded for ARUP by the fact that their services as a world-renowned, national reference laboratory were in higher demand than ever. With their supply chain completely disrupted, they had to find a way to continue testing entirely in house in spite of the loss of two key supplies—swabs and media—since they were not available from their main supplier. Key leaders met in an “executive war room” around the clock for several weeks trying to tackle the supply chain problem.

Arthur Moes, a supervisor in the purchasing group, got the first call from Barker on a Saturday. His team was already looking at potential supply chain issues out of China, but this was an entirely new challenge. Testing swabs and media from a single provider in northern Italy were necessarily critical to identifying cases that were now in the United States. The team convened around a central purpose of rapidly reconfiguring the supply chain to get new materials. Nobody knew exactly how they would accomplish it, but they all understood the goal.

“Acknowledge your own fallibility.”

Michael Bevan, supply chain director at ARUP, was relatively new to the organization. He had two decades of experience in global supply chain operations, but was new to health care. Trying to sort out a supply chain issue in an unfamiliar industry in a global pandemic was like “drinking from a firehose,” he said, but Bevan’s expertise—working in and overseeing factories and supply chains globally—was essential to the success of the team. Bevan helped his fellow leaders understand the strategies, actions, and needs to help direct ARUP teams and the organization. Rather than discount his contributions because of his lack of experience in health care, the ARUP leadership team welcomed his input. He also had to recognize the areas where he needed help from his team and from others in the organization.

From the beginning of the crisis, teams were encouraged to brainstorm solutions and the organization would figure out how to execute on the best ideas. It was part of an organizational shift that Bevan and his team started before the pandemic.

Learn about Value Teams

Michael Bevan shares a step-by-step overview of the why, how and what of Value Teams here.

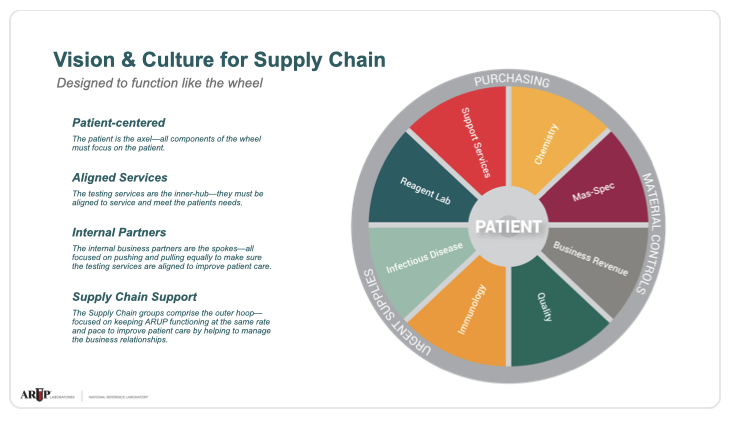

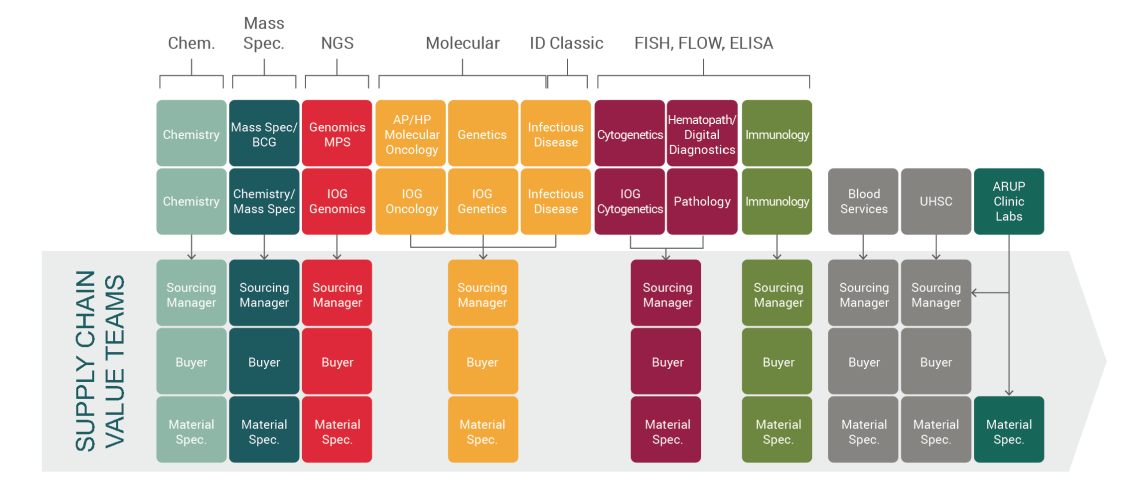

ARUP structured its supply chain around the idea of “value teams” that were focused on a common goal or objective and integrated across non-traditional boundaries, rather than traditional top-down hierarchical decisions. Bevan implemented this structure based on his observations of challenges related to communication, collaboration, and decision-making. Each team within ARUP—R&D, technical operations, supply chain, and medical directors—had its own value group. The organization as a whole also had a value group with stakeholders focused on three things: what do we need, what opportunities are out there, and what’s changing in the industry.

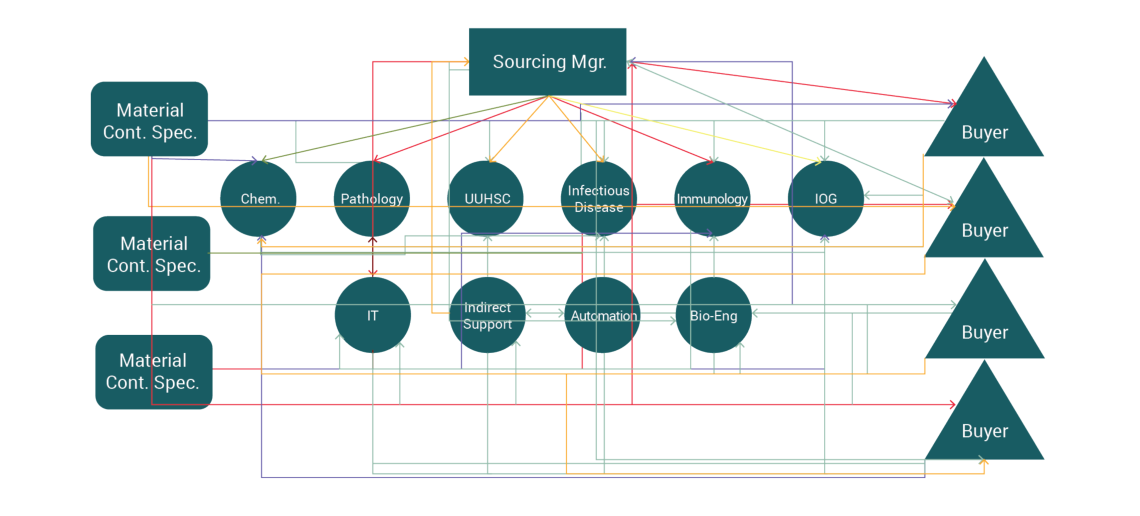

"Chaos" - ARUP's Former Supply Chain-Focused Structure

Value Team "swim lanes" helped ARUP rapidly organize during COVID-19

This strategic shift allowed each person to operate in their own “swim lane,” and trust that other members of the team were doing their part in a parallel lane. Rather than chaotic and disparate operational silos (warehouse, purchasing, etc.), everyone worked together to get the supplies necessary for the work to continue. These structural changes helped ARUP to be nimble in a rapidly changing environment.

As a new patient safety director, I wanted to know what people with longevity, from the ranks, thought about how ARUP was structured. I got that from Eric Peterson, a sourcing manager for ARUP. Peterson started out over a decade ago in the warehouse. About five years ago he moved into his current role, where his focus has primarily been on infectious diseases. It was in the middle of those five years that Bevan instituted his structural changes. Peterson confirmed for me what I anticipated: the crux of ARUP’s ability to execute so quickly was reliant on how they were organized.

That pre-pandemic strategic realignment served as a foundation that facilitated success once COVID hit. With an effective process in place, they could focus on the problem at hand. There was significant trust among divisions and a willingness to admit when help was needed. They had an organizational culture of learning and sharing. Crucially, they had permission to fail, which Edmondson argues is essential in a psychologically safe workplace.

Understanding the Solution

ARUP went from a company with a global supply chain to one that had to create its own transport media in house, essentially overnight. Simultaneously, demand increased from thousands to hundreds of thousands of tests in the span of a couple weeks.

Barker went to his leadership team and clearly laid out what they needed. They were getting about 5,000 test collection kits per day when COPAN cut off shipments. He diluted the existing supply so it would last twice as long (about a month), buying themselves some time that would allow them to plan. Then he asked the question, “What if we never get any media again [from outside suppliers]?”

The team at the reagent lab spent that month coming up with a plan to make their own kits, and by April could produce 6,000 a day in-house with 73 team members assembling them by hand. The production capacity increased to 9,000 kits a day in July and they prepared to open an automated production facility to create 40,000 per day by September.

"Be a role model for curiosity."

The ability to ramp up production often boiled down to the example set by leaders:

-

Asking questions (“modeling curiosity”) to get to a better and more efficient process

-

Leading with humility by jumping in wherever and whenever needed

When Lincoln Hirayama, group manufacturing manager for ARUP, learned they would need to produce their own media kits, he asked for volunteers from around the organization. He and several dozen others stood side-by-side (at a safe six-foot distance) to assemble the kits by hand. High-level supervisors and brand new employees spent 18 hours a day for weeks at a time on the assembly line. That willingness to pitch in permeates the entire team and is one of the key ingredients of a psychologically safe environment: humility.

When Lincoln Hirayama, group manufacturing manager for ARUP, learned they would need to produce their own media kits, he asked for volunteers from around the organization. He and several dozen others stood side-by-side (at a safe six-foot distance) to assemble the kits by hand. High-level supervisors and brand new employees spent 18 hours a day for weeks at a time on the assembly line. That willingness to pitch in permeates the entire team and is one of the key ingredients of a psychologically safe environment: humility.

Creating a psychologically safe environment requires everyone from the top down to model humility, learning, and curiosity. It also requires letting up on the brakes sometimes, in the words of Edmondson, so people feel free to engage and offer their insight.

Meanwhile, over in the R&D department, Mark Astill was trying to figure out where to get media. Ultimately, they decided to make it in-house, rather than find a new supplier, by reverse engineering a recipe from publicly available information. The result is the now-branded ARUP Transport Media (ATM). After the new media was validated for all relevant testing at ARUP, the recipe was published for the rest of the world to use. It has since proven to be an essential product and has now replaced the original, outsourced product. It also costs less.

Measuring the Impact

The COVID-19 situation is still ongoing, so we are still learning the full impact from ARUP’s rapid change and innovation. What we do know is impressive.

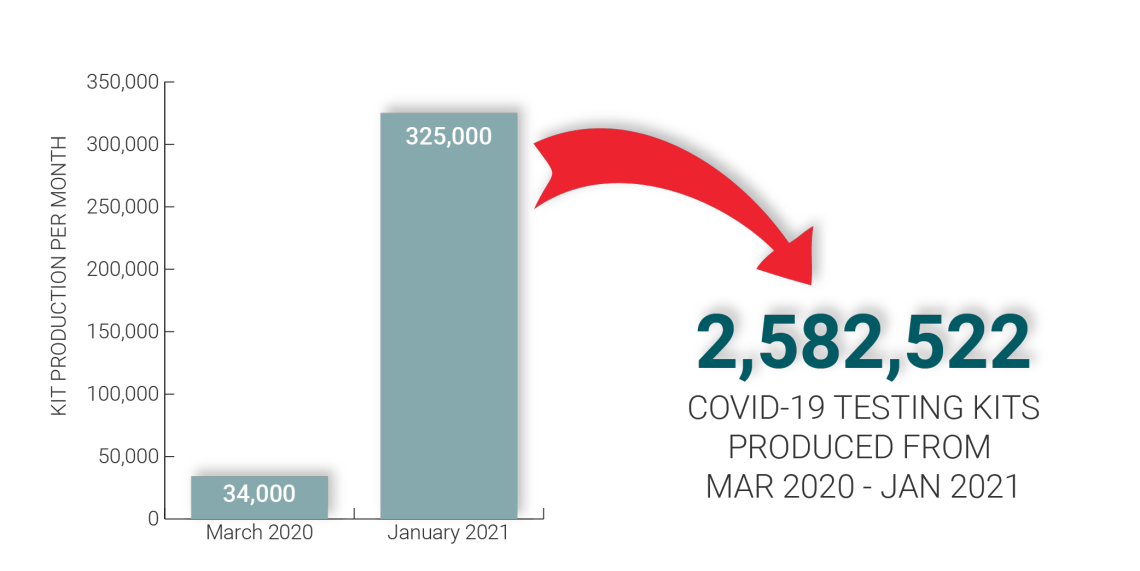

COVID-19 Collection Kit Production

Collection kit production increased from 34,000 kits/month in March 2020 to 325,000 kits/month—that's a total of 2.5 million kits between March 2020 - January 2021. This increase was possible due to innovation and automation of the collection kit production process.

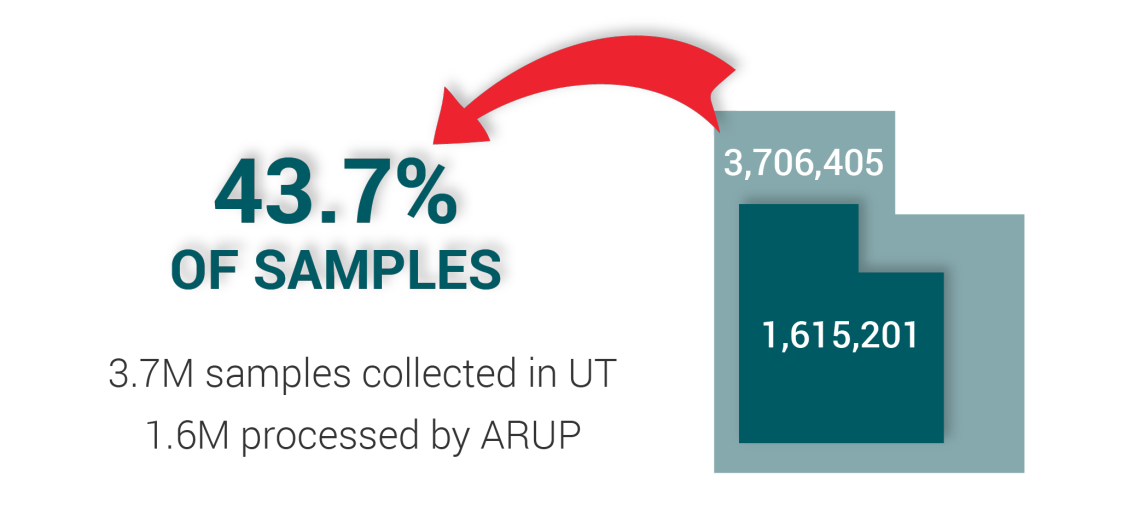

COVID-19 Samples Processed

ARUP has performed more than 1.6 million COVID-19 samples to date—that's more than 40% of samples processed in the state of Utah. This would not have been possible without the collection kit availability.

The reflection

It may be early, but as a patient safety professional I’m already looking for the lessons we can learn from ARUP. One of the lessons that is already clear is how much an organizational culture can impact innovation and adaptation in times of rapid transition.

For ARUP, it started before the pandemic when they revamped their culture to better support organizational values of innovation, learning, and patient-centered care. That move strengthened interpersonal relationships and trust so everyone could provide input when it mattered most. Bringing together ideas from every division and value group helped ARUP move quickly through the constantly changing situation that has been the worst global health crisis of our time.

COVID has functioned as a catalyst. In some organizations it has ignited a vision and accelerated high-function performance; in others, it has been a destabilizing and crippling force that has accentuated the dysfunctional breakdown of an entity. It depends on the underlying foundation of an organization as to whether it will rise or fall.

The time has not yet arrived when ARUP leaders can reflect on what transpired and how they shifted so quickly to meet the demands of COVID-19. We are still in the thick of it. But that day will come. And when it does, examining their process to discover what worked (and what didn’t) will help us carry valuable lessons forward. This case study is the beginning of that process.

Acknowledgements

Case studies involve months of interviews, analysis and iterative drafts to develop. Special thanks to the following key contributors: Accelerate U of U Health: Tracy Hernandez, Writer; Isaac Holyoak, Deputy Editor; Marcie Hopkins, Graphic Designer; Kim Mahoney, Instructional Designer; Iona Thraen, Associate Editor and Director of Patient Safety. ARUP: Michael Bevan, Director of Supply Chain; Lincoln Hirayama, Group Manufacturing Manager; Arthur Moes, Purchasing Supervisor; Peta Owens-Liston, Editor; Eric Peterson, Sourcing Manager Lead; Mark Astill, Vice President, Research and Development.

Iona Thraen

Kim Mahoney

Isaac Holyoak

Tracy Hernandez

Michael Bevan

Lincoln Hirayama

Arthur Moes

Eric Peterson

Peta Owens-Liston

Mark Astill

Your gut tells you a process could be better than it is—how do you back that feeling up with hard data? Senior value engineer Luca Boi shows how undertaking a baseline analysis can jumpstart your improvement project.

Finding evidence to change the status quo isn’t easy; thinking about evidence in terms of how it persuades—whether subjective or objective—can make it easier. Plastic surgery resident Dino Maglić and his colleagues followed their guts and saved money by improving the laceration trays used to treat patients in the emergency department.

What is the strongest predictor of an effective solution? It’s not the size of the committee or the length of the brainstorming session. The best predictor of successful solutions is how well the problem is understood. Investing time in defining, investigating and analyzing the problem can lead to transformative solutions.