The Challenge

The Value Equation of Timely Admission

Once it’s determined a patient should be admitted to the hospital, getting the patient to a unit safely and efficiently to their bed is good for patients and the system. The challenge is to eliminate the waste of waiting—the patient, the empty bed.

Utah’s value equation is defined by the patient and is Value = Quality + Service/Cost. This case study demonstrates that faster transfers improves safety through getting patients quicker access to appropriate treatment; service in removing unnecessary suffering patients experience waiting for treatment to begin; and charge decreases that patients incur while being boarded in the Emergency Department.

evin Curtis inherited a problem that had been hanging around for years—psychiatric patients boarding in the emergency department (ED), waiting for a bed. What’s a new manager to do?

The conventional wisdom given to new managers is to wait, learn about the unit, get to know the people and only then work to improve. Curtis took another route. He used Utah’s value improvement methodology to work on the problem as a team. The value improvement methodology keeps the focus on the process. It provides a structure to examine the “it’s always been done this way” problem (in this case, delay to admission), and identify and prioritize the causes. It gives employees a meaningful role in analyzing problems and designing solutions. The result is more engaged and empowered teams.

Background

Kevin Curtis joined University of Utah Health in 2010 as a social worker in the main hospital’s inpatient psychiatric unit, 5 West. Although Curtis never planned to work in a hospital, he discovered he enjoyed the hospital environment and helping patients in crisis. After a few years, Mary Talboys asked him to help open the Wellness Recovery Center at the main psychiatric hospital, University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI).

Curtis became familiar with systemic problems patients faced during his time at the Wellness Recovery CenterThe center provides patients with a mental health diagnosis with intensive support without pulling them away from everyday life. The Wellness Recovery Center also provides a softer landing as patients are discharged.. He reflected on the limbo of waiting in the ED. “At the WRC, I really learned about what is the right place for someone to be. I thought about what it meant to need inpatient care, and what it felt like to be that person in the ED, waiting and being in such crisis, needing the help and not knowing what is next.”

Understanding the pain of waiting prepared Curtis for his next job: managing UNI’s admissions clinical team at the Clinical Assessment Center (CAC). Social workers collaborate with billing specialists to assess and coordinate a patient’s admission to one of UNI’s 150 beds. Patients can self-refer (also known as “walking in”) or be referred from an emergency department. The two most common referring sources are the emergency departments of University Hospital and Primary Children’s Medical Center (PCMC). Self-referrals are UNI’s fourth largest source of new patients. The CAC was a larger stage for Curtis’ passion of helping people in crisis.

Curtis’ predecessor recommended that he sign up immediately for U of U Health’s lean six sigma green belt course. Curtis agreed, saying, “I knew I wasn’t going to do an MBA, and they don’t teach administrative skills in MSW school. I was excited to find out there was a structured way to learn improvement that was challenging and enlightening.”

One month after Curtis started, an old problem of wait time became Kevin’s top priority. Psychiatric patients bound for UNI were waiting in the ED, sometimes up to 8 hours. UNI’s physician leaders, administrative leadership, and CAC’s staff had long been working on solutions to get patients over to UNI faster. The many factors delaying patients’ acceptance and transfer to UNI felt overwhelming: the speed of acceptance, doctor to doctor communication, nurse to nurse communication, etc. It was overwhelming. Curtis enlisted his value improvement coach, senior value engineer Dane Falkner, to help apply the value improvement methodology to this chronic delay problem.

1. Project Definition

Curtis thought about why this project mattered and who would help him reduce delays. This phase includes identification of the team, project vision, defining SMART goals and scoping.

Why should you use a methodology?

Following a proven, structured, and balanced quality improvement methodology guides the right questions to solve the right problems. Organizations that know how to improve performance faster adopt a standard methodology. U of U Health’s improvement methodology combines lean, six sigma, and PDSA approaches.

Team: The people who do the work

Because the value improvement methodology emphasizes the importance of involving those who do the actual work in the investigation and design, Curtis included a small group of coworkers. He included Steph Johnson, the manager of the business side of the admissions process (the Psychiatric Admission and Billing Specialists, or “PABS” team), social worker Natalie Schuman and PABS team supervisor Gentry Walton. Curtis remembered “I was such a novice, and I knew it was so important to get the people involved who knew our day to day processes. I knew that they would also be the ones who have to help enact any new process.”

Vision: "We are the treatment"

The team crystallized their vision about why this was important work and how it would benefit patients and the team. Curtis thought it was crucial to connect any changes with the team’s intrinsic motivation of helping people in crisis. Curtis reflected, “These people work here for a reason, they are social workers for a reason. No one wants to be a gatekeeper to anything. The sooner those patients can get to us, the better. We are the treatment.”

SMART Goals

Curtis wrote two companion SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound) goals.

- Increase the number of UH ED transfers within an hour from 81% to 95% by 12/31/16.

- Increase the number of PCMC transfers within an hour from 50% to 95% by 12/31/16.

Scope

Curtis remembered that, “Initial attempts to impact this problem were too broad, they tried to fix the whole CAC at once.” To combat this, Curtis limited the scope to those steps which were completely within the control of the CAC: From the point of transfer request to reserving an open bed on a unit. This step confirms that, yes, the patient can be admitted. As Kevin put it, “We limited the process scope to getting to the yes.”

2. Baseline Analysis

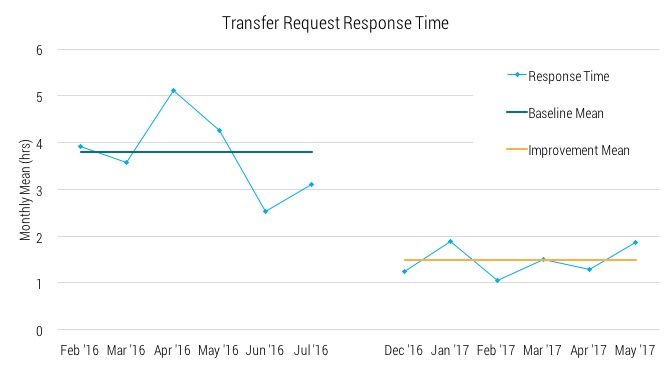

Why was it taking so long to approve a patient transfer to UNI? Curtis’ analysis included a year’s worth of patient transfer data and a process map. The data revealed the scoped process had a mean turnaround time of 3.8 hours and 17% took 8 hours or longer (all sources except self-referrals).

At their first meeting, the team created a revised transfer intake process map focusing on the processes and procedures that are within the control of CAC workers. Curtis recalled that the map “started out a little too tidy,” so value engineer Dane Falkner turned the process map into a cause and effect diagram, asking the team to identify delays according to where they originate in the process. The early back and forth communication culminating in a fax from the transferring facility was identified as a major source of delay.

3. Investigation: Use data to direct the project

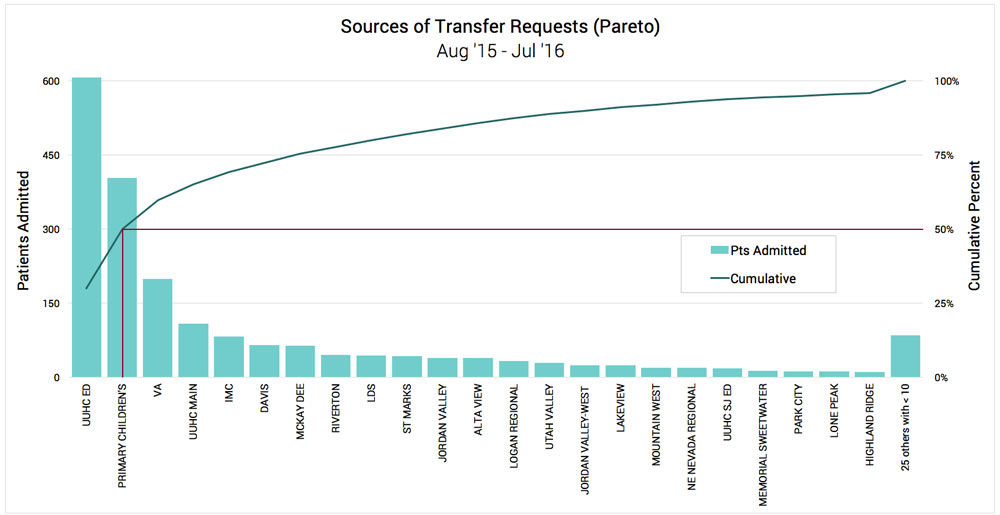

Curtis and Steph Johnson narrowed the scope further in two important dimensions. First, they limited the focus to transfers from UH ED, PCMC ED. Here’s a Pareto analysis of all transferring sources showing these two facilities contributing a combined 49% of all transfers.

Pareto analysis reveals U of U Health and PCMC contribute to half of all UNI transfers

Curtis and the team also completed a fishbone diagram to understand the causes of the delay. The team identified some fine-point process issues (e.g., handoffs of in-process work being delayed) but the most significant discovery was that transfer requests took a back seat to nearly everything else in the CAC (e.g., self-referrals, clinical intake assessment, calls from the UNI providers).

4. Improvement Design

MEET THE TEAM

Kevin Curtis

Steph Johnson

Natalie Schuman

Gentry Walton

Curtis and the team met to design a new process. Natalie observed that the existing process, which concluded with a fax from the referring facility, contained lots of information pertinent to later processes. The CAC only needed four basic bits to reserve a bed. “Rather than wait for the fax,” Natalie suggested, “why don’t we just ask for these four things when the call comes in?” It was a breakthrough idea: break up the big batch of information into smaller batches based on when the information is needed.

The investigation revealed that there was enough transfer volume to justify a dedicated social worker who would focus on coordination and clinical review. This new role, the transfer specialist, would complete a checklist based on the new protocol during transfer request calls. It didn’t require hiring, just a reshuffling of current staff. On the PABS side of the operation, they designated an on-call transfer role. The point person can respond to transfers within five minutes.

5. Implementation

Curtis and the team brought the new protocol to the larger CAC to pilot for three weeks. Importantly, Curtis wanted feedback. He asked the entire team to give any feedback to the small group who had designed the process. Feedback could come anytime, as informal as the employees wanted.

Schuman and Walton did the hard work of convincing their peers to give the new process a try. The common complaint was that they were already working as hard as they could. Curtis knew that while it was easy to get on board with the vision of faster and more efficient transfers, it was hard to see how it could happen. It was important that people had a chance to try it out, see if it worked, and give feedback.

The pilot results

After three weeks, the team saw their mean drop from 3.8 hours to 1.6 hours (58% decrease) and 54 of 65 (83%) were complete in under an hour compared to the baseline rate of 63%. The staff was surprised at the impact especially since, as hoped there was no additional work and no one had to work harder. Since the acceptance occurred more quickly, all of the downstream tasks went faster too, and the patient could get to UNI even sooner. During the meeting to discuss the pilot data, the conversation quickly shifted from ‘does it work?’ to ‘we know it works, let’s try to make it easier.’ Curtis asked the team for their input in modifying the process so it was even easier to maintain.

The team suggested a few important changes: a dedicated phone line for transfers and rotating duty as the social worker transfer specialist. The new transfer specialist role, which is primarily clinical review and coordination, can be tedious and deprives social workers of the more rewarding part of their job: patient interaction. Today, it’s an assignment that rotates among the CAC’s social workers.

6. Monitoring

Six months of results are shown here. They have maintained the improvement experienced in the pilot. Not only have the two important measures of mean and percent less than one hour decreased, their overall performance has become much more consistent: baseline standard deviation was 7.1 hours and after six months it was 3.7 hours.

Data charts

This histogram shows the portion performed in under an hour jumping to 82% in the first six months of the new process. It also shows the accompanying decrease in three of the other four bins. For instance, patients waiting over 16 hours has decreased from 9.3% to 1.9%.

This histogram shows the portion performed in under an hour jumping to 82% in the first six months of the new process. It also shows the accompanying decrease in three of the other four bins. For instance, patients waiting over 16 hours has decreased from 9.3% to 1.9%.

Reflection

Speeding up transfers to UNI has been a balance, reflects Johnson. “We are always working at efficiency—getting the patient here, while making sure that the bed is ready.” This project makes admissions more predictable and regular. Curtis comments “The hospital as a whole has benefited because we can spread admissions out and not rush things.”

The new workflow allows individual social workers to accept patients immediately to UNI without extra work. Social worker Natalie Schuman comments that her colleagues are more individually empowered to make decisions, and that increases overall staff engagement.

Lastly, Curtis has found that the increased dialogue with referring facilities has improved the relationship. “Because of this project, we realized that UNI is the best possible place for children needing inpatient psychiatric care and that spending time in a medical unit was not beneficial for the child or the family,” said Dr. Chris Maloney, chief medical officer at Primary Children’s Medical Center. Curtis has also observed increased trust. “We would tell the ED that we were working fast, but they didn’t necessarily believe us. Now, we share data of our time to accept, and we worked on solutions together. When there is a problem, we tell them we are trying and they believe us.”

Steve Johnson

Mari Ransco

Chrissy Daniels

Dane Falkner

Kevin Curtis

Director Lora Stratton details how Utah’s Cardiovascular Center leveraged team creativity and rapid problem solving to make—and sustain—the shift to virtual care. Cardiologist Anu Abraham shares what it looks like in practice.

Improvement isn’t just for one area of academic medicine. The right improvement can mean improved patient and trainee experience, reduced cost and a more engaged staff. Nurse Manager Bernice Tenort, physician Brett Einerson, and an interdisciplinary team ended up solving many challenges by tackling a long-standing problem: wait time in labor and delivery.

If in previous dojo posts, you still haven’t found what you’re looking for, today’s post will satisfy your desire. In it we describe the mysterious ways of Drs. Chris Hull’s and Mark Eliason’s clinic practice. Unless you’re a patient, you can’t witness their clinic, but this post is even better than the real thing.