ealth care has been coined “uniquely inefficient” when compared to other industries, with the blame largely placed on the prevalence of insurance and government regulation. You often hear, ‘if people just knew the price, then health care costs would go down.’ In their January 10, 2017 HBR article,“ What the Cost of a Trip to the Vet Tells Us About Why Human Health Care Is So Expensive,” professors of economics Amy Finkelstein and Liran Einav compare the similarities of two industries where decision-making is often emotionally and financially charged. Their findings run counter to price transparency. Finkelstein and Einav found that even when pet owners know the price, they still favor increased spending.

Health Care vs. Pet Care

The authors unpack an impressive amout of data to support their assertions in their NBER working paper, “Is American Pet Health Care (Also) Uniquiely Innefficient?” Marcie Hopkins, patient experience project manager (and graphic design phenom for Accelerate), highlighted four key findings in the following visuals.

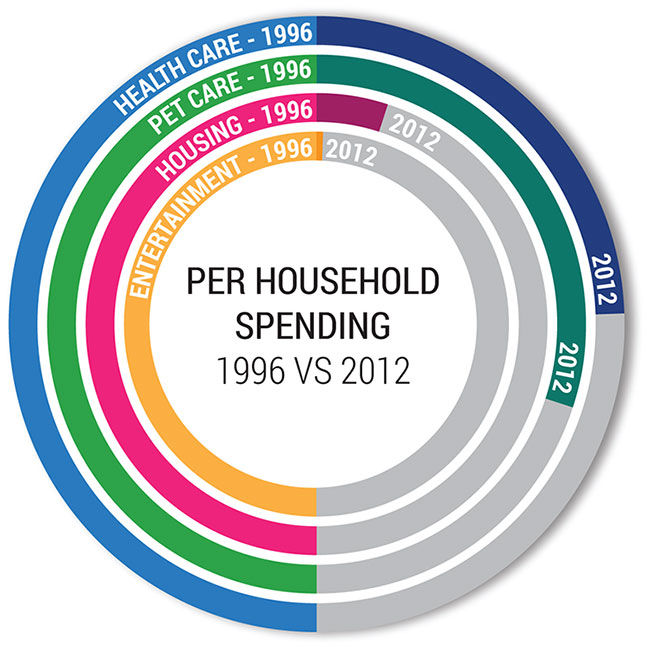

Figure 1. Pet care spending increased more than health care spending 1996-2012

This visualization reflects annual out-of-pocket spending per household in four spending categories using Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) data between 1996-2012. Growth in spending on pets surpassed spending in other industries.

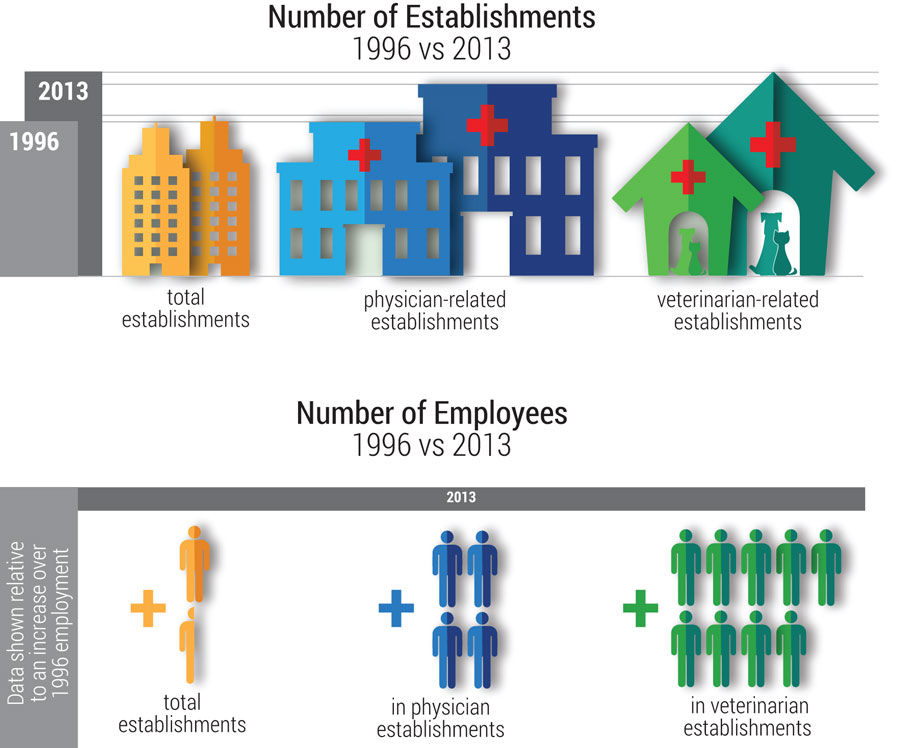

Figure 2. Veterinarian and related services grew faster than physician and physician-related services

Comparison of veterinarian and veterinarian-related services and physician and physician-related services reflects remarkable growth in employment and establishment of businesses compared to other industries. Country Business Patterns (CBP) data between 1996-2013 show that employment and establishment growth were similar among human and pet care, with physicians growing 40% and vets nearly doubling over the same period, with the other two industries once again remaining flat.

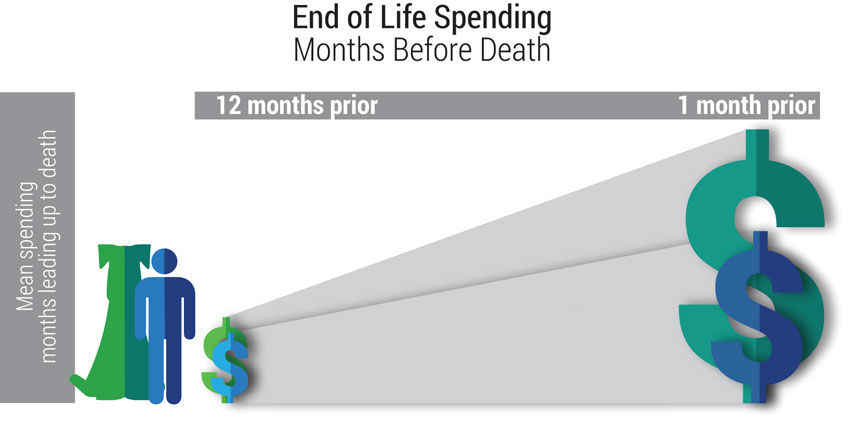

Figure 3. People spend lots of money for loved ones at the end of life

The above figure differentiates the emotionally charged decisions of both pet and human health care consumers, by highlighting the spike in spending for end-of-life care among lymphoma-diagnosed dogs and lymphoma diagnosed Medicare beneficiaries. The authors muse that the heart of complexity is in the nature of health care decisions: “Trading off potential health improvements against money—may make coldly rational cost-benefit decisions unlikely.”

Accelerate Editorial Team

Patients will ask three things of us over the next decade of health care improvement: help me live my best life, make being a patient easier, and make care affordable. To meet those needs health care must shift—from organizing around a patient’s biology to understanding the patient’s biography.

Sometimes the most impactful change comes from simply asking, “Why are we doing things this way?” Pediatric infectious disease professor Adam Hersh explains the impact of practice inertia on antibiotic treatment in pediatric patients, and how questioning the status quo improved outcomes and reduced cost.

Utah’s Chief Medical Quality Officer Bob Pendleton describes a strategic challenge faced by many industries, including health care. We are at risk for prioritizing achievement of metrics over our purpose. He challenges us to think beyond metrics to what patients actually need from us: patient-centered, outcome-focused, affordable care.