Friday, March 13, 2020, our medical students attended classroom sessions and rotated in our clinical environments. Three days later, all in-person educational experiences had been halted. This monumental shift required collaboration, rapid adaptation and innovation to continue educating future care providers under completely new conditions.

"The struggle you're in today is developing the strength you need for tomorrow. Don't give up." –Robert Tew

We moved courses and clerkships online by applying a patient-centered care model focused on listening to your patient and systematic thinking. Here are three key points we learned during the process.

#1: Listen to your patient (or student, or client, etc.)

Understanding the perspectives of people we serve is paramount for successful interventions. Without knowing a patient's values, feelings, and environmental and social challenges, a team is unable to adequately create solutions that meaningfully and wholly address the problem. With that in mind, we surveyed a broad spectrum of people impacted by the pandemic in the MD program (students, faculty, and staff); each voice was treated equally. Each group rated if communication, sense of community, resources, and wellness were lacking, adequate, or exceptional, along with providing comments for us to understand the “why” of any low rating.

#2: Develop a model for problem-solving

Health care providers rely on SOAP notes to guide and organize the care of patients: Subjective: what the patient is saying; Objective: the patient's vitals and physical exam findings (which can include other measurable items, like lab and imaging results); Assessment/ Plan: what our working diagnoses are, and how we plan to help diagnose and treat the problem. In other words, how do we interpret the patient's information and find a solution that would be value-added? We realized this SOAP framework could also guide our work as educators.

S-Subjective: We aggregated the survey data to understand stakeholders' perspectives for the key areas of communication, sense of community, resources, and wellness.

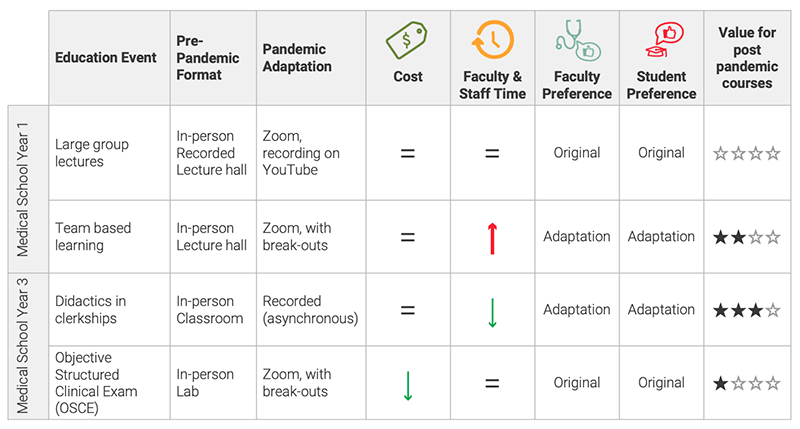

O-Objective: We adapted the U of U Health Value Driven Outcomes framework to gather objective data. This framework tracks costs and patient outcomes with data visualization to improve overall patient care with the patient as the unit of analysis.1 We applied the framework to all of the course/clerkship changes we made due to the pandemic.

Education Value = Time + Cost + Faculty Preference + Student Preference

| Variable | Action |

|---|---|

|

Time: |

Faculty indicated the time required (more, less, the same) for each education adaptation due to COVID-19 relative to the original pre-pandemic version |

| Cost: | Faculty indicated the cost (more, less, the same) for each education adaptation due to COVID-19 relative to the original pre-pandemic version |

|

Faculty Preference: |

Faculty indicated their preference for each education adaptation due to COVID-19 relative to the original pre-pandemic version |

| Student Preference: | Student preference for original pre-pandemic version vs. adapted was determined with a 70% majority threshold |

An overall value determination (high, moderate, low, or no added value) was based on the total number of metrics (cost, time, course director preference, student preference) favoring the adapted version.

See below for 4 examples:

A-Assessment, P-Plan: Combining survey and value data helped us to be responsive and efficient in the long-term. Specifically, as we went forward, the value outcomes from Spring 2020 adaptations served as "vital signs" for faculty leading Fall 2020 courses.

Faculty used the information to focus their courses, much like focusing on the patient interview, diagnosing problems, and finding solutions.

#3: Struggle can make us stronger

Responding to a disaster can improve our planning for future crises.

Just as clinical providers were required to maintain patient quality despite crushing adversity, educators needed to innovate, instead of "going into survival mode" during the pandemic. We recognized the need to help our students, staff, and faculty find ways to deliver excellent education or patient care despite a pandemic. Timely stakeholder feedback helped us get real-time information about whether we needed to continue to alter our curriculum, online assessments, or technology.

If we had not been forced to adapt, many positive changes would not have been made so rapidly. We now have built-in mechanisms to adapt quickly in case of other unexpected, future events that limit in-person meetings (earthquakes, fires, illness, etc.).

Reference

1. Kawamoto K, Martin CJ, Williams K, Ming-Chieh T, Park CG, Hunter C. et al. Value driven outcomes (VDO): a pragmatic, modular, and extensible software framework for understanding and improving health care costs and outcomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015; 22: 223-235.

Marlana Li

Tiffany Weber

Pete Hannon

Ibrahim Hammad

Brian Good

Rachel Bonnett

Candace Chow

Sara Lamb

Jorie Colbert-Getz

Your gut tells you a process could be better than it is—how do you back that feeling up with hard data? Senior value engineer Luca Boi shows how undertaking a baseline analysis can jumpstart your improvement project.

Why do some organizations thrive during a crisis while others flounder? Iona Thraen, director of patient safety, joined forces with her ARUP Laboratory colleagues to learn how the world-renowned national reference lab adapted to the pandemic. Leaders created a culture of safety by putting innovation, learning, and patient-centered care at the heart of all their efforts.

Patients will ask three things of us over the next decade of health care improvement: help me live my best life, make being a patient easier, and make care affordable. To meet those needs health care must shift—from organizing around a patient’s biology to understanding the patient’s biography.