Learning Objectives

After reading this article you will be able to

(1) Explain what active learning is and why it is important

(2) Describe different types of active learning techniques

(3) Incorporate active learning techniques in teaching sessions

Case Studies

Roni wants learners to have deeper understanding of QI concepts.

Roni is an emergency medicine physician with expertise in quality improvement. She is responsible for teaching fellows how to conduct QI projects. She is giving a lecture on “how to review QI manuscripts.” She has noticed that it is more difficult to gauge how well learners understand the material over Zoom. How can Roni ensure learners stay engaged during the presentation so that they can best assimilate and retain new information?

Alex wants learners to improve their difficult conversation skills. Alex is a fellow in child abuse pediatrics. He is involved in teaching trainees how to evaluate and manage suspected cases of child abuse or neglect. When child abuse or neglect is suspected, physicians must communicate their concerns with the family. This can be a difficult conversation to have. Alex wants to create an interactive session that teaches those skills. How can he best accomplish this?

Elizabeth Barkley describes student engagement as “the product of motivation and active learning” (Fig. 1).1 There is a synergistic relationship between these two elements; a motivated learner is more likely to make the most of active learning modalities. Although both motivation and active learning are key ingredients, considering each independently can help target strategies for improvement. We will focus our discussion on the benefits of active learning and versatile techniques that can be implemented for any teaching session.

What is active learning and why is it important?

Definition:

Active learning is an instructional method that engages students in the learning process.

Why does it matter? It improves knowledge retention, deepens understanding and encourages self-directed learning.

Active learning is an instructional method that engages students in the learning process. Students are required to participate in meaningful learning activities and think about the things they are doing.2 This is in contrast to traditional lectures where learners passively receive information from the instructor. Active learning is superior to traditional lectures for the following reasons.

Improves knowledge retention.

Typical adult learner attention span decreases after 15 to 20 minutes.2,3 Therefore, a traditional lecture is unlikely to be effective after this period. Identifying opportunities for engagement can facilitate both assimilation and retention of new information.2

Achieves deeper understanding.

Traditional lectures typically target basic levels of learning which includes memorization of facts. Active learning facilitates the application of knowledge or skills, which promotes the achievement of higher levels of learning on Bloom’s taxonomy.4

Encourages self-directed learning.

By being engaged in the learning process, students are more likely to seek out opportunities to learn independently.5

What are examples of active learning strategies?

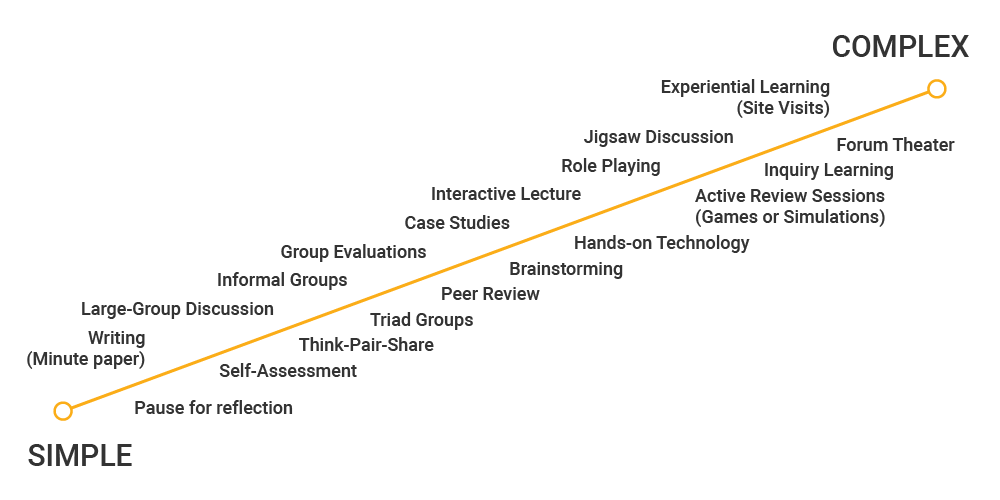

There are many types of active learning techniques. Some are simple and require minimal preparation; others are complex and require more extensive preparation (Fig. 2). Lower complexity techniques are not necessarily less effective; they can be very effective at engaging students, especially when teaching larger groups. All of these techniques can be adapted for virtual learning. Let’s explore them in more detail (Tables 1-3).

Active Learning Techniques

Lower Complexity Techniques

Definition: Pose a question to the group related to the information that was just presented and ask them to write down their responses. This is a type of “pause procedure” or breaks in a session to allow learners to clarify and assimilate information.

Example: After discussing causes of pediatric fever and rash, learners list most common etiologies before moving onto the next section.

Virtual adaptation: Audience response systems are great for “pause procedures.” There are many free resources.

-

Polling feature in Zoom

Definition: A type of “pause procedure” where learners reflect on and share areas of confusion.

Example: After discussing etiologies of pediatric fever and rash, ask learners to share what they still have questions about.

Virtual adaptation: Same as above

Definition: Learners reflect on a question, pair with each other to share their answers, and then share in a large group.

Example:

- Think: After discussing etiologies of pediatric fever and rash, ask learners to individually consider what laboratory evaluation they would perform.

- Pair: Learners partner with each other to compare responses.

- Share: Instructor calls on random pairs to share with the whole group.

- Video example

Virtual adaptation: Use breakout rooms in Zoom to group students during the “pair” portion of the Think-Pair-Share.

Medium Complexity Techniques

Definition: Usage of vignettes of patient encounters to facilitate a discussion.

Example: Instructor presents different cases of pediatric patients presenting with fever and rash to facilitate discussion about the evaluation and management of this chief complaint.

Definition: Learners act out part of a particular viewpoint to better understand the concepts and theories being discussed. This is useful for practicing physical exam or advanced interviewing skills.

Example: Learners practice taking history from parents with concern that their child has fever and rash.

Higher Complexity Techniques

Definition: Case-based learning in small groups

Example:

- Case assignment: Assign case of a 5-year-old girl presenting with fever and rash to the group.

- Identify knowledge gaps: During the first session, learners discuss the evaluation and management of this patient and identify additional information needed to address the case (e.g., common etiologies of fever and rash based on age).

- Address knowledge gaps: Prior to the next session, group members address knowledge gaps that were identified through self-directed learning.

- Complete case: Learners complete the case with information they have gathered.

Definiton: Small-group learning that involves pre-class material so learners are ready to learn. During class, learners are tested on the pre-class material and then work as a team to apply core content to scenarios. This works great in a flipped classroom model.

Example:

- Pre-class work: Learners complete pre-class material on pediatric fever and rash.

- Readiness assurance test: At the start of the session, learners complete a multiple-choice exam to ensure their readiness to apply this knowledge. Learners split into teams of 5-7 to re-take the exam. They turn in their consensus answers for immediate feedback.

- Collaborative work: Each team works through a series of cases on patients of different ages presenting with fever and rash.

Definition: A topic is divided into several smaller, interrelated pieces (i.e., subtopics). Each learner is assigned to read and become an expert on that subtopic. After each person has become an expert, they teach their team members about their piece.

Example:

- Assign subtopics: Each learner is assigned a common etiology of pediatric fever and rash (e.g., scarlet fever, hand-foot-mouth disease, etc.)

- Expert groups: Learners with the same subtopic will work together to fill in knowledge gaps. For example, learners assigned scarlet fever will work together to become experts on this subtopic.

- Team teach: Once learners have mastered their subtopics, they will return to their original group and teach other members of their group the subtopic they were assigned.

- Video Example

Above techniques modified from Wolff M et al. Not another boring lecture: Engaging learners with active learning techniques. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(1):85-93.

How do I choose which technique to incorporate?

Desired learning outcome

It is essential to align the desired outcome of a teaching session (i.e., learning objectives) with the appropriate active learning strategies. Learner engagement should not be the sole desired outcome. For example, role-play is useful for learning interviewing skills. It is less effective for understanding the pathophysiology of congenital heart disease.

Learners’ level

Determining learners' baseline knowledge or interest via a pre-survey can help guide all aspects of a teaching session, including which active learning techniques to incorporate.

Preparation

While some active learning strategies can be easily incorporated into existing lectures (e.g., pause procedures), others will require more time-intensive modification.

Trial and error

Although a well-designed teaching session can be accomplished through careful planning and preparation, don’t be afraid to try something new! Like any skill, teaching using active learning techniques can be honed through practice.

Conclusion

Let’s return to our cases.

Roni incorporated pause procedures for deeper understanding.

Roni included “breaks” throughout her teaching session to check learners’ understanding before moving onto the next section. She used the polling feature in Zoom to identify areas of confusion. Because of this, learners were more engaged and were able to gain deeper understanding of QI concepts.

Alex used role-play to improve communications skills.

Learners practiced interviewing skills by taking turns role playing either the health provider or parents in a pre-crafted scenario. After the role-play, Alex debriefed with trainees and filled in any gaps in knowledge or skills. Learners felt this was an excellent way to stay engaged during the session and practice those difficult conversation skills.

References

- Barkley, E. F. (2010). Student engagement techniques: A handbook for college professors. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93, 223-231.

- Cooper, A. Z., & Richards, J. B. (2017). Lectures for Adult Learners: Breaking Old Habits in Graduate Medical Education. The American journal of medicine, 130(3), 376–381.

- Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. Active Learning.

- Wolff, M., Wagner, M. J., Poznanski, S., Schiller, J., & Santen, S. (2015). Not another boring lecture: engaging learners with active learning techniques. The Journal of emergency medicine, 48(1), 85–93.

*Originally posted Mar. 11, 2021

Cheryl Yang

Academic medicine has been thrown into the brave new world of virtual communication, instruction and online learning. Pediatric endocrinologist and clinician educator Kathleen Timme shares a process to transition from traditional training to meaningful and engaging.

Hospitalist and Graduate Medical Education director of quality and safety Ryan Murphy explains how Accelerate’s playlists are an infinitely modifiable, curiosity-satiating approach to unifying learners behind a single vision. With more than 15,000 visitors in the last 12 months, it’s worth taking a look.

Being new is hard. Often for new faculty, it means adjusting to a new state, new team, new patients, and a new organizational culture. We asked hospitalists Ryan Murphy and Valerie Vaughn and surgeon Ellen Morrow for tips that only come from a little time under the belt.