was sick as a kid. I was born with heart defects, a VSD (ventricular septal defect), and an ASD (atrial septal defect). I was pretty fragile and sickly. I was completely at home and didn’t go to school until 5th grade. My mom homeschooled me. She was a kindergarten teacher, and we had teachers come to the house. That was my normal—I didn't know any different.

Since I wasn't out playing football with the kids in my neighborhood, I got really into science. I had extensive chemistry sets that I ordered out of books. That ended, though, when I got a book on building solid fuel propellant rockets. My dad said, "I don't think we're going do that."

When I was 11, everything changed. I had open-heart surgery performed by world-famous heart surgeon Denton Cooley. As a kid, you idolize people who help you out. Cooley came in as this galloping knight and changed my life forever. This idea that you could alter the course of someone’s life for the better led me into medicine.

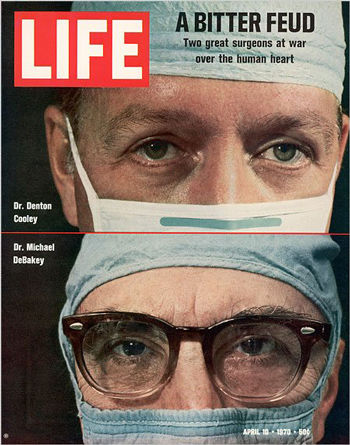

Denton Cooley was outstanding—one of the most famous heart surgeons in the world. The heart-lung machine was invented in the 1950s, which allowed open-heart surgery. It was the beginning of the golden era of cardiac surgery, and Cooley was incredibly proficient. He had an international reputation as one of the best surgeons in the world. He trained at John Hopkins and came to Texas in 1951 when Michael DeBakey hired him at Baylor College of Medicine.

The cardiac kings—and their 40-year feud

DeBakey was the other great name in heart surgery in those days—he helped develop the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) during World War II and the Veteran’s Administration medical system in the 1950s. DeBakey and Cooley pioneered both coronary bypass surgery and open-heart defect surgery, but then they had a big falling out, as two big egos always do. Around 1960, Cooley moved his surgical practice to St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, where he established the Texas Heart Institute.

Cooley performed the first successful heart transplant in the US in 1968 and the first transplant with a Total Artificial Heart (TAH) in 1969. He worked on the TAH device with Domingo Liotta, who first started developing it under DeBakey’s supervision at Baylor. DeBakey didn’t think the TAH was suitable for humans, though, so when he found out about Liotta and Cooley’s use of the device, he ripped it in the press and claimed it broke federal rules. DeBakey filed several complaints against Cooley, who was censured by the American College of Surgeons and forced to resign from his faculty position at Baylor.

The two heart surgery pioneers didn’t speak to each other again until 2007, when DeBakey received a Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award. A few days later, Cooley organized a ceremony to give DeBakey a lifetime achievement award from the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society.

“The Walmart of heart surgery”

Cooley was a tall, athletic, good-looking guy—he lettered for the University of Texas basketball team when he was in college. He had an international reputation as one of the best training surgeons in the world. We talk about efficiency as this modern development, but Cooley was on the forefront. He had eight or nine ORs going at the same time. They would just stack the rooms, and he would go from room to room to room—do the open-heart surgery, close the patient, and move on.

I think my dad figured out that the guy was probably taking home $1,000 a case, times nine or ten a day. That's in 1965 in Texas. Eventually, Cooley became a multi-millionaire, investing heavily in the Texas real estate market with Governor John Connally, who was in the car with President John F. Kennedy the day of his assassination. The housing market turned upside down in the late '60s, though, and Cooley lost a fortune.

Ultimately, Cooley was changing kids’ lives. I was an example. After my heart surgery, I grew like a weed. I was finally able to play competitive sports, something I've loved my whole life. But after spending so much time at home, I also became a hellion. I got all kinds of unsatisfactory conducts on my report card. My dad was always saying, “How come we didn't get a two-fer for brain surgery? Can't you do something about his brain?”

Remember your touchstone

Later on, as a family, we watched my mom go through a very prolonged and awful death due to bilateral breast cancer. She had a difficult downhill course and passed away when I was 15. My surgery plus her death were on my mind when I decided to go into medicine. On the one hand, Cooley saved my life. On the other hand, I knew there was still plenty of work to do because my mother died of this awful, terrible, debilitating disease.

No matter where you are in your career, you always need a touchstone. Why are you doing what you do? Are you trying to make the world better? At the end of the day, this work is difficult. You make mistakes; people get pissed. You’re always on the edge of the diving board. You go home and think, “Why am I doing this? This is such a drag.” You have to be able to say, “I’m doing this for a reason—and over time, I’m making a difference.”

Liberal arts for medicine

Tom Miller loves literature. As he recently said about the Physicians, Literature, and Medicine discussion group, “We go into medicine with the intent to heal and help others through difficult situations, and literature helps us navigate tough, sorrowful issues. Discussing the connections is instructive.”

For those who love to read, we asked for a short list of Tom's favorite reads:

- Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner

- The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Anything about Winston Churchill

“When you're down, you go, ‘How am I ever going to get this done?’” Miller says. “Things seem so complicated. Then you read something about Winston Churchill and think, ‘Nothing in my day is anywhere close to that.’"

Tom Miller

We’ve all done it: attended an amazing lecture or conference and gleaned some great ideas, only to return to work and forget about it entirely a couple weeks later. This common conundrum prompted Lawrence Marsco to ask the U of U Health LDI curriculum committee, “How do we know if anyone’s using this content?”

How can physicians move toward an alternative mode of scholarship — one that’s still scientifically rigorous and peer reviewed but communicated in a more accessible manner? Cardiothoracic surgeon Tom Varghese is building this kind of non-traditional path.

Health care is made up of people — creative, passionate people with big ideas who are often too busy to learn from one another.