Safety is personal

e talk a lot about patient safety in the health care field, and for good reason. The real-world consequences of getting it wrong can be devastating for patients and their families. For me, patient safety is personal, and there are two experiences that illustrate how it can go wrong or right.

First the scenario that went wrong: About eight years ago, my father fractured his hip and as a result of his hospitalization, contracted hospital-associated pneumonia and had to go to an ICU. He began recovering, but then my mother, who was fully functional and living independently, through her exposure to him also contracted pneumonia. Doctors couldn’t figure out what was going on, and even with my brother as a live-in caregiver, she continued to decline.

Nobody realized she had been exposed to a hospital-associated infection, and the emergency department in the same hospital where my father was in ICU had no protocol in place for the identification and treatment of sepsis, and as a result she passed away just two days later. Subsequently, my father was allowed to pass away shortly thereafter. Everything that could have gone wrong in this scenario did go wrong.

While both of these experiences ended with the death of someone I love, the way I experienced them was dramatically different.

On the other hand with the same outcome of death, here is a scenario where everything went right: Many years earlier, my 50-year-old brother—a helicopter instructor we affectionately called “Mountain Man Mike”—suffered a brain aneurysm. Found slumped over a workout bench, he was revived and taken to the local hospital. At the hospital, he was placed on life support and kept alive long enough for family to gather from four different states. The doctors explained to our family that the aneurysm was in the back of his brain, so there was little hope of recovery. His living will specified that he did not want to be kept alive, so the physician explained what would happen to my parents and helped them come to terms with letting him pass. Despite navigating all the challenges that came with a family unexpectedly losing a loved one, and a brand new law about patient privacy (HIPAA had just come out) and an outcome of death, the health care system in Colorado Springs did everything right.

While both of these experiences ended with the death of someone I love, the way I experienced them was dramatically different. One experience was fraught with errors while the other one went exactly as it should. To me, this illustrates the differences between a reactive and a proactive approach to safety.

Moving from reactive to proactive patient safety: an evolution

The first stage in our safety journey—I call it Safety 1.0—has been to improve the use of technology while addressing human factors. Safety has always been important, but it’s addressed reactively by reviewing what happened and figuring out after the fact what went wrong. While we can learn from this information, if we don’t take the next step, we will always be reactive in our approach.

As we progress in our understanding of Patient Safety (Safety 2.0), in addition to identifying what we do wrong, we use all the information at our disposal to find out what we’re doing well and disseminate those findings as standardized best practices to the entire organization. This allows every department to replicate what works with information that can be duplicated, evaluated, and improved over time.

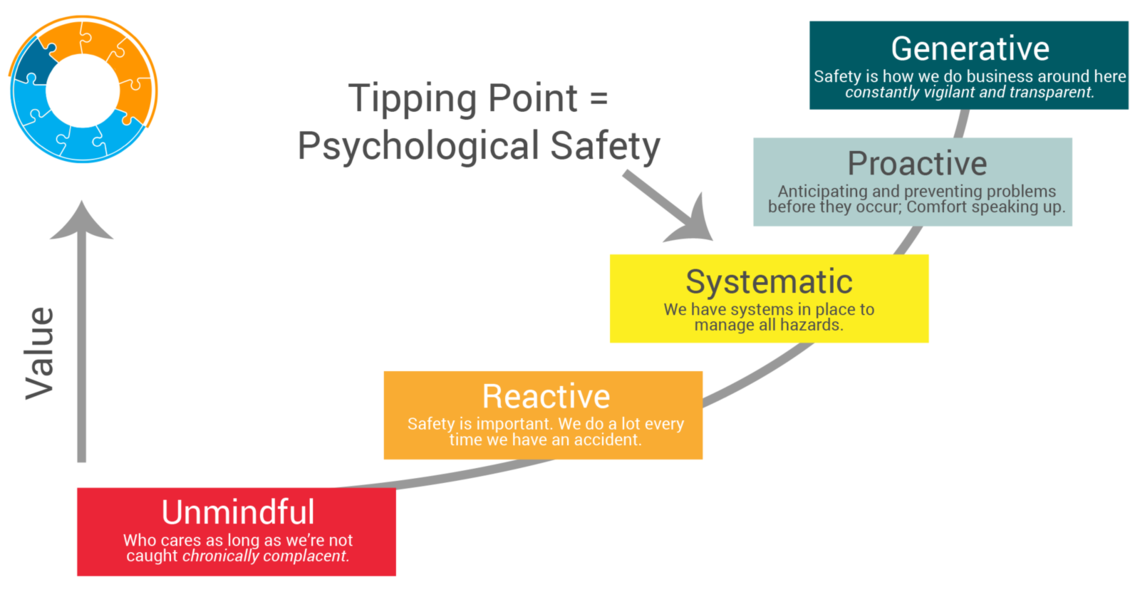

There is a continuum of safety within organizations that ranges from Unmindful to Generative. I believe the tipping point between Systematic and Proactive is where we achieve psychological safety. While it’s good to have systems in place that will manage issues as they come up, it’s even better if we can anticipate problems before they occur and avoid them whenever possible.

Safe and Reliable Culture Maturity Model

Our progress

We have accomplished a lot so far on our safety journey which includes:

- A Reporting Infrastructure: we successfully implemented reporting mechanisms to collect feedback from anywhere in the organization.

- Governance: we have a working group called the Quality Council with a mission to create systematic classification of serious safety events that occur. We’re examining best practices from other organizations like Johns Hopkins and Yale to classify PSCs in a way that helps us address or prevent future problems.

- Data Analysis: we have conducted multiple root cause analyses (RCA²), are reviewing data streams throughout the organizations and have investigated multiple events using the 5 why’s with the goal of learning as much as we can about past safety events to inform and improve processes.

Where we go next

In my first six months here at U of U Health I took the opportunity to establish a baseline period where I did a lot of observation, conducted a SWOT analysis through participant interviews and discussions. I’ve also looked at multiple data streams and the literature around patient safety.

Our goal moving forward is to find ways to integrate various data sources that will align information coming from the safety reporting system with patient experience feedback, Safety Learning System information, as well as other sources. When something happens, we are not just checking that the issue was resolved, we’re also talking to different departments to find out what’s happening on a system level, learning when we need to get involved. The data can also be reviewed for patterns that could alert us to a potential problem before something serious happens so we can intervene earlier.

The goal is to move from siloed safety operations to a system of care where partnerships and collaboration become the norm, and where we can proactively push standardized best practices in safety out to the entire organization.

Safety as a value, not a priority

It might seem strange to say that we don’t want safety to be a priority at our health care facilities. When you call something a priority, the attention it gets will fluctuate based on other priorities and available resources. Instead, we want to incorporate safety as one of our core values. We want it to be ingrained in the way we do business and practice medicine.

Safety as a value requires a cultural shift, not just getting people to talk about patient safety but to know how it impacts everything we do. We want our team to continually be thinking about what safety behaviors will most benefit our patients, care providers, and employees.

We want to incorporate safety as one of our core values. We want it to be ingrained in the way we do business and practice medicine.

Cultural changes aren’t easy, but they are possible. I think about the cultural shift in our approach to sick days. People used to call you heroic for showing up to work even when you were sick, but we now know that when our employees are sick it can harm co-workers and patients. We experienced a cultural change that supports staying home when you’re sick because we recognized how that improves care.

We don’t have this all figured out yet, but University of Utah Health is leading the way in making patient safety an organizational value. We are using data to improve systems and processes, giving every employee an effective way to report what is happening, and translating that into proactive and actionable best practices that we can use in every department to improve patient safety.

*Originally published March 2020

Iona Thraen

The practice of medicine is recognized as a high-risk, error-prone environment. Anesthesiologist Candice Morrissey and internist and hospitalist Peter Yarbrough help us understand the importance of building a supportive, no-blame culture of safety.

For National Injury Prevention Day, Spencer Steinbach, Senior Nursing Director, discusses safety and injury prevention in nursing and the outdoors and shares tips for your next adventure.

What does it mean to take a system approach to problems? The discipline to learn as a team, patience to wade through hundreds of cases, and a diversity of perspectives. Utah’s Critical Care Senior Nursing Director Colleen Connelly, System Quality, Patient Safety, and Value Senior Director Sandi Gulbransen, and Associate Chief Medical Quality Officer Kencee Graves reflect on what they’ve learned by studying system problems with an interdisciplinary team.