Intimate Partner Violence Resources

National Domestic Violence Hotline:

Call 800-799-SAFE (7233)

Text "START" to 8878

Visit thehotline.org to chat LIVE

National Sexual Assault Hotline:

Call 800-656-HOPE (4673)

Visit online.rainn.org to chat LIVE

Utah Domestic Violence Coalition:

Call 800-897-5465

Visit udvc.org for local resources

Shelter locations in Utah:

stoptheviolenceutah.org

ntimate partner violence (IPV), rape, and sexual assault are not easy topics to discuss. They are deeply stigmatized in society, both for victims and perpetrators of violence. It can be a tricky tightrope, but understanding how best to talk about it can enhance the ability to help victims, while at the same time hold perpetrators accountable for their abusive behaviors.

One of the reasons that this is such a difficult topic is society’s general attitudes and discomfort with sex and sexuality. Even getting someone to say the words ‘penis’ and ‘vagina’ (anatomically correct descriptions of sex) can be uncomfortable for many people.

If people are not comfortable talking about sex in a clinical or educational setting, it becomes harder to talk about when the discussion makes you insecure, vulnerable, or defensive. But the ramifications of sexual violence and IPV can last for decades, even as broken bones heal and scars from physical violence fade.

No matter how long ago it was, a traumatic experience like rape, IPV, or sexual assault can take away a person’s sense of safety. That constant state of fear and worry after being hurt or violated can lead to risky behaviors—including criminal behaviors—that can be harmful to a person’s life and health.

Positive approaches

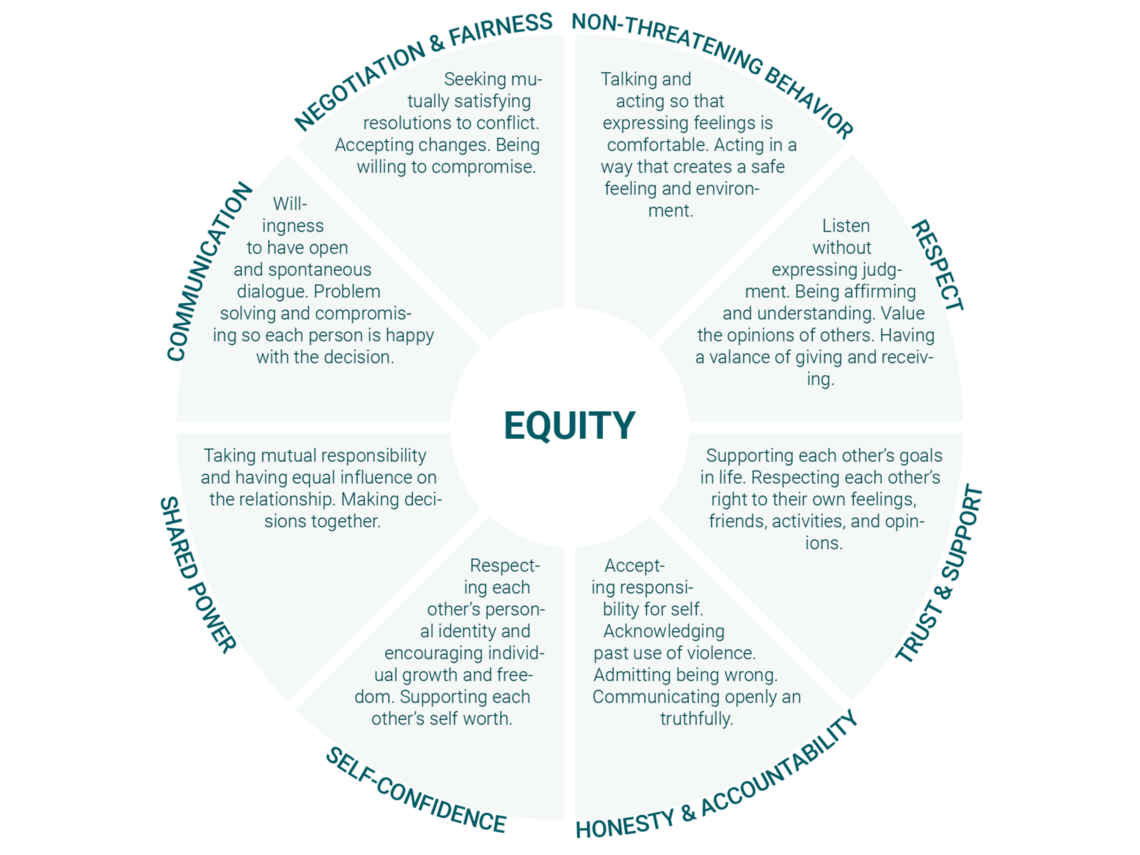

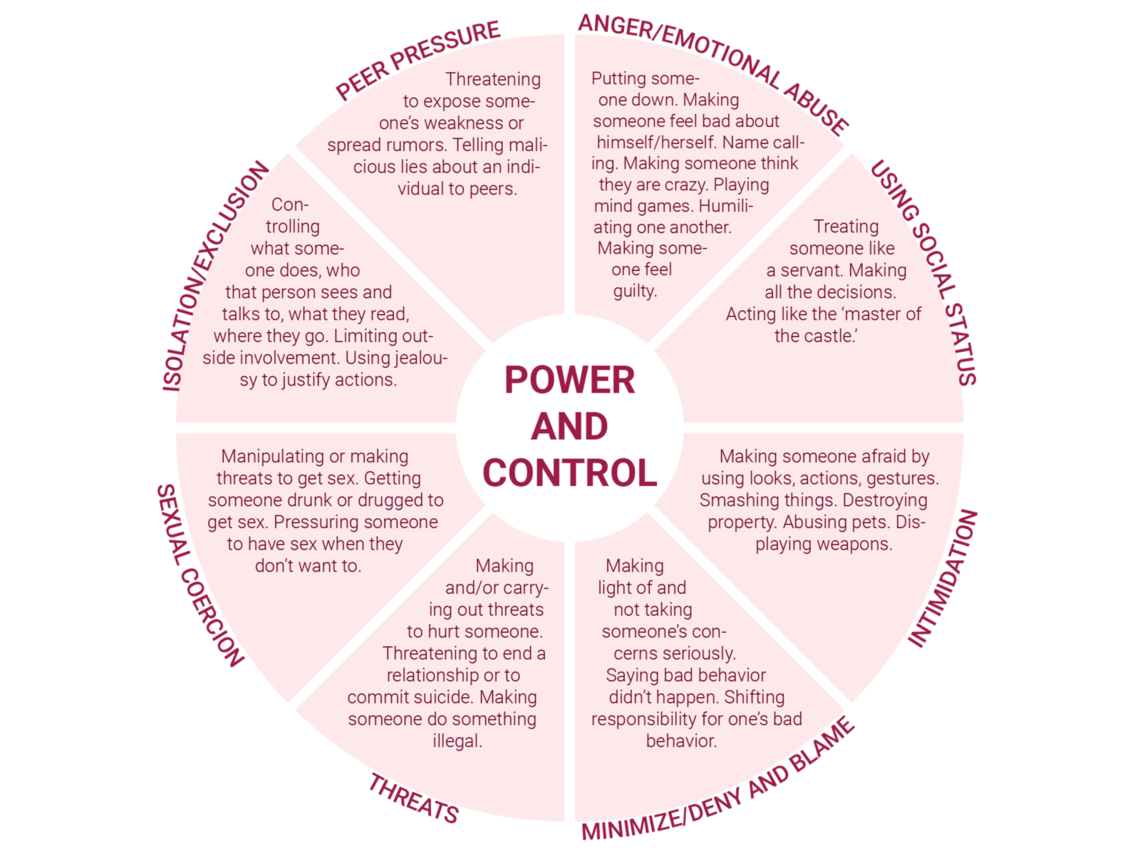

Healthy vs. unhealthy relationships

The first step to help someone who experienced IPV is to take away the labels that stigmatize or shame. Categorizing behaviors as right or wrong, good or bad, can increase those feelings. Instead, helping people understand behaviors as being healthy or unhealthy, can impact a person’s health and well-being across the lifespan.

It’s also important for people to recognize unhealthy and healthy behaviors in relationships so they can spot risks or red flags in current or future partners.

Healthy relationships

Unhealthy relationships

Strengths-based

Most people don’t like to be told they are wrong. Focusing on the positive with a strengths-based approach helps someone see what they are doing well so they can enhance those things that improve overall health and well-being.

A critical, and sometimes forgotten, piece of the puzzle to end IPV is engaging with men. Men are far more likely to be the perpetrators of violence against women—it’s not always the case, but it is by far the most common. We can tell men to stop doing things that are harmful, but we shouldn’t stop there. We should also give them information about how they can do better—what they should do and how to do it, instead of just what they shouldn’t do.

Social norms

Social norms are the values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that reflect a group of people or a culture. They can be both good and bad. They can also change over time. Most of us will do the right thing when given a chance, but sometimes it requires education around societal norms that encourage unhealthy behaviors. Peer pressure can be a powerful influence in cajoling someone into doing behaviors or actions that they know are harmful and wrong.

Misperceptions about social norms or what is acceptable can also make people behave in ways they otherwise would not. For example, victims are often held accountable for a rapist’s sexual violence by focusing on what they were wearing, how much they had to drink, or why they put themselves in these risky situations. Misperceptions of holding the victim accountable have persisted for centuries and further compounds the negative impact that trauma has on an individual.

Changing social norms around the willingness to discuss IPV and sexual violence can change people’s behaviors and beliefs because most people’s inherent beliefs are more in line with sexual violence prevention goals.

Bystander intervention

One of the best approaches to primary prevention of IPV is bystander intervention. This teaches people how to intervene when they see abusive, harmful, or negative behaviors or actions. The misperception that this is ‘none of our business’ further prevents perpetrators from being held accountable and victims from healing. Bystander education has been shown reduce to violence. This education provides tools to know how to effectively intervene in a safe way.

Focus on the meaning, not what happened

Most people who have had traumatic experiences do not see themselves as victims. Therefore, the language that is used when talking about IPV is important. Rather than focusing on what happened to someone as a victim, shift the focus to what they have overcome as a survivor, and who they are as a person beyond the abuse.

Be kind to build resilience

Intimate partner violence, rape, and sexual assault are hard topics to discuss. We need to be kinder in our approach when working through these difficult issues.

The first step is to be educated about the power and control dynamics in IPV relationships which may challenge previously held beliefs and attitudes. Understanding these concepts begins the process of changing unhealthy societal norms.

The conversations are not easy. They must be carefully navigated to allow people the chance to be vulnerable and build resilience, both of which are skills that are built, developed, and honed over time.

Kathy Franchek-Roa

Marty Liccardo

Dentist Gary Lowder has spent the past 36 years working with patients who suffer from jaw disorders that result in chronic pain. As faculty in the School of Dentistry, he’s passing along the power of vulnerability as a patient trust-building exercise with his trainees.

Chief Wellness Officer Amy Locke shares practical strategies for leaders to address the real tension we’re feeling between the desire to take a break and the increasing workload.

How do I share employee engagement feedback with my team? Chief Wellness Officer Amy Locke, Resiliency Center director Megan Call, Utah Health Academics HR leader Sarah Wilson, and Organizational Development Director Chris Fairbank explain when and how to talk with your team.