About this series:

Beauty in a Broken World is a collection of essays, poems, music, photography and spoken word generously contributed by a Harvard Divinity School student cohort led by author and Utah native Terry Tempest Williams, to bring solace and solidarity during the coronovirus pandemic.

ately I’ve been thinking about Anne Carson’s essay Kinds of Water because her observations of pilgrimage struck a chord with me. She gets her title from a line on about the third page of the essay, “Kinds of water drown us. Kinds of water do not.” This simple observation, that water comes in kinds with different functions, some wonderful, some hazardous, is an observation a pilgrim would make that a settler might not. If you ask most people in Cambridge about kinds of water, they’d first say “there’s only one kind,” then grudgingly admit that the sea contains something different.

On my pilgrimages on the Pacific Crest Trail, I have encountered at least four kinds of water. First, there is sustaining water—the little water hole in the desert that you would drink from at no other time, the garden hose from a cattle trough, the municipal tap sitting in the hot desert sun. It is water, you drink it (probably with a Nuun tablet in it to improve the taste), and you pray your filter is working. Since there are few water sources in the desert, everybody comes and congregates by them—they often look like a flea market with all the camps by some tiny water source.

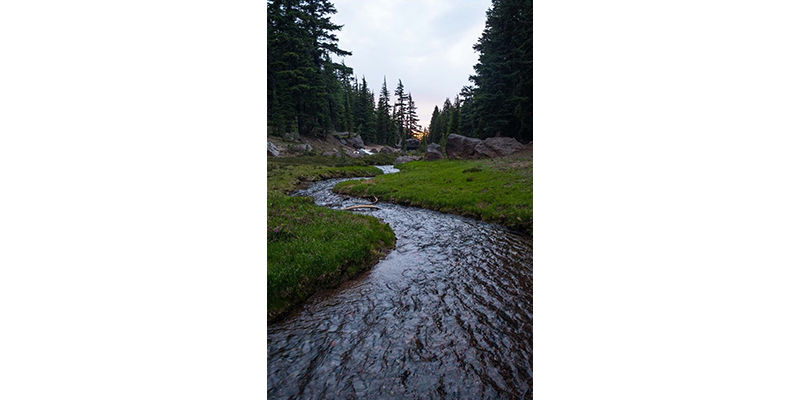

Second, there is peaceful, welcome water—I have seen it most in Oregon lakes—it’s much more drinkable than the desert variety—you still filter it, but you wonder what might happen (or not happen) if you didn’t. In addition to the lakes of Oregon, this peaceful water is found in the slower rivers along the trail. Unlike the desert water, which may or may not taste good, we need it to sustain our bodies, this is good water—it is wild water, free of the chemicals of industrial sources. Its sources bring peace to the landscape, there is always a feeling of balance by a lake or a river, and these sources are abundant—peaceful water exists where the landscape has plenty of water for everyone.

The third kind of water is the exuberant mountain water. This is the pure ecstasy of the world. It comes in a fast flowing stream, in a spring from a rock, in a waterfall. Its taste is pure and beautiful—it is so cold that, even on a hot day, you may want to wait a bit before drinking it. There are few experiences like a liter of fresh mountain water straight out of the waterfall—it is cold, it is clear, it has the terroir of the local landscape. If you are really lucky, there is a berry bush growing right next to the waterfall, and you can wash handfuls of berries down with mountain water. Sometimes, there are enough sources of mountain water around that you never touch water you carry any distance—you drink a couple of liters at one waterfall, and you are just becoming thirsty at the next one. Just as I filter even mountain water, I always have a liter or two on my back just in case—but there are paradisiacal days when it is not needed. Mountain water is so exuberant as it dances into your bottle that you can’t help but get wet as you collect it. On a cool day, you try to stay as dry as possible, but on a hot day, you may embrace the mountain water—stick your head in the waterfall and rinse your hair, put your feet in the quick-flowing stream.

The final kind of water is when the mountain water gets too fast. Sometimes, in the season of snowmelt, a stream that barely flows for much of the year becomes a raging river. It can carry the bridge away, or scour a deep hole where a shallow crossing should be safe. Water gives life, but it can also take it away if we aren’t careful.

All photographs were taken by Dan "Shutterbug" Wells, permission granted for use in the "Beauty in a Broken World" healing U of U Health collaborative.

Terry Tempest Williams is a Utah native, writer, naturalist, activist, educator—and patient. She reflects on this moment on the threshold of what’s next as the country reopens in this last dispatch from the desert.

Terry Tempest Williams is a Utah native, writer, naturalist, activist, educator—and patient. She reflects on venturing out after 52 days and how we’re coping with nostalgia and the present.

Terry Tempest Williams is a Utah native, writer, naturalist, activist, educator—and patient. Terry answers and asks “How are we doing?” She wonders “what are we learning?”