What are adverse events?

ealth care workers face adverse events daily. These events include secondary trauma, occupational trauma, unexpected death or injury, moral injury, medical error and malpractice lawsuits. Frequent exposure to trauma, coupled with the unrelenting pressure of the pandemic, has left many workers struggling to recover.

People experiencing trauma often worry their reactions and feelings are abnormal or pathological. Without leadership and peer support, that self-doubt can trigger professional, institutional and personal breakdowns.

Professional impact: When workers feel isolated or unsupported after adverse events, they become more prone to medical errors, worse patient outcomes, and decreased patient satisfaction. Lack of confidence can also spiral into unprofessional or disruptive behaviors and compassion fatigue.

Institutional impact: Self-doubt drives people to question whether they can or want to continue working in their field. From a human capital perspective, that's an immense loss of investment in training, expertise and skills, and costs of recruitment and retention will increase.

Personal impact: The effects of traumatic experiences also extend beyond the workplace. Many people struggle with family disruption, anxiety and depression, substance abuse, and even suicidal thoughts.

Failure to respond to adverse events or trauma can lead to:

Health care workers often focus so much on patients’ welfare that they don't notice when their peers are struggling. While most people cope with significant stress without lasting trauma, some become injured or ill. Since they're so focused on helping others, our colleagues who do become ill or injured often avoid seeking professional help for themselves.

Co-workers have a unique opportunity to give informal support to prevent more significant problems. When necessary, they can be a bridge to more formal treatment.

When someone feels supported by their colleagues and managers after an adverse event, the risks of burnout on the team decreases, the unit engages in better teamwork, and the patient safety climate improves.

How adverse events lead to stress injury

Adverse events can trigger stress injuries in four different ways:

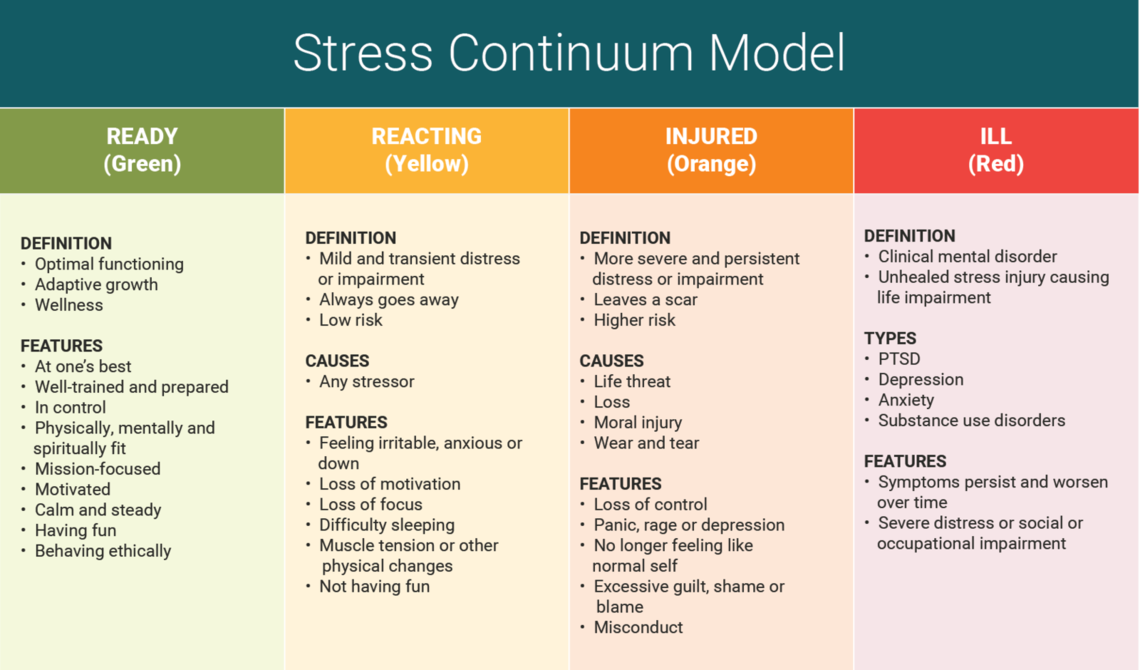

We conceptualize stress on a continuum that ranges from transient and mild to chronic and debilitating. Our model identifies four zones:

- Ready (Green): Someone in this zone feels in control, acts calmly and behaves ethically. They exhibit optimal functioning, growth and wellness.

- Reacting (Yellow): Someone in this zone often reacts to stress with irritability or anxiety. While they might struggle to focus or stay motivated, they’re capable of resolving their stressors.

- Injured (Orange): Individuals have undergone a life threat, loss, moral injury or wear and tear that caused severe distress or impairment. They may exhibit panic, rage or depression. They likely feel out of control, and experience intense, persistent feelings of shame or guilt.

- Ill (Red): People in this zone struggle with an unhealed stress injury that causes significant distress. They may suffer from clinical mental disorders, PTSD, substance abuse, and social or occupational impairment.

Most reactions are temporary

Remember, 100% of people react to stressful experiences. Responses fluctuate based on many factors, including how people prepare for and interpret adverse events. Symptoms may remain intense for two weeks following an incident, but usually stabilize after a month.

If recovery is thwarted, it causes harm to both clinicians and patients. Our culture of medicine doesn’t always facilitate individual recovery. In fact, health care often perpetuates a culture of stoicism, where workers sacrifice their own wellbeing to care for others. While we are working to overturn those expectations, change takes time.

As we continue to create an environment grounded in peer support, remember to have some compassion for yourself. Self-compassion helps us acknowledge our suffering, respond with warmth and caring, and understand that suffering is a shared human experience.

Instead of berating yourself, practice love, kindness and patience. Recognize that you can’t rush recovery, so check in with yourself and make sure to address your needs.

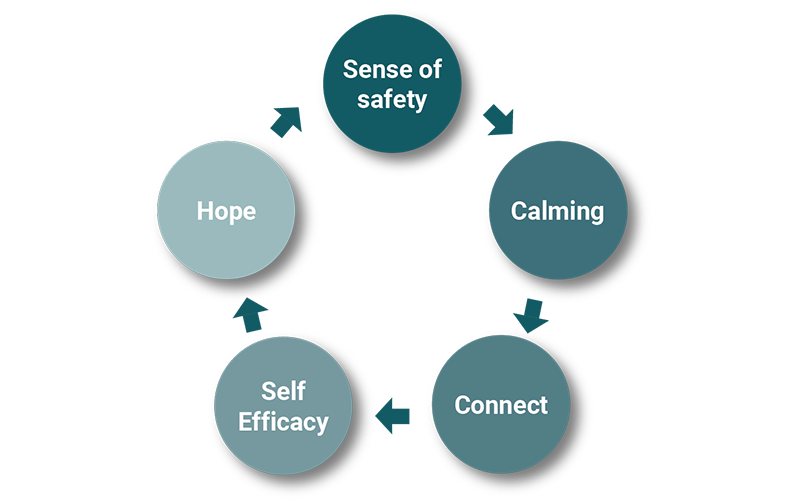

5 factors in recovery from adversity and stress

Reestablish physical and situational safety by assuring workers, “Hey, we’re going to figure this out as a team. This stuff happens all the time. Let’s use our M&M to identify how we can improve this process in the future.”

A little anxiety can be healthy, but excessive stimulation of the heart rate, blood pressure and respiration can cause disruptive sleep, dehydration, poor decision-making and other long-term health problems. We can restore our body’s resting state through physical activity, breathing exercises, positive social interaction, emotional expression, and creative endeavors.

Social connectedness is one of the strongest protective factors against stress injury and is linked to emotional well-being and recovery following traumatic experiences. People need different things at different stages of their recovery, so don’t be afraid to check in with them – not just right after an event – but also down the line.

Adverse events often shake people’s confidence in their ability to predict outcomes or perform at work. Managers, make sure to engage them in rewarding activities to help rebuild that confidence. People who believe they can overcome adversity are better equipped to handle stress, solve problems and recover in tough situations.

Through hope we can encourage optimism, spirituality, and faith that things will work out for the best. Leaders, restore hope by showing your workers their team still respects them. Remind them that you’re all in this together.

Peer support fundamentals

Try using these four fundamentals when supporting a struggling peer:

Simply listen: Don’t jump to problem-solving – trying to fix things isn’t always helpful. One of the core aspects of peer support is just listening.

Validate emotions: Reflect on what you hear, identify the person’s emotions and what’s being talked about, and validate their emotional experiences.

Check-in on coping strategies and support: If they seem comfortable, try to respectfully ask if they use any coping strategies or have additional support.

Provide resources: If they seem receptive, provide additional resources where they can find further support.

Keep in mind, validation is NOT about logic, arguments or solving problems. It’s about assuring them, “Yeah, it makes sense that you feel that way.” Validate your colleague’s emotions through empathetic listening and understanding.

U of U Health Peer Support

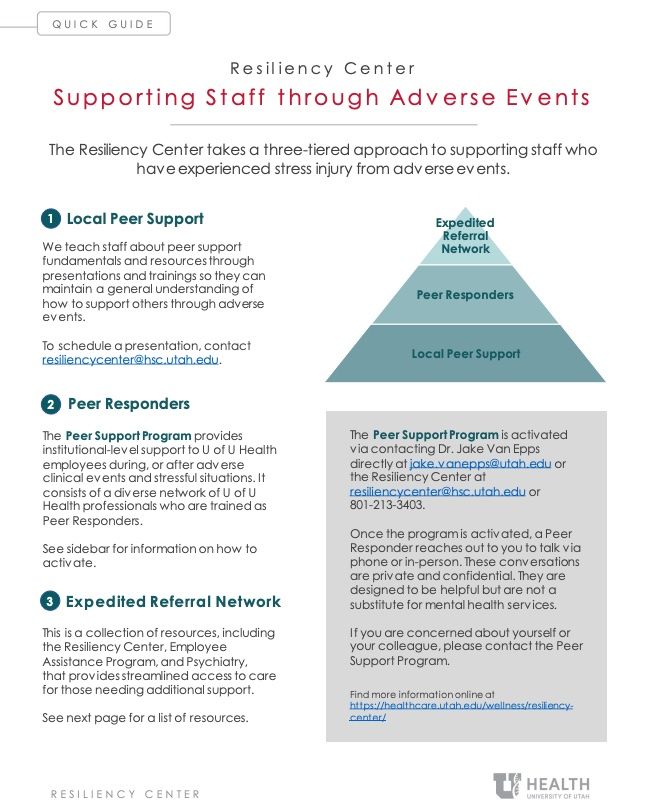

Here at U of U Health, we utilize a three-tiered approach to supporting peers after they’ve experienced adverse events.

The first tier is Local Peer Support. We teach as many people as possible the importance of listening to understand, not to fix, and the significance of validating emotions. We also provide our staff with additional resources to offer struggling colleagues.

Our second tier is the Peer Support Program, led by Peer Supporters who have gone through similar experiences and have received training in processing and coping with trauma. Workers often prefer to confide in Peer Supporters to avoid feeling judged or evaluated by direct colleagues.

The third tier, our Expedited Referral Network, is a collection of resources available to all employees. The collection includes The Resiliency Center, EAP and Psychiatry, and streamlines access to professional care for people who need support quickly.

For assistance navigating the peer support tiers, contact the Resiliency Center at resiliencycenter@hsc.utah.edu or 801-213-3403.

Originally published March 2022

Jake Van Epps

Creating psychological safety for your team is a process that takes time, vulnerability from you as a leader, and collaboration from others. Psychiatrists Jen O’Donohoe and Kristi Kleinschmit share 6 practical next steps for when psychological safety might be a little off on your team.

As our health care system continues to address pandemic-related employee burnout and fatigue, we can apply simple strategies to enhance our own recovery. Psychologist Megan Call and physical therapist Keith Roper return to a previous marathon analogy to share five recovery strategies for individuals and teams.

Chief Wellness Officer Amy Locke shares practical strategies for leaders to address the real tension we’re feeling between the desire to take a break and the increasing workload.