you’ve probably noticed, no one has yet figured out how to structure a health care system. No country, state, region, local municipality, business, etc. has determined how to organize a system to accomplish the (now) quadruple aim: better care, better outcomes, lower cost, and satisfied providers.

In light of this, I was looking for a different type of practice coming out of residency. As a family medicine physician, I feared the burnout of standard practice. Even as a trained physician, I knew I was not an expert in behavioral health or pharmacy. I knew I needed a team to deliver better care.

Practicing in a medical home

I joined the Neurobehavior HOME Program instead, and my sanity is glad that I did. It is a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) that cares for individuals with developmental disabilities. The patients have challenging behavioral and medical problems, but I have the support to provide quality care to my patients. I lead the Primary Care Team, but we also have a Psychiatry Team, Therapy Team, Behavioral Team, and Case Management Team. This is how medicine should be.

My fears of practicing medicine are resolved in this setting. Case managers coordinate care within and without the clinic walls. I get to enjoy the personalized and continuous relationships that family medicine provides. Specified times (we call it “predictable access”) to coordinate with other clinical team members is scheduled every day. I care for an underserved population, which adds its own reward.

Why health care is wicked hard

But this setting is not standard care. Health care is what’s known as a “wicked problem.” John Camillus, the Beall Professor of Strategic Management at the University of Pittsburgh, relates it this way:

“A wicked problem has innumerable causes, is tough to describe, and doesn’t have a right answer. Environmental degradation, terrorism, and poverty—these are classic examples of wicked problems. They’re the opposite of hard but ordinary problems, which people can solve in a finite time period by applying standard techniques.”

Sound familiar?

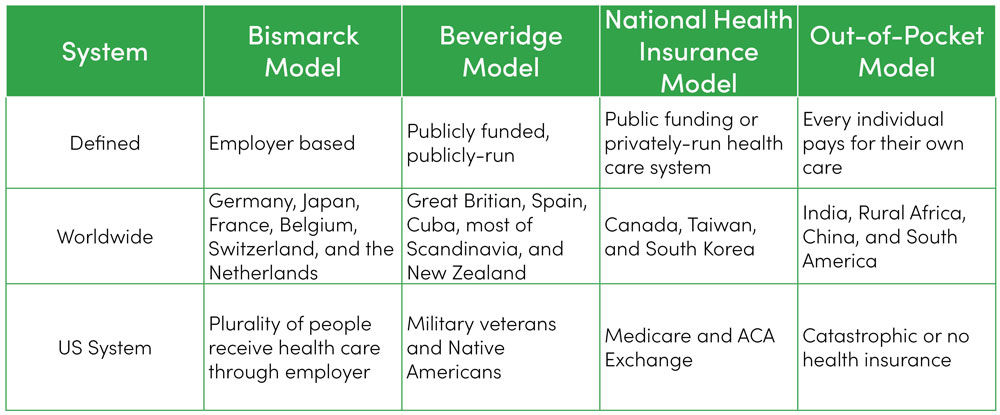

American health care is so “wicked” because it combines elements from at least four different systems.

These multiple payment systems have created a convoluted mess that informs delivery of care and its quality.

We’ve simply made our “system” too complicated to fix in any straight-forward, meaningful way. This is the “wicked” aspect of the wicked problem. Lauded economist Milton Friedman stated that any one of the above systems would better achieve the (then) triple aim of health care—even the British Beveridge Model—than our current piecemeal system.

Back to John Camillus’ explanation: Traditional organizational and management approaches aren’t up to the task of wicked problems.

“[Companies] can’t develop models of the increasingly complex environment in which they operate. As a result, contemporary strategic-planning processes don’t help enterprises cope with the big problems they face. Several CEOs admit that they are confronted with issues that cannot be resolved merely by gathering additional data, defining issues more clearly, or breaking them down into small problems.”

Sounds a little like VUCA–an acronym for volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous and coined by the military to describe the challenges of modern warfare.

The solution is teamwork

While we’re not able to redesign the entire American health care system, we can organize our care differently. The biggest underlying factor that contributes to improving our “wicked” problems within health care? Proper teamwork. It may seem too simplistic. But effective collaboration among multiple disciplines, within clinical settings, and even across organizations, have produced the best results to our problems within health care—burnout included.

As Ezekiel Emanuel, Chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, has pointed out, the best way to solve our health care problems is to change the way we deliver care.

Over the next number of months in this space, I will highlight practical elements that can lead to greater satisfaction and love of what we do as health care providers, both from my experiences and from others. We and our patients deserve better.

Kyle Bradford Jones

To disagree means failing to agree. Synonyms include to contradict, challenge or debate. Synonyms do not also have to include to argue, quarrel, dispute, bicker or clash. Pediatric intensivist Jared Henricksen shares the best path forward when words become clouded with emotion.

Listening to—and learning from—employees makes for a more humble and thoughtful leader. Chris Shirley, support services director, shares how he turned some stinging feedback into an opportunity to create community and inclusion.

Learning to listen is not only a leadership skill—it’s a life skill. Leadership training specialist Jess Burgett shares three practical tips for harnessing the power of listening with intent.