July 1, 2021 Update

Last year, as part of its ongoing response to the COVID-19 pandemic, University of Utah Health suspended the use of palm scanners at all check-in desks throughout the system. U of U Health has decided to permanently suspend the use of palm scanners.

U of U Health has created this list of frequently asked questions to help staff provide information to patients in case they are asked about what happened to the scanners.

Working through problems as a team

January 2017, palm scanners were installed in University Hospital’s Clinic 3 (Gastroenterology and Pulmonology). Doug Ostler had started as clinic manager just eight weeks earlier, but he embraced the unlikely opportunity—a change he was instructed to lead—and built a relationship with his team by focusing on shared vision and collaborative decision-making.

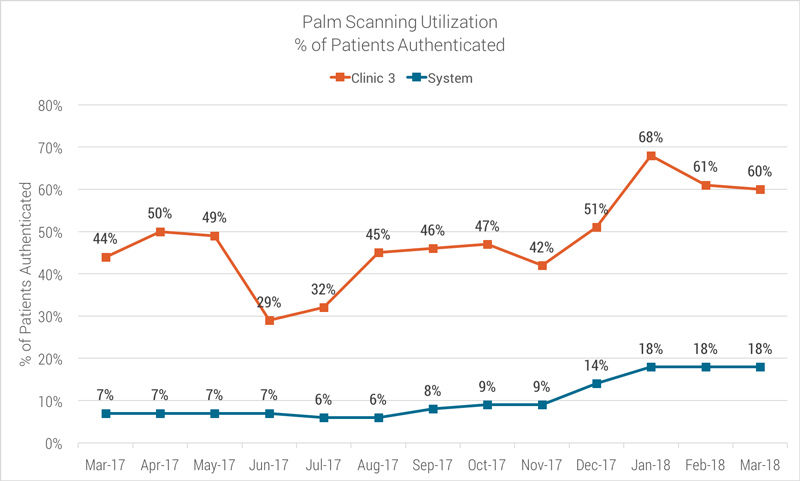

Doug worked with new patient coordinator McKenna Wilcox and outpatient service specialists (OSS) Lindsay Haas and Christina Woolsey to design and manage a workflow for the new palm scanning devices. By testing ideas together, the team transformed a big challenge into a patient-friendly process. Clinic 3 achieved palm scanning authentication rates above 60%—three times the system average.

Below, McKenna Wilcox, Christina Woolsey, and Lindsay Haas explain how they did it:

#1 Introduce palm scanning to patients

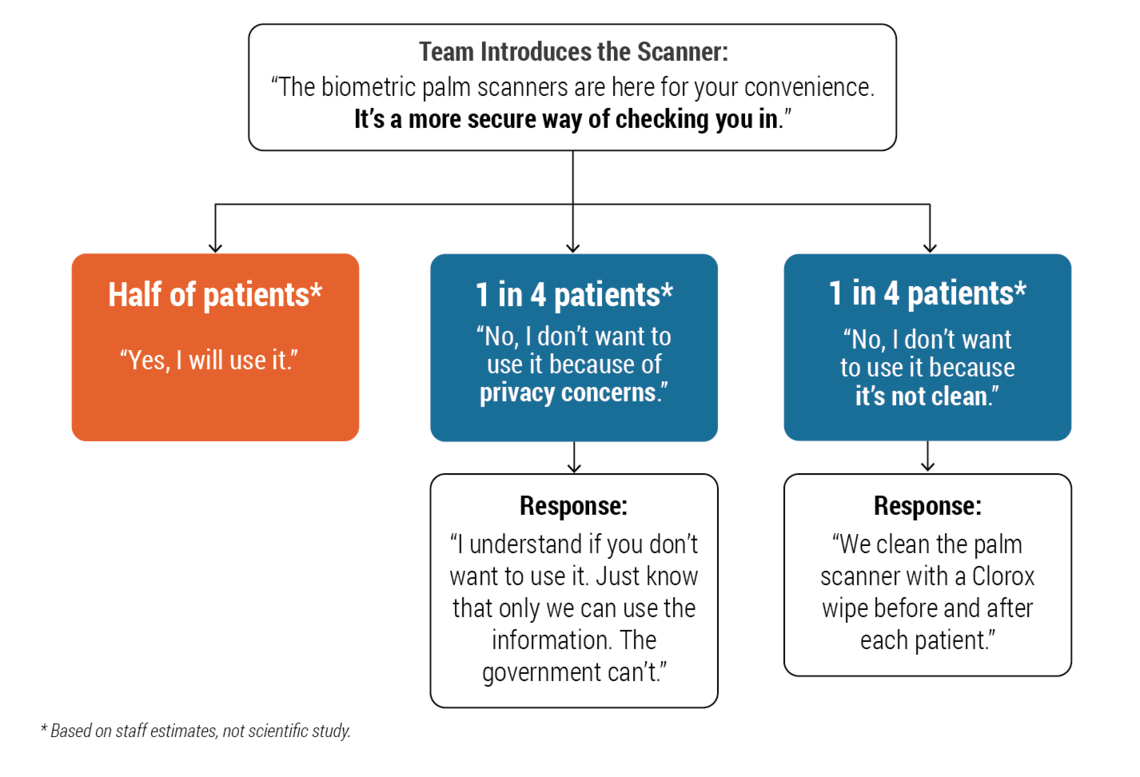

Once we understood the reasoning behind the palm scannersPalm scanning identifies patients with a high level of accuracy and security, offering an intuitive, non-intrusive, easy-to-use interface that allows health care professionals to deliver the right care to the right patient each and every time., we had to find the right verbiage to inform patients so we could help them feel more comfortable. We expanded on the scripting that our revenue cycle coordinator, Dawn Spor, provided us with—and presented it more simply to the patient so they understood that being safe is different than feeling safe. The right thing to say is what feels authentic to you.

McKenna’s introduction: “This is for you. The palm scanners are here for your convenience—it’s quicker and more efficient.”

Lindsay’s introduction: “A biometric palm scanner scans the veins in your palm. It’s a more secure way of checking you in.”

Christina’s introduction: “This is another way to identify who you are. Banks do fingerprints, we do your palm. After you enroll, next time you come in, you don’t have to pull out your ID.”

#2 Clean the palm scanner as the patient walks up

Half of the patients who decline to use the palm scanners do so because they’re concerned about cleanliness. Since Clinic 3 is a chronic disease clinic, we were instructed to Clorox the palm scanner after each use. We’ve made a point to do that as the next patient is walking up so that they see us cleaning it. We hear from patients, “Oh, I’m so glad you clean the palm scanners! I didn’t know you cleaned those!” It makes a difference.

#3 Tell patients how we keep them safe to build trust

As an OSS, we don’t want to frustrate patients. If a patient’s feeling uncomfortable, it makes your position a little uncomfortable—they’re unhappy and you’re left trying to comfort this unhappy patient. We were worried initially that patients would be frustrated by the extra step and the extra time. But that’s not a reason to not ask patients to set up palm scanning. In reality, it’s faster—and we tell patients that.

On the other hand, if we told patients we could check them in without palm scanning, they’d wonder why we have these machines in the first place. Then, they’d wonder if they really need to do all the things we ask them to. Unifying our message about palm scanning is about building trust in our system—we’re all looking out for you.

Patients seeing other patients use the palm scanners makes a difference, too. Most patients in Clinic 3 do a three-month return visit. For several months, we were registering first-time patients, but once we got past that stage and started finally getting returns, other patients would watch them go through check-in so much faster. It helped encourage others who might have been a little hesitant to start using it.

#4 Understand how the equipment works

We took time to understand how the equipment works so we could explain it to patients. When we realized that we were literally just scanning the veins in their palms, not taking their handprint, we could tell patients that and alleviate some of their fears.

Roughly half of the patients who decline to use the palm scanners do so because they’re concerned about privacy. They think the government might somehow use the information we gather. But we tell them, “It’s not a fingerprint—it’s not even a handprint. All it scans is the veins in your palm. We can’t use that for anything, just like we can’t use your handprint or your fingerprint.”

Doug Ostler's leadership principles that work

1. Improving together by sharing the why

My staff is my “why,” so when palm scanners were introduced, I wanted to give them the right tools to succeed. That meant understanding the why and the how of palm scanning so I could share that vision with the team. Our revenue cycle coordinator, Dawn Spor, did a great job training with the front desk. We focused on the benefit for the patient: this form of identification is more reliable. We’re less likely to make a mistake. After I provided that information, I let my team run with it.

2. Involve the team in managing new work

I talked with my team about why we were investing in this device and how to have the conversation with patients. It was important for me to communicate why they had to change their workflow. But by enlisting them to design and manage that workflow, they owned it. McKenna trained Lindsay, who in turn trained Christina. They all support each other.

3. Listen to feedback and brainstorm solutions together

Like any change, using the palm scanners was different than we initially thought. We discovered a few more steps: because it’s two-factor authentication, a patient still needs to provide their name before we can scan their palm. When my team asked if that process could work differently, I went back to Dawn Spor. We couldn’t change the process, but it was important to have the conversation. I wanted my team to see that I was following up on their questions.

Doug Ostler

Lindsey Haas

Christina Woolsey

McKenna Logan

Beliefs are the emotional foundation for excellence and can shape organizational realities. Positive beliefs build energy, enthusiasm, caring and creativity and can increase resilience and influence bottom line results.* Rob Kistler leads nearly 1000 people as the senior director of University Hospital’s support services (nutrition care, environmental services, customer service, safety, and emergency management). Here’s what he believes about his team.

What does it mean to take a system approach to problems? The discipline to learn as a team, patience to wade through hundreds of cases, and a diversity of perspectives. Utah’s Critical Care Senior Nursing Director Colleen Connelly, System Quality, Patient Safety, and Value Senior Director Sandi Gulbransen, and Associate Chief Medical Quality Officer Kencee Graves reflect on what they’ve learned by studying system problems with an interdisciplinary team.

Changing practice is personal. It doesn’t happen through edict or mandate. Changing practice requires ongoing respectful dialogue. It requires clear vision, data-driven analysis and the support of a dedicated team. Changing practice takes longer that you think it will. In this example, we recognize the power of a partnership in this challenging and important work.