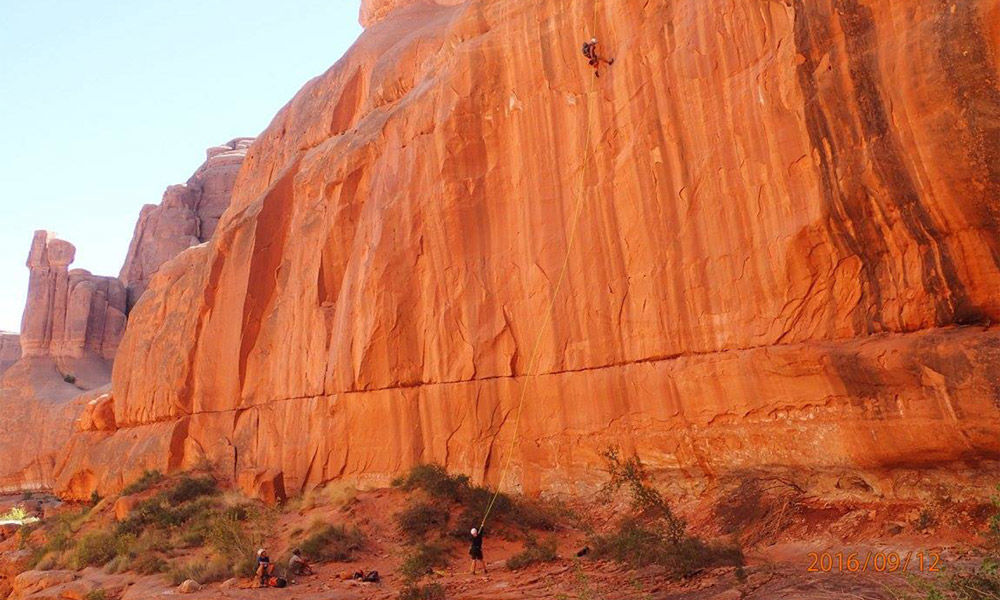

went canyoneering a couple of weekends ago. Canyoneering involves 3 to 12 crazy people deciding to wear 40-pound packs, enter a canyon, and do dangerous things in remote locations. General information about the canyon is known–length of rappels, distance, and time required in normal conditions.

But the canyon changes every day. So we work as a team to problem solve and “arrive alive” back at camp. There are redundancy plans to prevent injury, and we have a safety plan:

- If anyone in your party is injured, get help.

- Stay together.

- If you need help, whistle once. Or is it twice? Not sure, depends on the group.

I’m guessing you are starting to see the problem. This plan is not a high-reliability plan! There are three well-understood steps between us and harm. There are a lot of “what ifs” once you enter the canyon.

What happened on my most recent trip has me thinking about our safety plan. It was near the last hour of a 10-hour day. We were tired. One of our members became separated from the group. We violated rule #2: stay together. He went up when we went down. Sometimes this works in a canyon. That day, it didn’t.

As the three of us are waiting at the exit of the canyon, twilight set in. Temperatures started to drop. We yelled, whistled, and travelled back into the canyon. No sign of him. Then, we started to consider the possibilities: He’s lost, He’s injured, he had a medical issue. Would he be able to return safely?

During our 15-minute walk back to camp, we discussed what to do next. I realized we were past the planning stage and in the middle of a safety event. We called search and rescue. Four hours later our lost companion wandered back to camp. It was human error–overconfidence in his ability to find his own way back–that led him astray. Search and rescue were called off. A happy ending to a stressful day.

"I wondered how could we have prevented this near-miss in the future? How do you plan for the what-ifs?"

I started to think about the operating room and surgical “time outs.” Surgical “time out” is part of the Universal Protocol to verify the right patient, right procedure, and right surgical site prior to starting a procedure. If we, as a team, would have taken 10 minutes to talk about what we were going to do for the next 10 hours–taken a safety time-out to verify the plan–maybe we could have prevented the indecision that followed.

We needed to discuss today’s conditions, but we also needed to consider the what-ifs. What kind of decisions may confront us? What are the ways in which things could go wrong? How could our equipment fail? What about our communication methods? Engineering processes are usually built with these questions in mind. Are critical processes in your area three steps from harm?

Cindy Spangler

Using improvement methodology to solve one piece of America’s opioid epidemic. Dr. Sean Stokes and team used the practice of scoping to focus on one population and one procedure to achieve manageable, measurable improvement.

Safety as a value requires a cultural shift, not just getting people to talk about patient safety but to know how it impacts everything we do. U of U Health’s Director of Patient Safety Iona Thraen draws from the personal to highlight a system-based approach for moving from reactive to proactive patient safety.

For National Injury Prevention Day, Spencer Steinbach, Senior Nursing Director, discusses safety and injury prevention in nursing and the outdoors and shares tips for your next adventure.