ocial drivers of health (SDoH) are nonmedical factors that influence a person’s health. Safe lodging, education, air and water quality, regular employment, reliable transportation, and access to healthy food all play a significant role in health. In fact, researchers estimate that these factors impact 70%-90% of a person’s health, well-being and quality of life. By contrast, the services we offer in our clinics and hospitals only drive about 10-30% of our community’s health outcomes.

I (RyLee) wanted to bring this innovative lens of looking at a person's social needs from the research world into the clinical setting to impact the lives of people seen right now in our health care system. University of Utah College of Nursing professors Andrea Wallace and Brenda Luther had been developing novel solutions to screen for patients’ SDoH during common health interactions, like asthma care and visiting the Emergency Department. As a health care system, we knew we wanted to bring that work to more patients. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid had also announced that they would begin requiring health systems to screen for SDoH.

To meet CMS regulations, as well as additional guidelines around maternal mental health, we identified Womens’ Health as a great place to start. We partnered with Sarah Lauer from the Quality team and Brenda Gulliver, who leads nursing in Ambulatory Womens’ Health.

Our front-line team was also interested to more formally explore SDoH. Every day, we see how social drivers impact a person’s prenatal care. If a person is relying on bus service to get their appointment, they can sometimes arrive late or miss an appointment. We know that when we can address social needs when someone is pregnant, the outcomes improve – fewer babies are born underweight, which means they start out life healthier. Our question became – how can we help our patients get the care they need, even if it’s outside the resources we normally provide?

At the outset, one of our guiding principles was that addressing patients' social needs could not mean that our clinical staff would navigate social services on behalf of patients. We knew we wanted everyone – clinicians, nurses, MAs, etc. - to be able to practice at the top of their license. That meant that our clinic staff shouldn’t have to take time to figure out bus tokens, or other resources. Health care can’t solve everything, so we knew we needed to partner with outside expert social services organizations.

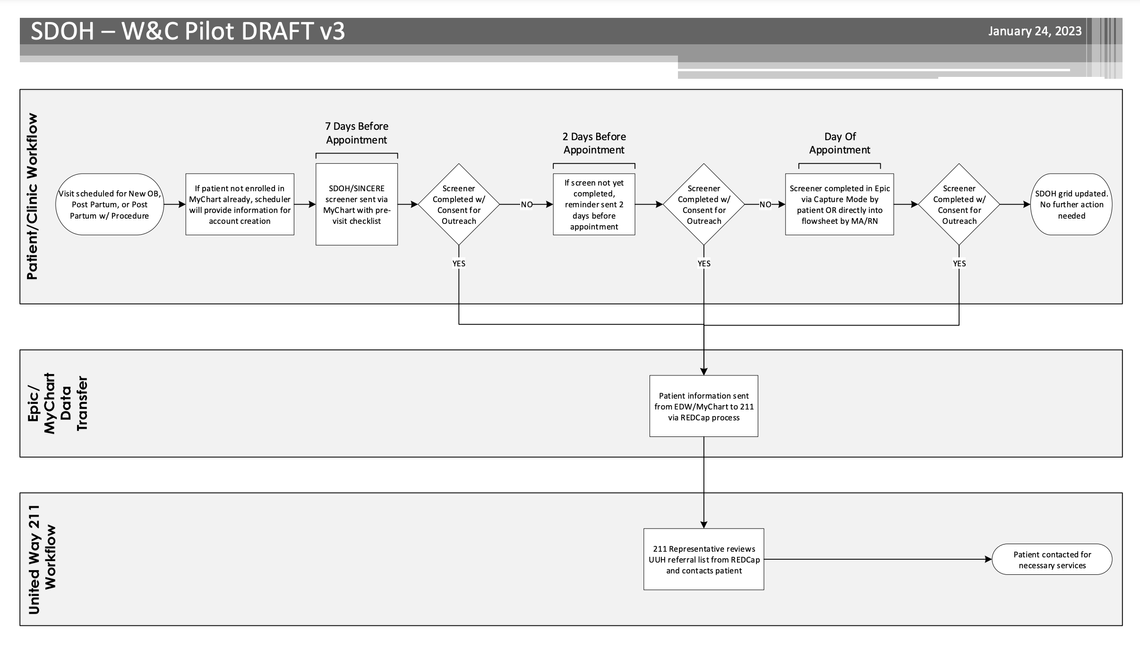

Our pilot project aimed to establish standardized SDoH screening questions into preexisting patient screening forms and connect at-risk individuals with assistance outside of the clinic, leveraging United Way 211.

The Project

Baseline Analysis

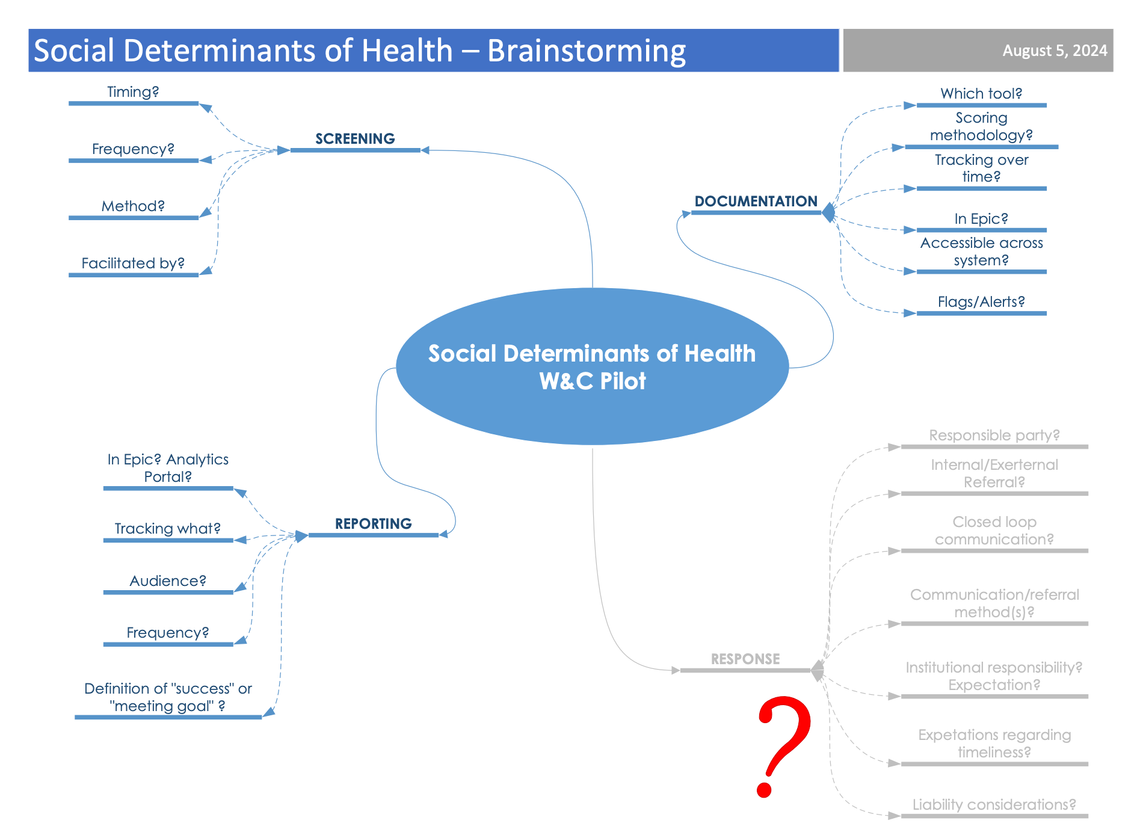

I (RyLee) started with baseline analysis a few years ago as a passion project. When Sarah and Brenda joined the project, Sarah completed the baseline analysis. We wanted to get a picture of the current landscape. First, we looked at all the SDoH questionnaires. There were three different SDoH screening tools in use across our outpatient clinics, and they all contained different questions. We also found that there wasn’t a lot of standardization across the system – some people were followed up with after screening positive for SDoH needs, some weren’t. After our baseline analysis revealed that there wasn’t a standard follow-up practice for patients who screened positive,

Forming the team

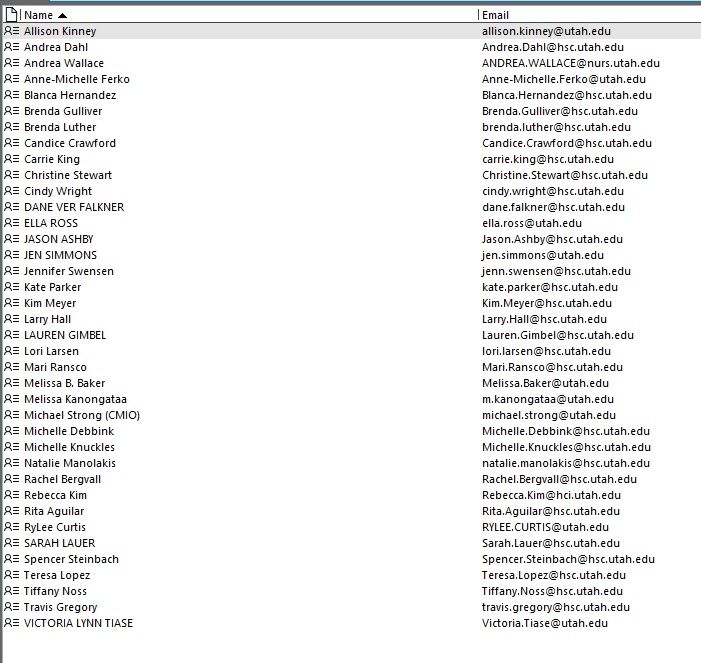

We assembled a diverse team. We brought in IT experts, informaticists, MyChart experts, and frontline staff to provide feedback on the intended workflow. While we met regularly as a large committee, we also broke into three subgroups that focused independently on workflow, standardizing questions and selecting a screening tool. We also included our College of Nursing colleagues, who were able to share their expertise from what had worked previously.

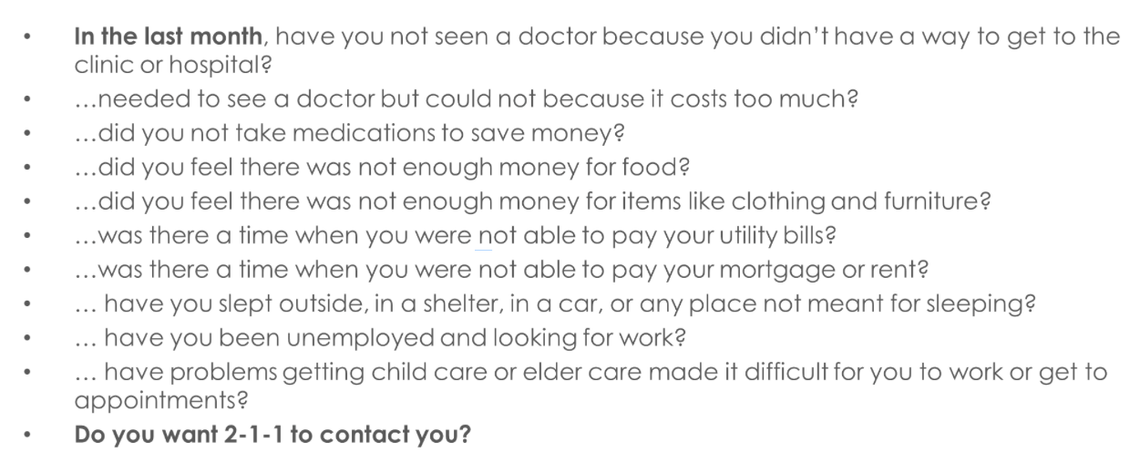

We knew we needed to design a workflow and tool to accommodate a population that doesn’t always ready access to computers, myChart, or the internet. We ended up picking the College of Nursing-designed tool, called the SINCERE screener. This screening tool is 10 questions, including a final consent question that allows patients to give us permission to follow up with them. Selecting this tool was a big step forward in standardizing the questions, not just for Ambulatory Womens’ Health, but for the entire system.

Another subgroup designed the workflow. We needed to be thoughtful in order to reduce burden on the staff and maintain an efficient flow, since the clinic is busy every day. At about the same time, our Womens’ Health Clinic was also implementing screening questions for maternal mental health. It meant that when a woman comes for a new OB appointment, she completes several screening questions, including the SDoH questions. In addition to new appointments, SDoH questions are asked at the 6-week post-partum check. If the patient uses myChart, they can complete the screener in myChart. They can also complete the questionnaire when they come into clinic and in private, if they choose.

Importantly, we established a process where if someone screens positive for SDoH needs, their information is automatically routed to United Way 211. We felt this was important – that United Way proactively reaches out to the patient, instead of us providing contact information to the patient. It takes the onus off the patient and puts it appropriately on the system to reach out.

Engaging the team

Our nurse educator, Melissa Baker, was a part of the process from the beginning. She was critical to support our staff in learning the new workflow. We have 11 sites, so our education plan required a mix of approaches. There were some in-person components, but we also had virtual staff meetings and newsletters. We also spent time educating our nurse managers. United 211 was part of our training as well. They provided scenarios that staff could expect.

Our teams were quick to recognize the value of the project. Many of them had spent years seeing patients suffer without having the tools to give them additional support outside of clinic.

Launching the pilot with storytelling for success

Our group’s persistent efforts, combined with the infrastructure established by the College of Nursing, gave us the momentum we needed to launch the pilot in April of 2023.

In the last year alone, our pilot has made a difference in many patients’ lives. Sharing the stories of results directly with our teams has been a big part of our success. Andrea and the College of Nursing team had already included stories in their research grant, and she shared how hearing the positive impact for patients motivated ongoing effort.

Here are some short stories we received and shared with our team:

- One patient, seeking financial assistance to cover their child’s medical bill, received help scheduling an appointment with Medicaid.

- A single mother, recently homeless and unemployed, needed financial assistance to cover her portion of utilities at her friend’s house. The service navigator successfully helped her not only get utility assistance, but also clothing for her and her child, diapers and baby formula.

Lessons learned and next steps

We started with human connection. We knew that the feeling we wanted to create was personal attention - a person calling the patient to follow up on their needs. We didn’t start with a technology and back into the feeling we wanted to create. The technology supported the human connection. That’s the question for health systems – where do we invest our energy when it comes to social drivers of health?

It felt empowering to not only screen patients for social needs, but also to be able to connect them to help. We worked backward from the 211 process because we knew that just screening patients wasn’t enough. And knowing that the system would work for these patients made the process improvement work feel effortless with the team and staff. The staff cares so much about the patients, and this process helped them actually help patients with things that had felt previously out of their control. It was so heartwarming to see.

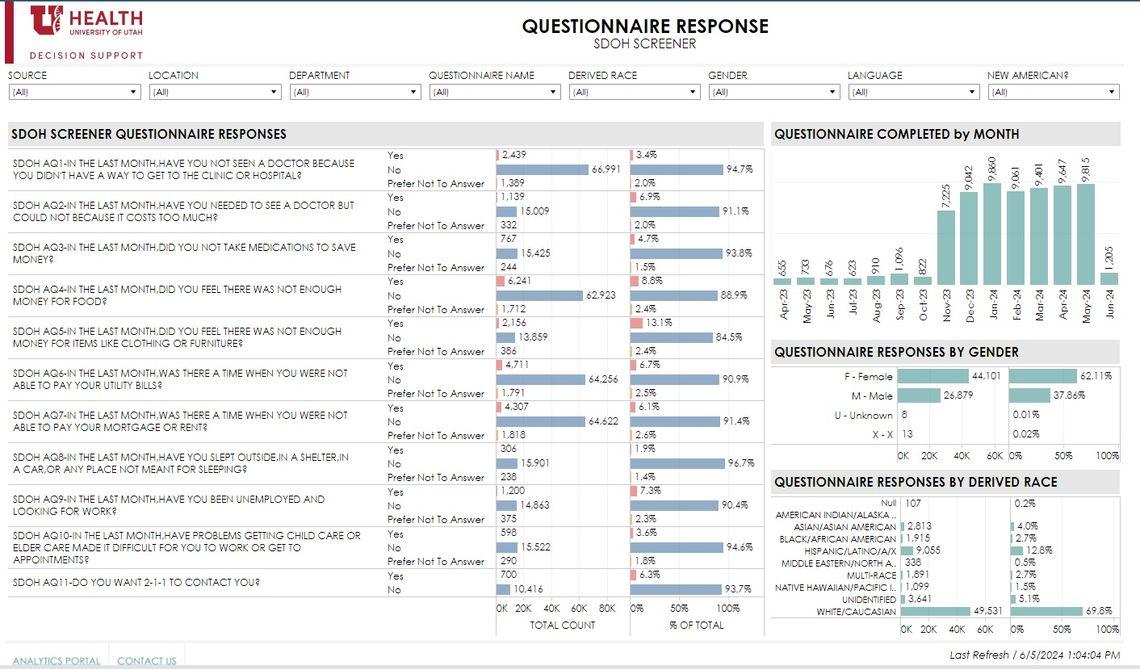

The SDoH pilot has also helped us identify and address some of the biggest needs in our patient base. We can now say factually, food security is one of our highest patient needs. It makes sense for the health system to support the Utah Food Bank. We’ve also supported the food bank at Stansbury Elementary, and we can see that investing our funds as a health care system tie back to the patient’s social needs that impact their health.

We also saw that roughly 13% of patients don’t have enough money for furniture and clothing. That’s an interesting finding when you think about that these are patients who are adding new members of their family, and they may not have the resources for cribs and clothing. It helps us understand what is facing these families and how we can connect them to help.

Initiatives like this prompt us to advocate for more support outside our clinic walls and think about how this workflow to connect to 211 would function in the inpatient setting. Right now, we provide 211’s information to patients, but we want to investigate proactively routing to 211 instead of putting the burden on the patient to reach out.

From the beginning, our staff knew that, when they identified an issue for the patient, they would have the power to help them in a meaningful way. That sense of empowerment and engagement has carried us over the past year. We are so grateful to everyone who has contributed along the way.

RyLee Curtis

Brenda Gulliver

Chantal and Chanda discuss challenges New Americans face based on experiences with the Redwood Health Center, and how their teams are committed to improving support for patients facing health disparities.

Huntsman radiation oncologist and population health scientist Gita Suneja, and maternal-fetal medicine specialist and racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities researcher Micelle Debbink, share five practical steps health sciences educators, researchers, and clinicians can take toward delivering more equitable care today.

Physician colleagues provide a basic understanding of the impact of using race and ethnicity in academic medical education, research, and healthcare delivery to develop shared language and understanding.