“Wrong that every child does not have precisely the same chances. It takes so little, and costs so little in comparison with the interest neglect collects over the years. The opportunities should be taken for granted; they should be offered eagerly instead of having to be fought for.”

– Thelma Purtell

he root causes of health disparities and the lack of workforce diversity are complex. A multifaceted approach is necessary to address them. As pediatricians and former teachers, the achievement gap is at the forefront of our minds. The achievement gap refers to the disparity in academic performance among different demographic groups. It underlies the inequality in health and career opportunities.

As a health care community, we must work together to close this gap. Recent dialogues on the importance of community engagement to achieve health equity and workforce diversity have been incredibly inspiring. By extending partnerships to schools and local communities, we can help to create and promote equal, if not more equitable, educational, health, and future career opportunities for all children.

What is the achievement gap?

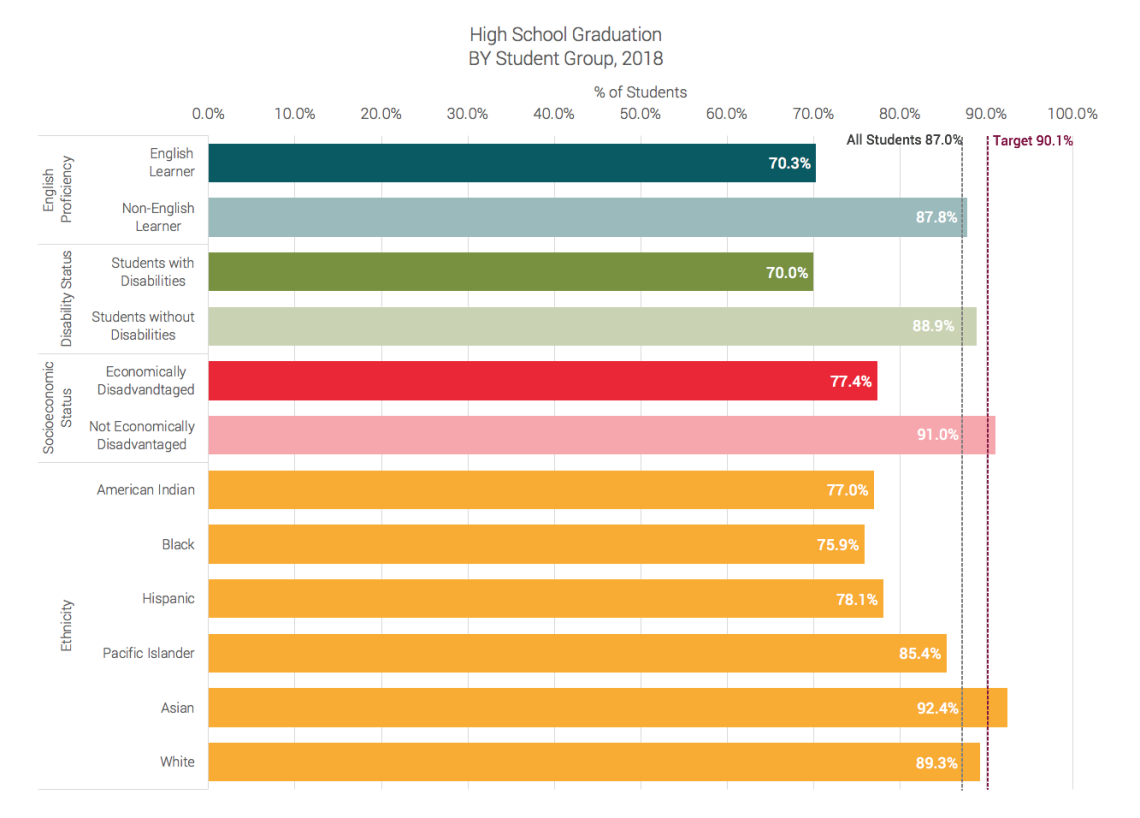

Despite reductions in the achievement gap over the last decade, a significant gap persists between children living in urban and rural areas, children born into wealthy and poor families, and children of different races/ethnicities.

Nationally, about 50% of Black, Hispanic, and Native American students graduate from high school compared with 75% of non-Hispanic whites.1 Lower-income children are less likely to graduate from high school than their higher-income peers.2 In Utah, the statistics are similar.

The gap in academic achievement is driven by the opportunity gap that starts before a child even enters school.3 Children living in poverty as young as 3-years-old lag behind affluent children in cognitive language and socioemotional skills.1 This opportunity gap persists and can widen throughout K-12 schooling.3

How does the achievement gap affect health disparities and workforce diversity?

Education is a key social determinant of health. Duration of education is a better predictor of health and longevity than either cigarette smoking or obesity.4 At the same time, good health positively affects school performance. This reciprocal relationship between education and health creates a negative feedback loop where disparity in one exacerbates disparity in the other.

The achievement gap also affects workforce diversity, particularly in the health sector. Currently, only 9% of physicians identify as Black, Native American or Alaska Native, or Hispanic or Latino. The percentage of Black males matriculating into medical school is actually declining.5,6 As the diversity of Utah’s population will grow over the coming decades, the higher education achievement gap is, unfortunately, predicted to widen.7 The unequal opportunities that children of color, potentially even more for Black boys, to academically achieve are impacting future career trajectories.6

Given the importance of educational attainment to reduce health disparities and diversify the workforce, and given that improvements in one can positively affect the others, efforts should be made to close the achievement gap.8

How can the health care community help to close this gap?

We can help to close the achievement gap through advocacy, counseling families, and partnering with schools and community organizations.

Improve access to high-quality daycare and early childhood education programs

School readiness and achievement starts with access to high-quality daycare from infancy. Unfortunately, many families have financial barriers or live in daycare deserts. Early childhood education programs, most notably Early Head Start, significantly improve children’s socioemotional, language, and cognitive development, as well as their readiness for kindergarten.9 The positive downstream effects of early childhood education are numerous, including a higher likelihood to graduate high school, attend colleges, and receive a post-secondary education, and a lower likelihood to be unemployed and unhealthy.10, 11 Health care providers should help families access high-quality daycare and Head Start. We should advocate for expanded access to these programs through funding, such as expanded Child Care Development Block grants or Head Start funding. We should also educate policymakers about the importance of high-quality childcare and early education.

Promote school readiness at home

During well-child visits, health care providers should prioritize school readiness by maintaining Reach Out and Read, a program that integrates reading into pediatric practices, coaching parents about reading, modeling reading, and providing books to children. Reach Out and Read increases attitudes and frequency of parental reading to children and those children demonstrate higher language scores.12-17 Research supports a dose-dependent relationship; the more Reach Out and Read, the higher the score.16 We should also help families to access community resources such as library cards and school readiness programming.

Partner with pipeline programs

Well-designed pipeline programs are successful in raising the academic achievement of their participants.18 Partnering with pipeline programs can promote the participation of minority, low-income, or rural students in STEM. There are many established programs locally. An example is Little RUUTES (Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience), a program through the University of Utah School of Medicine that engages K-12 students from rural and underserved areas and introduces them to a variety of health sciences programs and activities.

Support local educational systems and school-based health services

Healthier students are better learners; therefore, health care providers should actively partner with local schools and support school-based health services. School-based health clinics can significantly improve student attendance and grades.19 We should also prepare trainee health providers to counsel families on school-related topics and how to interact with school systems.

Increase funding for mental health services

Similar to physical health, emotional wellbeing is positively associated with improved school performance. While there is a mental health crisis affecting adolescents from all backgrounds, Black children are disproportionately impacted. The suicide rate among Black youth has been increasing faster than any other racial/ethnic group.20 Lack of adequate mental health services in schools can lead to treatment of behavioral problems as conduct problems, resulting in suspensions and altering achievement trajectories. We must advocate for improved school-based mental health services.

Advocate for afterschool programs

In addition to in-classroom activities, afterschool programs can curate a positive self identity through promotion of mastery, community, autonomy, and even generosity. Adults serving in roles other than teachers, like coaches or club advisors, can provide strong mentorship. These programs can enrich the learning environment by fostering a commitment to school attendance and academic engagement. We should support and advocate for high-quality afterschool programs and ensure accessibility to all students.

Rebecca Purtell, MD, MSCI, a Pediatric Hospitalist, was previously a high school math teacher in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Cheryl Yang, MD, a Pediatric Emergency Medicine fellow, was previously a middle school science teacher in the Bronx, New York.

- Fiscella, K., & Kitzman, H. (2009). Disparities in Academic Achievement and Health: The Intersection of Child Education and Health Policy. Pediatrics, 123(3), 1073-1080. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0533

- Utah State Board of Education. (2019). Utah Achievement Gaps. Retrieved from https://www.schools.utah.gov/file/9489b372-76d2-4f04-bc5e-c6a7eab9ef9e

- Peterson, J. W., Loeb, S., & Chamberlain, L. J. (2018). The Intersection of Health and Education to Address School Readiness of All Children. Pediatrics, 142(5), e20181126. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1542/peds.2018-1126

- Johnston RB. (2019). Poor Education Predicts Poor Health - a Challenge Unmet by American Medicine. NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201904a

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2020). Creating and Sustaining a Diverse and Culturally Responsive Workforce. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/diversity-issues

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2015). Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine. Retrieved from https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/84/

- Curtin, JA. (2019) Utah’s Growing Opportunity Gap: The Impact of Shifting Demographics on Utah’s Postsecondary Educational Attainment. Utah Systems of Higher Education Issues Brief. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED601919.pdf

- Komaromy, M., Grumbach, K., Drake, M., Vranizan, K., Lurie, N., Keane, D., & Bindman, A. B. (1996). The Role of Black and Hispanic Physicians in Providing Health care for Underserved Populations. The New England journal of medicine, 334(20), 1305–1310. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199605163342006

- Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C. M., Schochet, P. Z., Brooks-Gunn, J., Paulsell, D., Boller, K., Constantine, J., Vogel, C., Sidle Fuligni, A., Brady-Smith, C. (2002). Making a Difference in the Lives of Infants and Toddlers and Their Families: The Impacts of Early Head Start. Volumes I: Final Technical Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/making-difference-lives-infants-and-toddlers-and-their-families-impacts-early-head-2

- Bauer, L. and D. W. Schanzenbach. (2016). The Long-Term Impact of the Head Start Program. The Hamilton Project, the Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/long_term_impact_of_head_start_program.pdf

- Deming, D. (2009). Early Childhood Intervention and Life-Cycle Skill Development: Evidence from Head Start. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 111-134. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/app.1.3.111

- Mendelsohn et al. (2001). The Impact of a Clinic-Based Literacy Intervention on Language Development in Inner-City Preschool Children. Pediatrics, 107(1):130-4.

- High et al. (2000). Literacy Promotion in Primary Care Pediatrics: Can We Make a Difference? Pediatrics, 105(4 Pt 2):927-34.

- Sharif, I., Rieber, S., & Ozuah, P. O. (2002). Exposure to Reach Out and Read and vocabulary outcomes in inner city preschoolers. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(3), 171–177.

- Needlman, R., Fried, L. E., Morley, D. S., Taylor, S., & Zuckerman, B. (1991). Clinic-based intervention to promote literacy. A pilot study. American journal of diseases of children (1960), 145(8), 881–884. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160080059021

- Weitzman, C. C., Roy, L., Walls, T., & Tomlin, R. (2004). More evidence for reach out and read: a home-based study. Pediatrics, 113(5), 1248–1253. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1248

- Theriot, J. A., Franco, S. M., Sisson, B. A., Metcalf, S. C., Kennedy, M. A., & Bada, H. S. (2003). The impact of early literacy guidance on language skills of 3-year-olds. Clinical pediatrics, 42(2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/000992280304200211

- Gándara, P. (2006). Strengthening the Academic Pipeline Leading to Careers in Math, Science, and Technology for Latino Students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5(3), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192706288820

- Public Impact and Oak Foundation. (2018). Closing Achievement Gaps in Diverse and Low-Poverty Schools: An Action Guide for District Leaders. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED589275.pdf

- Watson Coleman B. (2019). Ring the Alarm: The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Black Caucus Emergency Task Force on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health. Retrieved from https://watsoncoleman.house.gov/uploadedfiles/full_taskforce_report.pdf

Rebecca Purtell

Cheryl Yang

The crises of Covid-19 and police brutality have highlighted systemic racial inequity in the United States and the need to consciously dismantle the forces that cause racial health disparities. PA students Scarlett Reyes and Jocelyn Cortez brought together Black patients at the University of Utah to share their experiences. Their advice: build cultural competence and be mindful of microaggressions.

Transgender and gender diverse patients face systemic discrimination in our broader society and inequitable access to needed care. Ariel Malan, program coordinator and Andy Rivera, volunteer for Utah’s Transgender Health Program, share how to create an inclusive care environment for this vulnerable population focused on trust and respect.

As Redwood Health Center’s program coordinator serving new Americans, Anna Gallegos has learned valuable lessons that can help all of us better care for patients of refugee background and vulnerable populations. Here are three suggestions to help make caring for patients easier.