MLK Week 2023:

This discussion with Reverend France A. Davis and the J. Willard Marriott Library was a part of the University of Utah's Equity, Diversity and Inclusion's MLK Week.

Transcript

Allyson Mower: It's so nice to see you all here. Thank you for attending this event, this MLK Week event. My name is Allyson Mower, I'm a librarian at Marriott Library. We would want to welcome you and thank you for attending today. We have a number of events going on on campus. Yesterday we had the rally and the march, it was really great, over at East High, walking up to Kingsbury Hall, it was wonderful. Today, we have this event with Reverend Davis. The Resistance Revival Chorus is here, they're performing tonight. There's a screening of Till tomorrow. The keynote is Wednesday, and then there's an MLK Jubilee on Friday up at the Black Cultural Center. So a week's worth of wonderful event. Again, so wonderful to see you all and welcome. We have a number of things going on with today's event. It's gonna be a conversation with Reverend Davis. We also have items from the collection, so we're really wanting to highlight what's in the collection at the library, so people kinda know how to use it and do research and create new works, create new books, movies, films, documentaries, whatever the work might be. So Reverend Davis, as you probably know, donated his papers recently just last October. Over 1100 sermons, over a thousand sermons, it's an amazing collection.

AM: So it's currently being processed and also being digitized, so we're hoping that can become a really core research resource for the community to tell the story of black people in Utah. We also started and launched the France Davis Utah Black Archive in October. It's a digital-based archive and it's community-based, crowd-sourced. So we want to really get your content. We're very interested in your content, so that we can build a great powerful collection, strong collection, and have great stories that are told from those collections. So those, that's what's on display over here, some books in the collection, and then material from Reverend Davis's papers and other items in special collections. So Rachel Ernst will be over there if you want to talk to her about the collection, and then Donna Baluchi from Eccles library will be over there and I will be over there as well. So on to today's event, we are streaming it live, so hello to those watching online. It's being streamed through Facebook, but really it's about all of you here in the room today. We're so grateful that you're here with us, and we want to take questions from you. This really is a conversation with Reverend Davis, but I am joined by Eddy Thomson. He works for L3 Communications, and he's also on the advisory board for the Human Rights Commission, the Utah Human Rights Commission.

AM: So this is a great partnership between the University of Utah and L3 Communications. Eddy is going to ask questions of Reverend Davis, we have them prepared, but of course, we want to hear from you, and Reverend Davis wants to hear from you and to be able to have this conversation about this year's theme of choosing love over hate. So that's kind of our format. And then because we are streaming, we're also recording. If you'll just be conscientious of the microphone so that we can capture your question if you do choose to ask one, we can capture it with Facebook and then on the recording as well. So we have Heidi Brett here and Jordan Hanson, who have some roving microphones, so just wait for them, and Eddie will help facilitate that question and answering period with Reverend Davis. So, on to our guest speaker, our keynote speaker, essentially our guest of honor. For today's event, we are very lucky to get to have a conversation about this year's theme, Choose Love Over Hate with Reverend France Davis. Reverend France Davis once marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. From Selma to Montgomery.

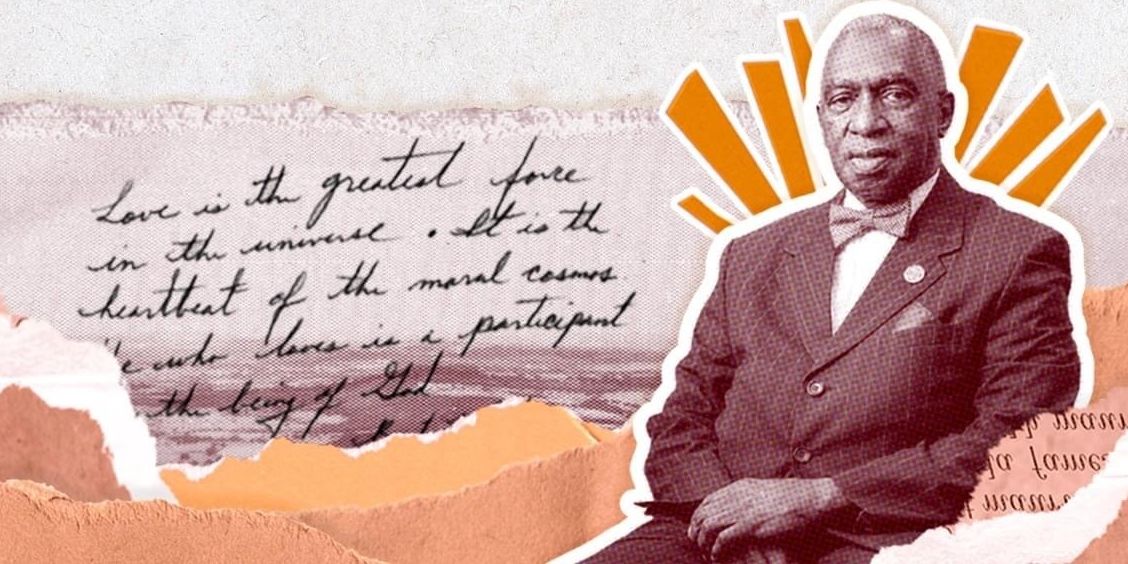

AM: Now retired, Reverend Davis served as a pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Salt Lake City for more than 45 years. He has been Pastor Emeritus since December of 2019. He came to Salt Lake City in 1972 as a teaching fellow and graduate student at the University of Utah. He was appointed instructor in communication and ethnic studies courses earning a Distinguished Teaching Award among other honors. He retired in 2014 from the U as an Adjunct Associate Professor Emeritus. He holds numerous honorary doctorate degrees, including one from the U of U. He has written four books about Utah's black history on display over here, including a memoir titled France Davis: An American Story Told, published by the U of U Press. Davis currently serves as the chapel into the U's football team. In October of 2022, the Marriott Library established the France Davis Utah Black Archive in order to capture and preserve the stories of black people in Utah. Eddy and Reverend Davis.

[applause]

Reverend Davis: Thank you. I wish my wife and children are here to learn who I am. [laughter] You listen at that introduction, and you have to have realized that you are somebody and that your family ought to know about who those people are. So I'll tell my wife when I get home. My son will be here later on. He works, he practices medicine at the Huntsman Neuropsychiatric hospital here on campus, and so he may be a little late in getting here, but he'll be... He's a friend of Eddy's. Good to see all of you. Glad all of you are here. I wanna make some opening remarks and then turn the time over to you and Eddy for whatever questions you'd like to ask. I was born and reared during the days of separate but equal. Those were times when the, legally the law said that African-Americans and Whites didn't need to go to the same schools or the same restaurants or the same hotels or other places, as long as those places were equal. Now, of course, they never quite made it to equality as far as I'm concerned.

RD: And so I grew up about 100 miles from where Martin Luther King Jr. Grew up, and where we... But we didn't know each other. I then went to New Jersey for the summer and worked for New Jersey in the summer, 1963, delivering furniture. And on my way back home, got to Washington DC, and there were all kinds of vehicles, outhouses, trucks, cars, buses and people, and I asked my sister what was going on and she said, "Don't you know that Dr. Martin Luther King and the marches on Washington are here, and tomorrow will be the day." So I hung around a while and didn't get to meet Dr. King, but was a part of the March on Washington. A year later, I was a student at Tuskegee, which is a little college in Alabama, started by Booker T. Washington, popularized by George Washington Carver. And as a student there, met all of the significant named African-Americans that were in the country. They came to Tuskegee for various reasons, including Martin Luther King Jr, who came. Martin came, and there was a march that the students at Tuskegee had helped to begin in Selma Alabama, and that march from Selma would go all the way to Montgomery Alabama.

RD: And I was one of those students, unnamed and unknown, but one of those students who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King from Selma to Montgomery. It was an exciting time. Dr. Martin Luther King was an exciting person. He could talk to anybody at any level, no matter whether they had a PhD as he did, or whether they had no D as my Dad did, and many other African-Americans had no D. They had no training, no formal education, but Martin Luther King could talk to them. And everything that Martin Luther King Jr. Did, I believe he did it for other people, not for himself. He didn't ride the bus for himself, because his dad had a brand new automobile. So he didn't need to ride the bus. He didn't stay in hotels because that's where he needed to stay, but he stayed in them because he was trying to bring about full acceptance of all people in the United States of America and in the world. And I remind you as you gather here today that Martin Luther King's work was not of just about work in the United States of America, but also about work abroad and other places. And the kind of segregation that existed in the south of the United States of America also existed here in Utah. In fact, if you were to go to the Century Theatre, you'll see a big picture hanging on the wall that says, "Colored entrance to the balcony."

RD: And when the most famous African-American musician came to Utah, she was allowed finally to stay at the Hotel Utah, which is now the Joseph Smith building. But she had to ride the service elevator and she had to eat her meals in the room. And although she was well known in other places and well-known as a singer and as a voice by the President of the United States of America, she still here in Utah was treated differently. So I grew up in that sort of setting. That was my beginning experiences. I'd be glad to share with you details about anything that you would be interested in knowing about. I wanted to thank the library for their collection of materials, and those of you who are African-American in particular, if you have materials, papers, the library would appreciate getting those and storing those in the library so that they would be available for research. By the way, my son France's gotten here. And France, would you just raise your hand.

[laughter]

RD: He's kind of shy, but that's France. So I turn you now over to Eddy to ask whatever questions you wanna ask, and let's have a conversation between me and you and others that are online as well. Eddy.

Eddy Thomson: Yes. So, thank you guys for being here today. We're so grateful for Pastor Emeritus France A. Davis to be here today to share with us his experiences in different things. Dr. King once said, "Everyone can be great 'cause anyone can serve." And I think when you look at the body of work that Pastor Emeritus France A. Davis has put together... I mean, he's got a street named after him. He must be doing something right. [laughter] So we're gonna kick it off. If you would just raise your hand if you have a question. I'm gonna kick up with the first question here.

Pastor Davis, what process does one take to make a choice such as choosing love over hate?

RD: Recently there were a number of us, including the Jewish community, who attended a conference eradicating hatred in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. When we attended that conference, we learned a lot about what already exists and how there are people that are still promoting hatred simply because they are different in one way or the other. Either they're different in terms of their skin color, different in terms of their education, different in terms of their political affiliation, different in terms of their economic development. And we learned about how that is existing all over the country, all over the world, really.

RD: But to have a conversation that suggests that love is a much more powerful tool, as Dr. Martin Luther King suggested it was, a much more powerful tool for us to use, is a great thing for all of us to commit to do. We are all in the boat together, and if my end of the boat is sinking, then eventually your end of the boat is gonna take on water and it's going to sink as well. And so we've gotta have this conversation between all of us. I go to the legislature regularly, and they always, they know me when I walk in the door and somebody is bound to identify me. There he is [chuckle] and they've then labeled me one way or the other.

But if you and I went together, if all of us joined our arms and our hands together and talked the same talk with the same conversation, we would likely get much more done.

Can you share a couple of experiences where you saw an example of choosing love over hate?

RD: I saw examples of choosing love over hate by Dr. King himself. When in Selma, Alabama there were those who would trample us with horses, authority figures. They would set dogs on us in Birmingham, Alabama, and use fire hoses. But Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Was the kind of person who believed that instead of fighting back, instead of giving even, instead of vengeance coming from the persons to whom it was demonstrated that we ought to demonstrate love. And so one example is how he dealt with the authority figures, the authority figures who were always trying to do harm to him. There's a famous photograph about Dr. King being arrested by the policeman. And his arm is bent behind his back. And the story is that he was arrested for driving the wrong speed in the area which he was driving on. Anybody want to guess at a 30 mile an hour speed limit what speed he was driving? Anybody want to guess?

RD: Less than 30. Less than 30. He was driving less than 30 miles an hour. And yet was arrested for driving too slow. Most of us, we are shaken by the red and blue lights that flash behind us when we are driving too fast, but seldom when we are driving too slow.

Angie: Thank you so much for coming to talk to us today, and for your service to Utah and the University of Utah. My name is Angie and I work kind of next door at a research center here on campus. I was attending the tanner Lecture with Heather McGee. And when you just talked about the boat sinking, her metaphor is draining the pool and how coming together in communities has been a very important way for us to move the conversation forward and continue to work together towards that which you also referenced.

Given your opportunities to live in many parts of the country, what do you see as particularly challenging or unique issues here in the state of Utah, in our community that we might need to be tuning into harder, more specifically for our culture, our community, and the history that comes with that?

RD: Thank you for asking that question. When I first came to Utah, I've had a very negative experience. I was denied housing. And I think it was because of my skin color. I'm not sure, nobody ever said, but I think it was because of my skin color. The landlord took one look at me and said, "Not here. You not gonna stay in this place." And I asked why. And he said that the tenant that had been there a year before me had returned and that he was going to rent the place to that tenant. Well, Dr. Boyer Jarvis, Dr. Dave J. Bush, who were both professors here on campus and I, took the landlord on and before we were done with the landlord, the landlord offered me anyone of his 100 apartments that he owned in the city. [laughter] And of course, I turned them all down and stayed in the international house, which is here on campus for the first year that I was here. But fair housing was a real problem back in those days. It's still in some real estate contracts still today. There are restrictive covenants which say whether you can buy a house east of Foothill Boulevard or not, because you are a member of "The servant class", the servant class. And that would be the people of Asian background, people of Native American background, people of African-American background, and people of Hispanic background.

RD: So, there's still those kind of restrictive covenants that we still need to get removed. Representative Sandra Hollands last year sponsored a resolution to get rid of slavery as a part of the Utah code. And, we still got a lot of work to do. We still have economics that we need to work on. There are not many people who have reached the level that Thompson has reached at L3 Communications, and yet L3 made more money in one year than any other company in the state of Utah. But there are not many people who have reached his level. There are not many people who have become presidents. There's only been one Black college president in the history of the state of Utah, and she was president of the college in Price, Utah, stayed a while, and then the board of trustees decided she had stayed too long, and educationally had to get rid of her. So, education, economics, politics, and then social activities are areas that we need to work on. We need to say to African-Americans, "You can go and participate in any social activity that is going on around the state of Utah, that you wanna go and can't afford to go to participate in." So, those are four of the things that I think we still need to work on.

ET: Thank you for that question. I'll stay in that playground a little bit for a second. You talked about systemic reforms and things of that nature, challenges that we still face.

Can you share a couple of the things that you've done throughout your career, helping shape a better Utah and better companies and systems and things of that nature?

RD: In 1983, Congress passed the law declaring that the third Monday in January was a legal public holiday, but Utah was one of the seven states that said, "The federal law does not apply to us." And so, we had to get a separate law, and I was the chair of the committee. We got a separate law, introduced in the state legislature. First year, it went down, resounding, it was defeated. The rest of the year, I spent time trying to educate legislators all across the state. And I traveled from Blanding to St. George to Salt Lake, to Logan, trying to educate the legislators that it was important that we have a Martin Luther King holiday. And finally, one of the legislators challenged me to a debate on Take Two. Take Two was a television show. Some of you... Anybody remember it?

RD: He challenged me to a debate. We debated the issue and at the end of the debate, he asked the moderator, What could he do to make sure that such a law as Martin Luther King's holiday be passed in the state of Utah? And then, he became the sponsor of the bill for the House of Representatives, in the state of Utah. He's still alive, he's still active. If I were to tell you his name, you'll hear his name regularly whenever there's a challenge to any activities that are done by the authorities of the state of Utah. So, that's one of the things that we've gotten done. We've gotten a Martin Luther King holiday. We got a street name for Martin Luther King, and on that street is Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church, which is the oldest Black organization in the state of Utah, and certainly the oldest church.

RD: In Calvary, Baptist would be the second oldest, but Trinity would be their oldest. Also, the Mignon Richmond Park is on that street. Mignon Richmond was the first African-American to graduate from college in the state of Utah from Logan, and never was able to get a job in the area in which she graduated. Not because she wasn't qualified, but because of her skin color and by the way, her niece just died two days ago. And we gonna have a funeral service for the niece of Mignon Richmond. So, I think some of the things that we have done, we had gotten done has been related to Martin Luther King, the street being named, the park being named Mignon Richmond, and many other things that we can think of.

ET: I wanna open it up to any other questions. Does anybody have any questions for Pastor Emeritus Davis? There we go.

Emma: Good morning, Reverend Davis.

RD: Good morning, Emma.

[laughter]

Emma: We have been participating in MLK activities throughout the week and these coming days as well. And as we were at the MLK march yesterday at East High School, one of the teenagers said to their parents, "Why we gotta keep telling people to love one another, shouldn't they just automatically do that?" So, Reverend Davis, from your experience and talking about love and building this community, this beloved community, why we gotta keep talking about this, Pastor?

[laughter]

RD: It's natural for us to hate one another. It's a natural sort of feeling to decide that what we hear about people that are different than us is worthy of hatred. So, it's natural to hate.

In order to counter hatred, we've gotta do everything within our power, by telling people, by showing people, by doing it ourselves to love one another regardless of our differences.

You are aware that my toilet flushes the same way as yours. [laughter] You do know that my stove turns on with the same kind of knobs as your stove. That the bed I sleep in is similar to the bed... I mean, we have so much in common, and yet because of the natural sense that we have to hate each other, we have to keep telling people to love one another.

ET: Well said. Well said. Pastor Emeritus Davis, you've been in Georgia, in divided Georgia, segregated Georgia, you've come to Utah, you've experienced different things in Utah, discrimination. I recall a story about BYU, for example.

How have you stayed grounded personally?

RD: That's a great question. I have been in... I have lived in all of the states except four. Except four states in my short, lifespan, all the states except four. And I believe that the way African Americans are treated and responded to here in Utah is much worse than any other place that I've been. And in fact, my wife and I made the decision to stay here so that we could bring about some changes, some legal changes, change the laws, and get fair housing available to everybody, change the economic makeup. There were four African-American school teachers here when I came, now there are more than 50. And there was a Black superintendent of schools until recently. So we've made lots of changes and we need to make more of those. Politically, we still have so few African Americans that are elected to political office. One in the state legislature, Sandra Hollands. Why just one? Many of us go by the percentages and we say one would be equal to the 2% of the state's population, and maybe so, but maybe that's a place that we ought to go beyond the percentages of the state's population in terms of getting representation.

ET: Any other questions from the audience?

Carson: Hi, Reverend Davis. My name is Carson. I work here at the library in the human resources department. Just going based off what you said earlier about how hate is so natural, and maybe love is a little bit more hard work, and you've done a lot of hard work in your life, especially meeting so much hatred with love, what keeps you going?

How do you pull upon so much love in your life when you're met with so much hatred and hard work?

RD: My parents were lovers, they not only loved each other, but they taught their nine children to love rather than hate. And so we learned early on to put up with, to deal with, to get along with people who are of different backgrounds than us. And we learned that in such a way, we learned it spiritually. We learned spiritually that vengeance belongs to God and that it didn't belong to any of us. And so, we practice love as opposed to hatred, as opposed to the natural sort of reaction, we practice that.

Speaker 7: I had a question about, the people in this room are often the people who are either, I like to call champions or they wanna be allies and things like that, which is great. We can always all get more educated, learn more, challenge ourselves, etcetera. How do we, or any suggestions that you have to reach the people who I tend to say politely are more than naysayers, that they really aren't really wanting to be in the boat or fueling hate or things like that. How would you say... What would be a suggestion to reach them?

RD: First of all, I want to clearly say that I agree with you, that the people in this room are people who would normally be expected to and would likely respond positively. Mark Matheson's over here, and Betty's over there. And there are a number of others whose names I could call that would be natural in terms of showing love. So, how do you deal with the others who are not? Well, first of all, you gotta find them. And they are not always obviously present. Sometimes they hide behind... Well, they hide, and so, you gotta find them first. And then secondly, you have to make this special effort and I'm tired just from thinking about all of the stuff that I was asked to do here on this campus, for example. I'm tired just thinking about that. It makes my back hurt worse than picking cotton.

RD: But I'm tired of that. But still, although tired, you still have to continue to go out and find people. As I did with the state legislators. I went and knocked on their doors. I went to their businesses, I met them, I called them Mr. And all sorts of good things, so that I could get in the door and then I could share with them what I needed to share. And so, first of all, you gotta find them. Secondly, you have to go where they are. You have to go where people are in order to help them to change to what they need to change to.

ET: Dr. Bill.

Bill: Morning, Reverend Davis. You've been a professor here on campus. And so what can the University of Utah do to get more love here on campus? There's a lot of, there are a lot of incidents that happen that we don't know about but they're happening all the time, in the classrooms and/or just in the environment. What can the University of Utah do to, one, increase the number of underrepresented students? And could you tell us a little bit about your experiences in the classroom while you were teaching here?

RD: What does the university, what can the university do? What does the university need to do? One of the things is we need to go beyond the athletic arena in our recruiting. We do much of our recruiting, for this university at least, of African-Americans because they are good ball players or they are graduate students, but we don't do much to recruit the local people who live here in town, who have graduated from west and east and other high schools that are African-Americans. So I think one of the things to do is to go beyond the athletic arena in terms of recruiting. When I came to this university, there were less than 200 African Americans. Around 500, but total number of students would be what? 35,000? 35,000 students and yet only 500 of them would be of an African-American heritage and background. So, I think that that's another area is to recruit them in areas other than athletics and graduate students. I was recruited as a graduate student, and many of you came here as graduate students. But how many of you grew up in this community, African American and went to school here and learned about that? Secondly, I think that the university, the present president has a new policy that is more interested in finding people of different backgrounds and bringing them to the university. And I think that that policy needs to be passed on to the deans, and the professors and more of the people that are on the lower levels. Now, let me turn to some of my experiences. When I came here, one of the very first experiences that I had as in the classroom was from a fellow professor who said that I have to make sure that these students pass. And what he was saying to me was that I had an obligation to let African-American students pass because they were good athletes. And I said to him, "Clearly, if he does not do the work in my classroom and doesn't come to class then... " Well, anyway.

[laughter]

RD: So, I think we have to stop just passing people because they are of a particular hue, or a particular athletic background or so forth at the university.

ET: I wanna piggyback on, that's a great question that you asked Dr. Bill. Pastor Davis was my first Black teacher in the state of Utah. I grew up here, and I went to Layton High, but it wasn't until college where I had my first Black teacher. And I'll never forget it 'cause he taught Black history, and Black studies. And it's a situation where one of his assignments was for the class to go to a Black church. And for me it was like, "Oh, I always go to a Black church, it's not a big deal."

[laughter]

ET: "Not a big thing." But what happened was, we got into his church, we went to Calvary Baptist Church. And what happened was, these other students never saw that experience. And so, now they're starting to ask questions, and they're starting to learn and see something different that they perhaps never have. And so, there's a method to what he's trying to do and accomplish. So, we thank you Pastor Davis.

RD: And one of the comments that was regularly heard by me was that our churches are not reverent because they're noisy and loud, and clap their hands and pat their feet, and all of those sorts of things. And that they are not reverent and that they are not... Well, let's just deal with that. But I suggest to them that reverence is a different thing for different people. That what's reverent for one person, quietness and sitting down with your hands folded, and never saying Amen or right on or any of those sort of phrases is not necessarily an indication of irreverence, but rather a response to the God that we serve. So, I insisted that my students go to an African-American church, while they were student here on campus. And I'd probably get in trouble today with the Supreme Court the way it is if I did that today but...

[laughter]

Erie Dakonda: Hello, my name is Erie Dakonda, and I am a third-year student double majoring in political science and gender studies. I have a question of how one stays motivated when they feel unheard. Because I know my brother, he's an eighth-grade student. He came home and he's like, "My teacher said the N word teaching history." And I told her, "You can't say that." And when he went to go talk to the school, they're like, "Oh, for educational purposes, it's okay. But you guys can't say the N word." And my brother's like, "Well, no, it's derogatory. You can't say that." So, how does one feel like stay motivated when they feel like they're unheard?

RD: Well, let me just say that loudly and clearly that I believe that there is no place when the N word is appropriately used. Whether it's in the classroom, whether it's textbooks.

[applause]

RD: But I believe that you ought not... That you ought to find another way to say what it is that you have to say. Now, how does the students stay motivated? First of all, you have to know who you are. The guy that hired me when I first came, he got fired at the end of the second year I was here because he couldn't make tenure and I stayed until 2014. From 1970 until 2014. Well, that's a few more years than he had stayed. But there are his notion was that somehow I was in the position that I was in because of my skin color, but I was not there because of skin color. I was there because I knew the subject matter and I could handle whatever was being thrown at me. And so I think that's the other thing is you have to know who you are yourself, and you have to be able to say it. I think once you say it to your professors, that it is inappropriate to use that kind of language or that kind of book. I think you've... Then move on and do your thing to show that the word, the N word is not an appropriate word to use.

ET: Great question. We have got one more in the back.

James: You mentioned that you came here and stayed because you wanted to make some changes. There's other organizations here that are trying to make some changes. There's universities and companies that are trying to recruit diversity. But from the other spectrum, what can we share or say to students of color or professionals of color, why they should stay in Utah?

RD: Good, great question. When I first came to Utah, it seemed to me, and I don't know that this was true, but it seemed to me that all of the African-Americans that were graduating from the university were leaving on the first train that came by, or the first plane, or the first boulder, whatever, but they were leaving almost immediately. And so I think that unless we can find ways of engaging people in every aspect of the community, we will not be able to keep them here. There are people who are qualified, and yet there are people who say to me, "Well, I can't find any blacks who can do this, who can do that." Well, you haven't looked evidently if you can't find any because there are some people that are around who are able to do everything that you can do.

RD: And so I think that the Chamber of Commerce, the Black Chamber of Commerce and other organizations have to be able to facilitate an opportunity for a full participation in the community for everybody. And I think the last thing is, or maybe not the last, but at least the last that I wanna mention is that we also have to pay people for the work that they do. The labor of black people is not any less valuable than the labor is of any other person who does the same kind of work. So we have to pay people a livable wage so that they can then be able to survive as well as their peers. Mark, you were gonna say something.

Mark: Well, I just wanna thank you so much for being here with us, Pastor Davis. And you have mentioned that your time at the university has not always been without challenges. And I just want you to know that, when we brought Congressman Lewis here in 2015, and you and your community at Calvary and the Broader Wasatch Front Community, that was an extraordinary time. And it's great to hear about your teaching in the classroom for which you won awards. Eddy, if I may, thank you for sharing that. And I'm just very grateful to you for what you've done for the University of Utah. And I wanna thank Emma Houston, who is currently working as a colleague of ours here at the University of Utah. And you undoubtedly know, Reverend Davis, that Emma recently won The Human Rights Day award from Salt Lake City, The Human Rights Commission and the Mayor's Office in Salt Lake City. Emma, I'm just so grateful that you received that recognition and grateful for what you do for this institution every single day.

[applause]

Mark: So in addition to my heartfelt thanks, I just wanted to ask you about what was the last stage, I guess, in Dr. King's work, which was The Poor People's Campaign. And we know that Reverend William Barber is carrying on with his colleagues in trying to bring people of all races together who are impoverished to work for change politically and economically. And it strikes me as so fundamentally important if we're gonna keep the boat afloat. And I just wanted to get your responses to Dr. King's idea, and Reverend Barber's continuation of his work and the work of others in that particular project.

RD: Well, I'm convinced that as long as the larger community saw Dr. Martin Luther King's work as African-American work on behalf of black people, they were okay with it. But once he stepped beyond that and started talking about the Vietnam war, started talking about poor people, started talking about people in general, then those were the last days of his major work, but I think that's such a critical work that all of us have to do it and do it together. We have to put our shoulders against the wheels and push in order to make sure that everybody is treated the same way and that our community get the same benefits as everybody else does. Other questions?

ET: We're running short of time. So any other questions?

Speaker 12: So we've been talking a lot about bringing and recruiting people here. So my question kinda goes with that, I had a really good friend who, she was recruited by a company here in Utah, and she was Black, and she came and all of her friends said, "Why in the world are you coming to Utah? Do you know how they treat us?" And she's like, "It cannot be that bad." That's literally what she told all her friends, it cannot be that bad. She came here, she lasted six months, she was treated so badly and it made me cry. I witnessed it, I tried to help as much as I could, and I was like we can try to move... She lived in a different county than here in Salt Lake. And I was like, "Let's find you an apartment in Salt Lake," and we really tried everything that we possibly could, but she was just treated so badly that she literally quit with just her savings packed up and moved back to Texas. Because she was treated so horribly. And now she has that bad taste in her mouth.

Speaker 12: And so even when she has to travel here for business, she doesn't want to come. And that's the kind of perception. So when we are recruiting, when we are trying to get actively to get more diversity here in Utah, how do we change that perception of Utah? Because it's already out there. So how can we change that perception of our community and our state, to be able to retrain people? 'Cause some people don't know, like she thought it was gonna be a great experience and it ended up not being so.

RD: How to change that perception is much more than I know how to do. I've been trying to change the perception since 1970 and I still get, when I go to New York, when I go to Washington DC, when I go to Florida, I still get people ask me, "You live where?"

[laughter]

RD: And they want to know am I a part of the dominant religious group. And there are all sorts of questions that they ask. So how to change that, I don't know how to do that. But I think that one part of it is for people like myself and Emma Houston and Dr. Moses and France Davis II and the Eddy Thompson and James Jackson and others to stay here and to then go out and say Utah is not necessarily a bad place. You can make it what you want it to be. Dr. Bill back there was, I believe you were born here, right, Dr. Bill? Was born here in the area. And so he's been able to make this community his community by living here and staying. And I think that that's the only hope that I can give. When the hierarchy says this is what we are going to do and this is the way we are going to treat people who are different than us, then the lower people need also to understand that and to learn how to do that as well.

RD: Some years ago, my daughter was on her way from school in our community and was told by the neighbors that she couldn't walk on a certain side of the street. Well, there's something wrong with that, that any other child could walk on either side of the street, but for my daughter to be told that she couldn't walk on a certain side of the street.

ET: I think you make a good point there. For some, several of us that have grown up here, that are raised here, some that even come to the state on different accords for the college and things of that nature. It feels like we try to make it a mission, kind of like what you said, to make Utah great, to make this community, this beloved community a better place. And I think, one of the themes from yesterday was we need each other.

We need each other to stand up. We need each other to be advocates. We need each other to be allies. We need to speak up in the face of racism. When we see things wrong, we gotta speak up. We gotta say something, we gotta support.

How important it is to teach our children and all the educational institutions about human rights and accountability?

RD: It's essential that we teach human rights to all people that all people because they are human. Dr. King said it this way that hatred in one place is hatred in every place. And so it's important that we teach people that they respect, appreciate, and celebrate with others their differences. Those differences are like the smorgasbord restaurant. You go to the smorgasbord, you go to Chuck-A-Rama, and you don't eat everything that Chuck-A-Rama has.

[laughter]

ET: But it's an option.

RD: You pick certain things in Chuck-A-Rama and you eat those. And because of that, other people are then able to pick certain other things and who use those. So I think, it's important that we teach human rights, that we teach people to love and appreciate one another, and that all of us become a part of the beloved community. All of us become a part of the beloved community. And that's whether we are Black, whether we are Brown, whether we are Red, or whether we are White, we still have to become a part of the community. Thank you all for listening. And I believe there is...

[applause]

Speaker 14: Thank you so much, Reverend Davis and Eddy Thompson, for being here today and Allyson for moderating. So we planned box lunches for 50 people. So we do have those on your way out. Feel free to take a box lunch, first come, first serve, if you will. And, I'd like to ask our Marriott staff to abstain and let our guests get lunch first. So once again, another round of applause for...

[applause]

AM: And also, please sit around, check out books and items from France Davis papers, and explore the collection. Thank you so much for joining us today.

RD: And remember, we still have a lot to get done.

France A. Davis

J. Willard Marriott Library

Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Rising racist aggressions against the backdrop of an anxious and unnerving year can exacerbate the trauma racial groups and minorities experience. Megan Call of the Resiliency Center, social worker Jean Whitlock and EDI expert Mauricio Laguan explain racial trauma and how kindness, to ourselves and each other, is what this moment demands.

Well-being specialist Trinh Mai started BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of color) Check-in & Support via Zoom as a place to grieve and honor George Floyd and process ongoing racism. This is a space for employees at the U who self-identify as BIPOC to experience community, share struggles and solutions, and celebrate being who they are. Trinh and some members of the check in group share how the group started, how it has evolved and its lasting impacts.

Join the University of Utah community as we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and legacy. Here are suggested readings, resources, events and conversations throughout the week that honor Dr. King’s vision, offer direction, and challenge us to determine a better way forward.