Learning Objectives

After completing the lesson you will be able to:

1) Define the “flipped classroom” educational approach

2) Relay the pros and cons of this teaching method

3) Outline a plan for learner pre-work and in-class learning activities

4) Apply the “flipped classroom” method in health care and professional settings

Case Studies

Jamar doesn’t want to be boring.

Jamar is a general surgeon preparing for a lecture that he has given to residents year after year. An expert in the area of minimally invasive surgery, he is tasked with giving the surgical residents an overview of this topic during their lecture series. In reviewing last year’s feedback, learners felt overwhelmed by the number of slides covering background information and that they would have appreciated more discussion on surgical techniques and patient cases. One learner even felt that the session was, “boring and covered too much content in one hour.”

Sarah needs an engaged team.

Sarah is a clinical staff educator in the Emergency Department charged with implementing the fifth protocol change for COVID-19 swabbing this week. Her already exhausted staff are frustrated by the constant change and ongoing uncertainty. She sits down to send another stock email with the updated protocol, thinking: “There’s got to be a better way.”

hat if instructional time was spent achieving more sophisticated learning objectives? What if learners came to the classroom—or meeting or bedside—having already achieved the most basic levels of learning and could then focus on building upon that foundation? That is precisely what the “flipped” classroom aims to do.

Why instruction has to change

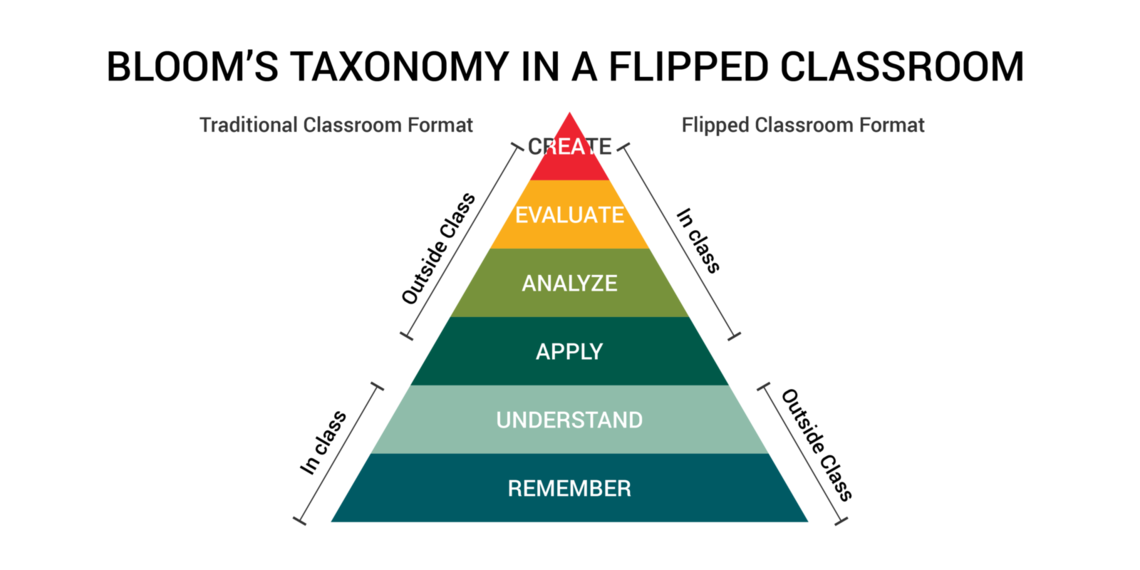

Historically, classroom teaching has involved delivery of content in a traditional lecture format followed by a homework assignment in which the learners apply what they have learned. In the professional medical setting, this model extends to our traditional thought leader forums, such as Grand Rounds and many didactic continuing medical education methods.

This educational approach involves little interaction between the educator and learners and leaves students to figure out the deeper meaning of what they have learned on their own after class. For practicing clinicians, this model must compete with busy schedules, entrenched processes and existing behaviors that often circumvent application of new concepts.

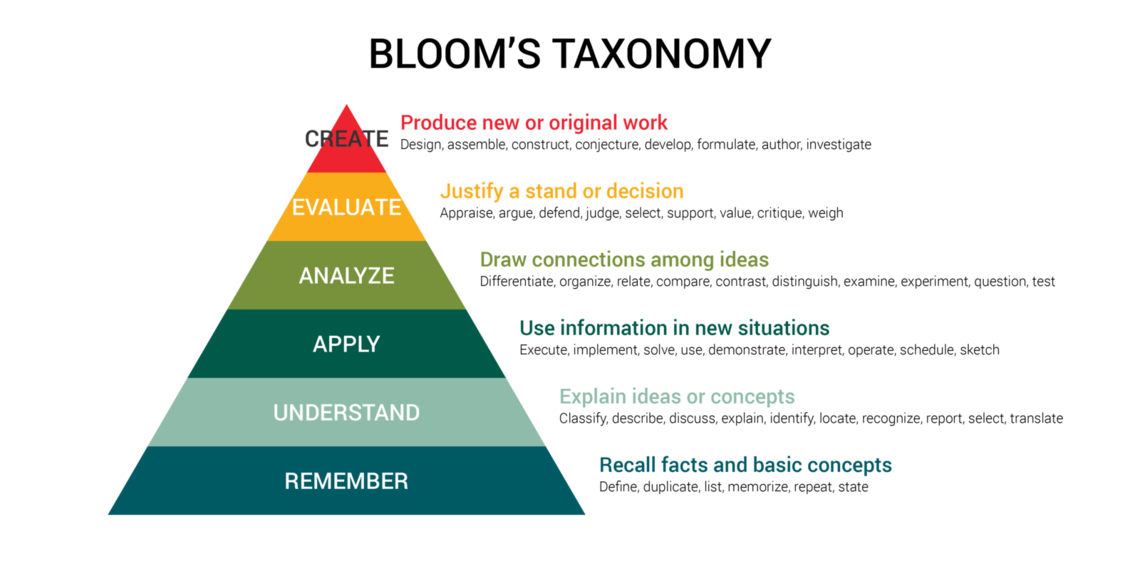

In education, there is a well-known hierarchy of learning objectives outlined by Benjamin Bloom.

In the revised version shown here, the most basic levels of learning involve the ability to remember facts and understand concepts. Moving higher up the pyramid, you can find higher levels of learning such as being able to apply and analyze what you have learned. In traditional lectures and meetings, instructional time is typically spent at the lower levels. The flipped classroom blends pre-work and classroom time to achieve a meaningful learning experience.

What is the “flipped classroom?”

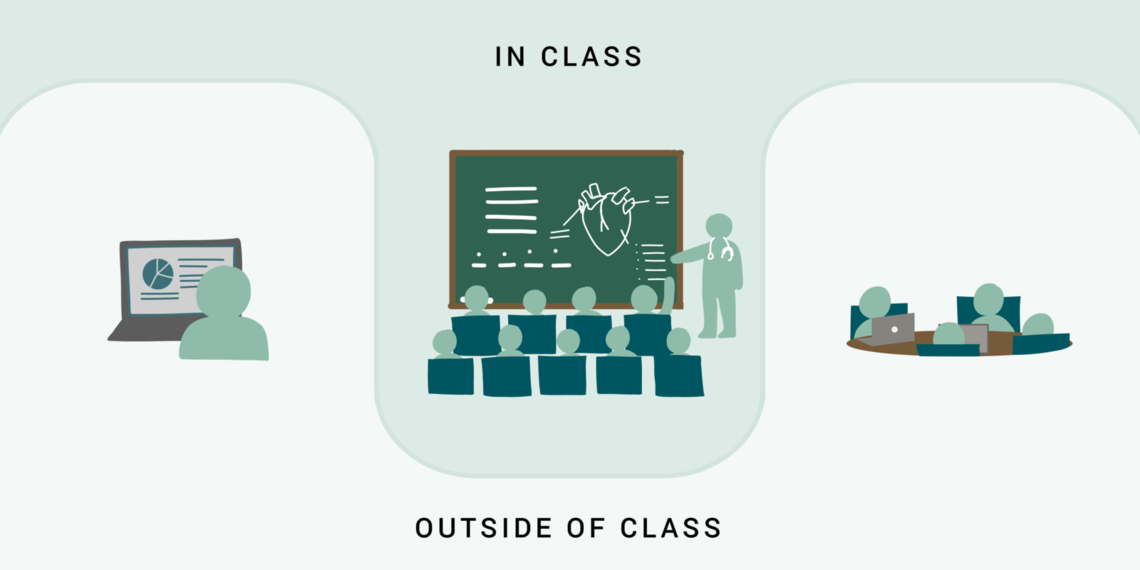

The “flipped classroom” is an instructional approach that has long been in existence, but is gaining momentum as more educators are becoming comfortable with technological advances. In this blended learning modelBlended learning integrates independent, often online methods of learning with supervised and collaborative approaches. learners are tasked with performing “pre-work” before their classroom time with the educator. Then, “live instruction” time is spent on the application of what they have previously learned. Active learning and engagement with the material that normally would have occurred as homework after class, has been “flipped” to now be an in-class activity.

In the professional setting, “flipped meetings” employ the same methods: providing “pre-work” via email or other modality that imparts greater context, can reduce meeting length and add depth to “live instruction” or team discussion.

What does it look like?

Here are some examples of pre-work and live instruction activities:

| Pre-work | In-class |

|---|---|

|

|

How do I do it? (Easy to use resources)

Here is some technology available to support the flipped instruction:

| Technology* | Resources | Learn more |

|---|---|---|

| Video (externally produced content) | Edutopia explains how video can amplify learning | |

| Presentation software |

|

There are many presentation software alternatives to explore |

| Screencasting software (screen recording) |

|

TechSmith provides The Ultimate Guide to screencasting |

| Learning Management System (LMS) |

|

U of U Teaching and Learning Technologies boasts a wealth of resources to get you started |

| Webcast and social software |

|

U of U Remote Resources Guide provides a list of training and tools available to faculty, staff and students |

| Other content delivery applications |

|

Both Marriott Library and Eccles Health Sciences Library offer expanded resources and support services for faculty and staff |

| Quiz and polling software |

|

Here are a few tips for writing better eLearning quiz questions |

| Website development | Custom student and instructor-generated websites such as Adobe Express and Wix provide visually stunning website templates | Learning portfolios are assessment and reflection tools that comprehensively illustrate what has been learned |

* Adapted from Moffett J. Twelve Tips for “flipping” the classroom. Medical Teacher. 2015;37:331-336.

Before you begin, consider the pros and cons

There are advantages and disadvantages to consider when deciding if this is the best modality for your next teaching session. It is also important to remember that a curriculum does not have to flip 100%. For example, some sessions or lectures may be best in a traditional format whereas others are more conducive to trying “flipped” classroom.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

The “flipped” classroom can work well in small or large groups and can be as high or low-tech as the educator is comfortable with. The main purpose is for the learner to be given the tools to prepare for a more interactive and engaging in-class experience that pushes their level of understanding. With deeper understanding of content, the hope is that their future patients will be better cared for.

Conclusion

Let’s return to our introduction case studies to see how Jamar and Sarah apply the flipped classroom technique.

Jamar’s teaching isn’t boring anymore.

Jamar uses the “flipped” classroom to restructure his previous teaching session on minimally invasive surgery. The week before his session, he sends out “pre-work” to learners which includes an article to read and a 20-minute video where he presents and discusses some of the background slides from his lecture last year. For the classroom time, he creates four cases based on real patients who had minimally invasive surgery. He develops a question guide for each case that encourages learners to decide how they would evaluate each patient, what intraoperative approaches would be best, and what to look for in the post-operative setting. Learners work in teams to answer the questions, while Jamar and the chief residents walk around to answer questions. For each case, he has video clips from the surgery that demonstrate key surgical techniques. After the group work, Jamar shows these video clips and goes through the answers to the questions. He receives excellent feedback for this session and learners appreciated the opportunity to ask questions and discuss real clinical scenarios.

Sarah has an actively learning and engaged team.

In some ways, the COVID-19 uncertainty has made staff more eager to learn. They are receptive to new information because they realize just how important it is. Sarah uses the “flipped” classroom approach by starting with why—she sends a meeting invitation that clearly and succinctly explains the rationale for the protocol change and provides a step-by-step visual 1-page visual summary of how to implement the protocol to be reviewed in advance. During staff meeting, she demonstrates the new procedure and allows staff to observe until they feel comfortable enough to try it. She leaves time for and encourages team discussion about the new procedure. In the following days she rounds on staff to check-in, identify concerns and answer questions, always making sure to validate emotions and concerns. Sarah will use their feedback to improve her method of instruction—she knows the protocol will change yet again.

References

-

A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education (Med Educ. 2017) Chen, Lui, and Martinelli review 118 studies and find the flipped classroom a promising teaching approach for increasing learner motivation and engagement.

-

Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom (Med Teach. 2015) Jennifer Moffett provides practical tips for applying flipped classroom method, and finds increased educator-student interaction.

Kathleen Timme

Keeping learners engaged during a talk or presentation is a challenge almost all educators have encountered. With the transition to more virtual learning over the past year, capturing learners’ attention can sometimes feel like an uphill battle. What are some tools and techniques to improve learner engagement?

Frequent and deliberate practice is critical to attaining procedural competency. Cheryl Yang, pediatric emergency medicine fellow, shares a framework for providing trainees with opportunities to learn, practice, and maintain procedural skills, while ensuring high standards for patient safety.

Effective Communicator: Redux. Communication lessons for the here and now, from setting boundaries to running a meeting.